Is Antonin Scalia’s originalism—indeed, constitutional self-government itself—passé? The eternal temptation to read one’s own values into the Constitution beguiles even religious conservatives espousing natural law.

The U.S. Constitution is the “supreme law of the land,” whose ultimate interpretation is entrusted, by longstanding custom if not by explicit textual direction, to the U.S. Supreme Court. Accordingly, it is vitally important to divine the true meaning of our fundamental law. When a state or federal law is alleged to conflict with the Constitution, how are courts supposed to resolve the conflict? How can citizens satisfy themselves that the black-robed oracles who interpret the Constitution are doing so accurately?

These questions are more pressing than ever, as contested issues of public policy increasingly end up in court to be decided as cases involving constitutional law. Since the heyday of the Warren Court in the 1960s, federal judges have asserted primacy over fundamental aspects of our lives, ruling on issues such as abortion, marriage, immigration, voting, education, pornography and obscenity, law enforcement, capital punishment, welfare benefits, racial preferences, religious expression, and the power of administrative agencies.

Legal scholar Lino Graglia, who taught for more than 50 years at the University of Texas School of Law, argues that a clique of life-tenured judges—a “tiny judicial oligarchy”—has usurped “our most essential right, the right of self-government,” by formulating a body of constitutional law that “has very little to do with the Constitution.” Graglia contends that many judicial decisions amount to no more than “the policy preferences of a majority of the Court’s nine justices.” In short, judges have improperly arrogated power to themselves by departing from the Constitution’s text.

In response to the activism of the Warren Court (and the marginally better record of the subsequent Burger Court), conservatives in the 1970s, led by Robert Bork, advocated a jurisprudence of “original intent”—hewing to the original meaning of the Constitution, based on its text and history. Following decades of heedless activism, this was a bold position. In a 1982 article in National Review, Bork famously stated that “The truth is that the judge who looks outside the Constitution always looks inside himself and nowhere else.” Like the boy who pointed out that the emperor was naked, Bork’s critique was devastating.

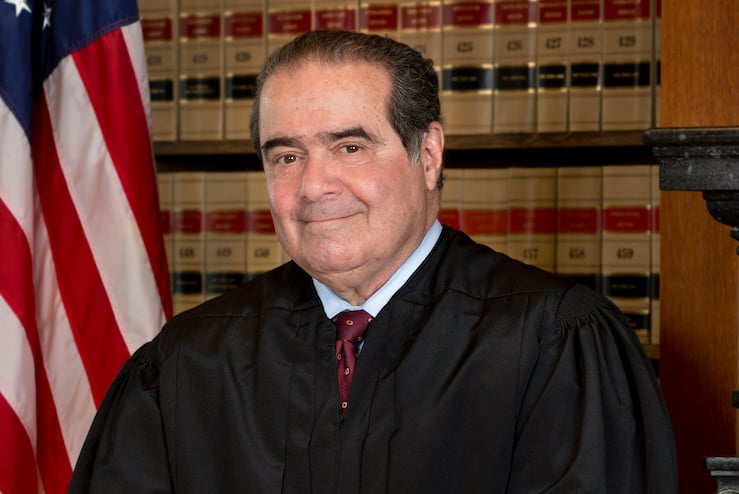

Famed jurist Antonin Scalia and others tweaked “original intent”—which focused on the subjective intentions of individual Framers—into a more general inquiry into the original public meaning of the constitutional provisions when they were enacted and ratified. How were the words understood at the time they were adopted? This is the central doctrinal question of constitutional originalism.

Originalism, now accepted—albeit with many variations—as an influential theory of constitutional interpretation, served as a check on fanciful theories advanced by liberal scholars and jurists, who regard the Constitution as a “living” document that can (and should) be adapted to suit the evolving needs of society. Taking seriously the original public meaning of the Constitution constrains extra-textual flights of fancy, such as the “penumbras, formed by emanations” that animated the activist decision in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965). That decision recognized a “right of marital privacy” that precludes state regulation of contraception.

Griswold’s discovery of an implicit constitutional right paved the way to the invention of abortion rights in Roe v. Wade (1973), the right to engage in homosexual sodomy in Lawrence v. Texas (2003), and, ultimately, the right to same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). The impact of originalism, although not sufficient to prevent Obergefell, produced a narrow 5-to-4 decision, unlike the lopsided 7-to-2 margins in Griswold and Roe. Conservatives console themselves with the hope that President Trump may eventually appoint an originalist majority to the Supreme Court; Trump’s excellent picks, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, join Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas to form a solid originalist bloc. One more solid Trump appointment could be decisive.

Non-originalist theories are not limited to the political left. On the right, some conservatives and libertarians have espoused constitutional law theories derived from certain interpretations of natural law, the principles of the Declaration of Independence, and other extra-textual sources. This group includes Hadley Arkes (Amherst), Richard Epstein (Chicago, NYU), Randy Barnett (Georgetown), and the late Harry Jaffa (Claremont), although some claim to be originalists and even risibly argue that judicial restraint is a variant of the “living” Constitution.

The motivation of such “conservative constitutional revisionists” (as Bork described them in his 1990 opus, The Tempting of America), is the same as their counterparts on the left. If they can conveniently find their policy preferences embodied in the Constitution, the attainment of their goals rests only on mustering five votes on the Supreme Court, rather than in electing, persuading, and maintaining a majority of sympathetic legislators at the state or federal level.

The allure of such constitutional fantasies is heightened by the reality that politics is often a fickle tool for achieving desired policy results. Bork called this allure a temptation to substitute personal predilections for legitimate constitutional interpretation, and noted that succumbing to it ineluctably turns a judge into a legislator.

In the originalist view, the Constitution puts certain things off-limits to political majorities, either expressly in the text or implicitly in the constitutional structure, such as federalism or the separation of powers. A principled originalist judge will enforce the Constitution as written, but otherwise will not override the political branches merely because he disagrees with the policy outcome.

As Bork explained, “in wide areas of life majorities are entitled to rule, if they wish, simply because they are majorities.” Adhering to the Constitution as written, a principled judge will defer to the political branches, absent an express constitutional provision proscribing majority rule.

Bork and Scalia both emphatically rejected the notion that unwritten principles of natural law lurked invisibly in the Constitution, warranting the judicial invalidation of state or federal laws that did not otherwise contravene an enumerated constitutional right. Bork archly remarked that “Judges, like the rest of us, are apt to confuse their strongly held beliefs with the order of nature.” Scalia scoffed at the idea that the Constitution—which he termed “a practical and pragmatic charter of government”—contained enforceable “aspirations” or that abstract “philosophizing” was a substitute for concrete and specific textual commands.

During their lifetimes, Bork and Scalia were able to keep the revisionists at bay on both the left and the right. Alas, Bork died in 2012, and Scalia in 2016. Already the revisionists are dancing on their graves.

With the legal academy dominated by progressives, and the handful of center-right legal scholars consisting mainly of libertarians, the Bork/Scalia conception of originalism is being seriously challenged. Judicial restraint is in decline, and various formulations of “judicial engagement” are ascendant in academic circles.

On the right, some theorists advance natural law arguments that would superimpose their policy preferences onto the Constitution, sans text. In many cases, those policy preferences—e.g., opposing abortion, supporting traditional marriage, promoting the family, protecting property rights and economic liberties—are legitimate conservative goals, but constitutional government dictates that public policy be enacted through the political process, not by judicial edict.

A notable exemplar of the natural law theorists is Gerard V. Bradley, a respected law professor at Notre Dame, whose recent essay in Public Discourse, “Moral Truth and Constitutional Conservatism,” argues against the ethos of much of the Supreme Court’s abortion jurisprudence. That ethos is epitomized by the widely ridiculed “Mystery Passage” penned by Anthony Kennedy in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), which states, “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.”

Reacting against such secular nihilism, Bradley argues that judges must rely upon “moral and metaphysical truths that lie beyond the Constitution” in order to interpret the Constitution. What are these unwritten “truths”? They are truths that answer such “foundational questions as, [W]hen do persons begin? Which propositions about divine matters are answerable by use of unaided human reason, and which require access to revelation?”

Bradley unconvincingly calls his approach “originalism,” but it sounds suspiciously like Rawlsian moral philosophy masquerading as constitutional theory, the kind of thing that was commonplace on the left in the 1970s. Bradley declares that “today’s conservative constitutionalism is inadequate…” to turn the tide against the vortex of activism evidenced in Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

Given the state of “breathtaking subjectivism” evident in decisions from Casey to Obergefell, Bradley charges that judges cannot return to a neutral role as umpires, merely calling balls and strikes: “For decades…constitutional conservatives have diluted [constitutional interpretation] with a methodology of restraint, a normative approach to the judicial task marked by an overriding aversion to critical moral reasoning.” Returning to a neutral role would be, Bradley says,“philosophical abstinence.”

Accordingly, judges should rule based on their own moral reasoning. Deferring to political majorities is, in Bradley’s view, inadequate because “We have passed a tipping point where damage control amounts to no more than a slow-walking surrender.” Moreover, in view of “the collapse of public morality…in our law and culture,” we can no longer count on political majorities to make morally reliable choices. In short, a debauched and godless population is “incapable of wresting control of the law back from the regime-changing project of autonomous self-definition.”

The implication is that conservative judges, instead of simply overruling Roe v. Wade and leaving the regulation of abortion to the states, should ban the practice altogether on moral grounds; instead of overruling Obergefell and leaving the definition of marriage to the states, judges should restrict the institution to one man and one woman, and so forth.

Bork’s response to judicial activism in aid of the culture war was to advocate limits on judicial review, so that political majorities could govern themselves without undue interference. In contrast, proponents of natural law and similar contrivances seek to expand the judicial role to allow appropriately enlightened mandarins (those on “our” team) to impose their agenda on the polity. This is not how a constitutional republic is supposed to work, and is not what the Founding Fathers intended. Bradley’s invitation for judges to “replace bad philosophy with good philosophy” finds no support in Federalist 78. Fidelity to the Constitution self-evidently cannot be achieved by looking “beyond the Constitution,” and it is absurd to call such an end-run “originalism.”

Legal academia has become such a theoretical fever swamp that even erstwhile conservatives have become advocates of the “living Constitution.” In The Political Constitution: The Case Against Judicial Supremacy (2019), political scientist Greg Weiner pushes back against the emerging center-right legal scholars advocating “judicial engagement”—a euphemism for empowering judges to negate popular self-government. Even a decade ago, such a book would not have been necessary, but the legacy of Bork and Scalia is unraveling before our eyes.

Weiner trains most of his fire on libertarians such as Timothy Sandefur, Clark Neily, and Randy Barnett, the go-to guru in Federalist Society circles. He also includes in his critique various conservatives espousing natural law, such as Hadley Arkes and Harry Jaffa. I will not belabor criticism of the ongoing project of Jaffa’s acolytes, sometimes referred to as “Claremonsters,” to override the Constitution with the Declaration of Independence. Suffice it to say that such a project is little more than an elitist maneuver to override not only the Constitution, but the will of the people, as well. By contrast, Weiner’s wide-ranging defense of the res publica—the political community as a whole—serves as a broadside against anti-majoritarian usurpation of democratic rule.

Is the Supreme Court’s constitutional jurisprudence an Augean stable badly in need of cleansing? Absolutely. Have activist decisions over the past 50 years done grave damage to American institutions? Without a doubt. The solution, however, lies in restoring the judiciary to its intended role as the “least dangerous” branch of government, not further eviscerating constitutional democracy by encouraging judges to impose their subjective moral judgments on political majorities without their consent.

Ordered liberty is to be found in the filtered political decisions of “We the People.” Majority rule is not tyrannical; minority rule would be. Consent of the governed is possible only through democratic institutions—the rough-and-tumble of representative government. These concepts are enshrined in the Constitution; natural law is not. The artifice of deciphering invisible ink in the Constitution—moral truths revealed to our robed masters in séance-like fashion—is a license for judicial activism. Disaffected conservatives tempted to surrender their sovereignty to federal judges would be well advised to read Weiner’s illuminating book, or to reread The Federalist Papers. Americans are capable of governing themselves quite well, if judges would only let them.

Leave a Reply