To understand contemporary Western culture and politics, I suggest a term for something that is as old as the experience of man, but which has never before settled into institutional permanence. I shall call it noise.

What do I mean by this? We must draw a fundamental distinction. Noise, as I use the term, is not sound, even when the sound is shrill, like the scraping of a chainsaw on the trunk of an oak, or loud, like the whoops of boys playing ball, or unsettling, like the groan of a sick man. Noise is what it is by interference, its power to tear thought and personality to shreds, to send genius off into centripetal irrelevance, to stifle calm deliberation, contemplation, and prayer.

Consider the following scene. The year is 1850, and we are in the Eagle Tavern, in Rochester, New York. Six Indian chiefs from the Tonawanda tribe, dressed in buckskin, have come to call upon a woman to sing to them. She is glad to do so. She has the fine yellow-white hair of the true Swede, arranged in braids that ring her head like a crown. Her eyes are a glittering blue, and her movements bespeak dignity, humility, and the great heart of someone who, as one of her admirers said, could forget herself in service of the divine. She sings them the folk songs of Sweden, and they leave her company, grateful and satisfied.

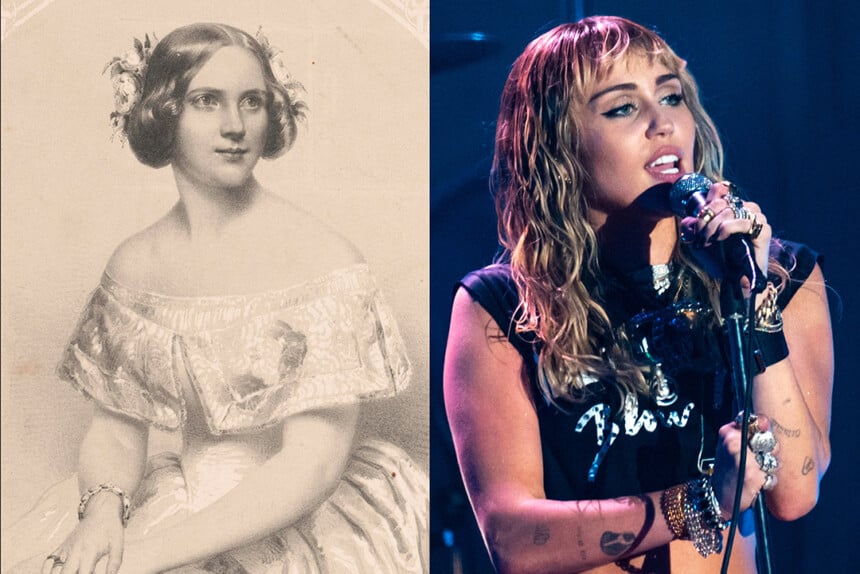

The singer was Jenny Lind, and in a tour of more than a year across the continent, she filled the concert halls of America with music, not with noise. For the latter, we might turn to P. T. Barnum, that uniquely American conglomerate of boyish adventurer, preacher, huckster, self-promoter, confidence man, and moral reformer, who blew a trumpet before his star singer, crying her up in one city after another, so that when she finally arrived in town, audiences lined up by the thousands. Barnum kept his share of the profits for himself, although he was also known for his public generosity; Jenny Lind used hers to endow free schools back in Sweden.

She seems to have been a profoundly good woman, nourished by wells of silence. Her dear friend, the composer Felix Mendelssohn, called her “a member of that church invisible.” Hans Christian Andersen said that it was Jenny Lind who first taught him “the holiness of art.” I read in The Century Magazine (the August 1897 issue, published many years after Lind’s death) that “her tour was the supreme moment in our national history when young America, ardent, enthusiastic, impressible, heard and knew its own capacity for musical feeling forever.” She sang the airs of the grand operas, especially those composed by her friend Giacomo Meyerbeer; she sang from the folk traditions that enriched the soil for such composers as Brahms and Dvořák; and, taught by Mendelssohn, she raised up the souls of her audience, when she performed in the oratorios, “into the sacred presence.”

“Jenny Lind’s impression upon her audience,” said the virtuoso violinist Henri Appy, “was the result of four remarkable qualities united in one artist—a voice unique in power, musical beauty, and dramatic quality; a thorough musicianship; unusual intellectual culture; and a character of unaffected goodness, kindness, and high moral principle, which gave her insight into a range of emotions, especially in religious music, possessed by herself alone.” In each of these qualities we can recognize both sound and silence, the silence of profound love, of calm and farseeing mind, and of humility before the divine. For music and silence are sisters, arm in arm, as the old liturgists in my church, the Roman Catholic, used to know.

Now think of Miley Cyrus, performing the halftime show at this year’s national basketball tournament. The huckster we will always have with us: this time he sells us slogans, “Equality” and “Unity,” painted upon the court, lest the basketball fans forget for a moment their political passions, and fall back into the simply human again. Miss Cyrus has no “intellectual culture,” and there is no virtuoso performance on a violin, or even a guitar or a banjo. The very lights around her shriek. You can turn off the sound, but not the noise. Her face seems to be twisted in madness and wrath; no smile but a petulant sneer; no blink of the eye to suggest a trace of the meek or kindly or self-effacing. You would not want to be imprisoned in that skin.

What does it mean to be a people whose Jenny Lind…is Miley Cyrus? I am not simply talking about moral corruption or a collapse of good taste. Those are common in the fall of many an empire and culture before ours. I mean that a certain organ of intellectual, moral, and aesthetic perception has been destroyed by the noise; and we are no longer aware of the destruction.

Of Jenny Lind, said Appy, “no one ever heard her sing ‘Home, Sweet Home’ without weeping.” I cannot imagine anyone now writing similar words about anyone singing anything: the habits of noise and responding to noise make it impossible. We lack the peace for it. We may lack the home for it. In the opera “La Sonnambula,” says Fanny Morris Smith in the same issue of The Century “her dignity and innocence convinced her listeners and brought them to tears.” What Miss Smith has in mind is the aria “Ah! Non credea mirarti,” wherein the soprano, Amina, the sleepwalker heroine of Bellini’s operetta, weeps for the love she has lost, as her fiancee Elvino, unaware of her affliction, believes she has been untrue when she is found at night in the room of another man. One must have a certain openness of soul, a quiet receptivity, to be moved to weep for her while she looks at the flowers of her bridal bouquet, d’etterno affetto tenero pegno, withered too soon, alas.

From here the student of noise, the kraugatologist, if I may coin the term from the Greek κραυγη, which means “outcry,” can take the discussion in a variety of directions. There is noise properly speaking: the decibels. Baseball was once the preeminent game for conversation. Its leisurely periods of calm, punctuated with intense drama, allowed for it. For baseball, like the other essentially American game of football, is a stop-and-start game, with each stop giving the players and the spectators the opportunity to think, to plan, to criticize, to chat about love or money or hunting or anything else in the world; and of the two, baseball is by far the more pastoral, played in the summer sunshine. But if you go to a ballpark now, you will have to shout to talk to your friend sitting next to you—forget about the stranger three seats away. The people in charge of the noise must believe that we all desire to be relieved of the leisure, the conversation, and the silences.

There are other noises of passion, especially the political. Every slogan is a political bullhorn, posing as speech and thought. We have always had such, but we also had the opportunity, even the necessity, of the quiet interlude, and the careful composition of arguments. No doubt passions were high when the confederated states of America were faced with a constitution to ratify, and I am sure that now and again an eye was blackened or a tooth broken. Madison and Hamilton did not mince words. But in The Federalist we find political analysis of the highest order, with appeals to history and life in Periclean Athens or the city republics of Renaissance Italy, and a shrewd appraisal, corroborated by experience, of the pride, the partiality, the stubbornness, and the folly of man.

above: title page of The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, as Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787 (1st ed.) printed and sold by J. and A. M’Lean (Library of Congress)

I might note here what has been noted before, that the broadsides once meant to be read by farmers, fishermen, and mill workers would now overtax the linguistic capacities of college students; but that is not exactly, or not alone, my point. I might note that college professors themselves cannot write as Madison did, because they lack the learning for it, not to mention the literary skill; that too is not quite it. The Federalist cannot be written now, because it cannot be thought, and it cannot be thought, because the noise trips up the first small steps of thought.

In Federalist 6, Hamilton, warning that men by nature “are ambitious, vindictive, and rapacious,” says that “to look for a continuation of harmony between a number of independent, unconnected sovereignties situated in the same neighborhood would be to disregard the uniform course of human events, and to set at defiance the accumulated experience of ages.” Put that statement before a couple of television personalities to discuss. They do not get so far as to debate how accurate Hamilton’s history is, though Athens and Thebes and Sparta, or Florence and Pisa, rise up to testify on his behalf. They do not know history. But suppose they did know it. The shrieks interfere. How dare we appeal to a common human nature? How dare we say such hurtful things? How vicious must be the man who says them! And why should we be bound by history? Is not history being made all the time? Aren’t we our own history? Hamilton must have been actuated by an evil motive—and such supposititious motives are easy to invent.

In Federalist 55, Madison considers what should be about the right number of men to represent the various states in the lower house of the proposed Congress. It is not possible, he suggests, to decide the issue by formula, for “sixty or seventy men may be more properly trusted with a given degree of power than six or seven,” but “it does not follow that six or seven hundred would be proportionately a better depositary.” As for six or seven thousand, “the whole reasoning ought to be reversed,” for then the body would be prey to confusion. “In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever characters composed, passion never fails to wrest the scepter from reason,” says he, concluding with this apt and devastating observation: “Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.”

Again we have a truth we are not permitted or enabled to conceive. The noise interferes: not just the noise of the de facto mob, busying themselves as self-appointed judges and juries over criminal cases a thousand miles away, or rallying for or against measures that neither they nor their nominal representatives have read, but the noise of that mob in the wreckage of the soul.

Why is it not the more the merrier? If 10 wise men are great, why not a hundred or a thousand? Why not a plebiscite of a hundred million voters? Equality, equality! And they who scribble upon the walls of a dilapidated culture, the journalists, the politicians, and those in the professoriate whose words are but counters in a raucous stock exchange of power, will fill the air with passionate vagaries, like “toxic masculinity” and “intersectionality” and “bodily autonomy” and “social justice,” terms that might have some residue of meaning, if they were sifted through careful and dispassionate analysis, but that are employed precisely to ensure that such analysis is never undertaken. I have chosen terms from the statist left, as they are the ones now drumming the loudest in our ears, but the phenomenon is endemic.

Passion where it does not belong, or where it is not kept under the strict rein of reason, is noise. The response to the viral pandemic last year provides a case in point. It is not that I believe that in general we took the wrong measures. I do not know. It is that we never even had a rational discussion of what the measures should be: lives were at stake, no one could know how many and whose, but so also was a way of life, and since nothing worthy to be called life can be free of danger, it was incumbent upon us to consider risks and losses in their wide and largely incommensurable variety, and to understand that whatever we did, we would suffer for it. We did not have that discussion because we could not have it: just as you cannot read a poem while a hundred voices are shouting at you. You can’t reason with Carrie Nation. But if your soul is full of Carrie Nation, you cannot reason with anyone at all.

I can say this at least about Mrs. Nation: brought up in a world formed by a masculine ethos, she took attacks on her person in stride. But when the political and the personal become indistinguishable not only in the occasional unfortunate fact but as the necessary result of false premises; or when people no longer perceive the difference between saying “You are wrong” and “You are wicked,” then rational discussion becomes inconceivable. Narcissism makes a lot of noise. It does so in a fraud of a language, as its sentimentality is the fraud of a feeling. A word like “sexism,” rather than denoting something clearly defined, such as an irrational hatred of or contempt for one sex or the other, is tossed like a torch into a barn. It is meant not to initiate but to frustrate discourse. You can defend yourself against an accusation, by analysis of the facts, or by discovering an error in reason. You cannot so defend yourself against a shriek; and soon enough you will be shrieking in turn. Our politics are a cacophony of shrieks.

In this respect, our schools are factories for political and counter-rational noise. Students learn how not to read. Again I am not talking about mere failures to attain some standard of quality. The schools do not fail. They succeed: they mean to convey and to magnify the noise. Suppose Shakespeare’s The Tempest is on the syllabus. It is a play of wonder. Even Caliban feels it, as he says to his drunken, noisy, and easily distracted companions:

Be not afeard: the isle is full of noises,

Sounds and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not.

Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments

Will hum about mine ears, and sometime voices

That, if I then had waked after long sleep,

Will make me sleep again; and then, in dreaming,

The clouds methought would open and show riches

Ready to drop upon me, that when I waked,

I cried to dream again.

If you do not have the music in your soul, if you are not responsive to beauty as even Caliban the thing of darkness is, then in a fundamental sense you cannot read this play. Rather than have the students pause, and consider, the teachers in our time do the easiest thing in the world, which is to drown the play in the noise of politics, jabbering about the natives in the new world (but the island is in the old Mediterranean), colonialism (but Prospero the wise magician wants to leave the island, go home, and never return), and sexual power plays (but a boy and girl, high-minded and sensitive to beauty, fall in love and try to outdo one another in humility and free giving). Why bother to read Shakespeare for this, and have barely literate students struggle with the early modern English? Will not the barely literary Margaret Atwood suffice?

The kraugatologist should ask whether Madison’s shrewd analysis of the relationship between the behavior of political assemblies and their numbers applies to other human endeavors. I am thinking here of the strange inverse ratio that often obtains when we find a place and a time of intense artistic or intellectual accomplishment. You are walking the streets of an Italian town or city, at any time in the 15th and 16th centuries. Chances are good that you will happen upon an artist who, if he were alive today, would be renowned throughout the world, but who at the time was just one among the crowd: a Lorenzo Lotto in Bergamo, a Pinturicchio in Perugia, a Mino da Giovanni in Fiesole. Yet the population of Italy then was a mere fraction of the population of, say, California now, not to mention the entire United States, or the world.

above: detail of Statue of the Prophet Habakkuk (a.k.a. Lo Zuccone), by Donatello, marble, 1423-1425 (Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence/ Wikimedia Commons)

It is true that the arts are not nearly so important to us as they were to the Florentines who gazed in wonder at Michelangelo’s “David,” or who took to their intelligent hearts Donatello’s bald and ugly Habakkuk, and called it lo Zuccone—the Pumpkinhead. Our geniuses do other things, we suppose; and that prompts the question, why so few of them do turn to the arts, and again we may come to the noise, the noise that stifles the turn toward beauty in the first place, in favor of the quick, the cheap, and the vain. Besides, in absolute numbers it may not be so: we may well have as many people in our vast nation who call themselves artists as Raphael had in his small nation. But where is our Raphael?

One may say that great art springs from the soil of religious devotion, so we expect a secular age to make more microwaves than Madonnas, but that too may be to argue in a circle, or assign as a cause what is but another form of the same effect. Are we a secular age because of clear thinking and conviction, or because of noise, so that we are what we are not by what we think, but by what we do not think—or by the fact that we don’t think at all?

Multitudes make for noise, and noise weighs heavy upon the soul. We need not retire from the world to be mostly free of it. Something about, let us say, Eton or Rugby, or the studio of Ghirlandaio, or the University of Paris in the time of Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure, was conducive to learning, to brilliant thought, and to the making of masterpieces, and such schools, studios, and universities were scattered like grain across the fields of Europe. Nor were such places islands unto themselves. But in important ways they were shielded from noise—from political passions, from the lure of the popular and demotic, and from incessant and thoughtless chatter.

Consider what it is to write in a strict meter, or to analyze the arguments of one article in a scholastic summa, or to chisel an arm that looks like an arm and not a rolling pin. Most of the noise then cannot get past the door. We do not have to argue about whether some litter of slogans is a good poem, when it clearly is no poem at all. We do not have to argue about whether the jargon-ridden maunderings of a Judith Butler are good English criticism, when they are not even good English prose. Why sweat and strain to fashion one small poem like a jewel, when the costume glass sells for a hundred times more? But you will lose your very sense of the jewel; your tastes will be debased; you have not the clarity and the calm of the mind to wait upon what is truly good.

Noise demands attention, attention distracts the mind. Noise makes for poor quality, and its ubiquity sets the standards. The numbers drag. Click, and you express an opinion; and the great sluggish swampland of opinion does its work. If your ears are full of Miley Cyrus, you will find it hard to listen to Jenny Lind; you will yawn, and your mind will wander. There may be exceptions, but widespread social phenomena are not governed by exceptions. If you go to church for the chatter, you will soon find silence unnerving, and you too will yawn as you pray. If your opinions are formed by the ephemera of social media, or by the political passions of a riot, or by the “theory” of the schools, you will not read The Federalist, even if you have the capacity to do so. You will not read my copies of The Century Magazine. They reward patience, but they are pitched for the sort of people who loved Jenny Lind, and we can hardly imagine what such people were like.

The Tonawanda chiefs were closer to the learned authors of The Century than we are. They may not have grown up with letters, but they did not have their minds stunted by noise.

Image Credit:

above left: Jenny Lind c. 1850 (Library of Congress) above right: Miley Cyrus in 2019 (Wikimedia Commons)

Leave a Reply