There was a very odd occurrence in the “Cradle of the Confederacy” in July 1987: Presidential aspirant and civil rights activist Jesse Jackson paid a visit to the Montgomery, Alabama, home of George Corley Wallace.

It had been 126 years since Jefferson Davis stood on the steps of the Alabama capitol and been sworn in as the president of the Confederate States of America. It had only been 24 years since Wallace himself stood in that same place and been sworn in as governor of Alabama. In his inaugural address, Wallace promised to:

sound the drum for freedom…and send our answer to the tyranny that clanks its chains upon the South. In the name of the greatest people that ever trod this earth, I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever!

So why would Jackson come to call and publicly ask for Wallace’s support? Jackson’s political ambition and the slow, yet dramatic shift Wallace had made in his racial rhetoric over the years hold the key to this mystery. But what motivated Wallace to change—or was his change even genuine?

There was much more to Wallace than segregation. His appeal became nationwide, and the issues he espoused had tremendous influence on both major political parties over the years. But he is primarily remembered as that black-and-white image standing in the schoolhouse door or as the candidate shaking his fist amid fiery oratory behind a podium. In spite of all the other issues and all his later efforts, Wallace remains a supreme symbol of hatred and bigotry to the public at large.

Wallace was that rare and true outlier candidate so seldom seen. He was bold enough to be unobligated to the special interests. Often underestimated, he communicated well and terrified the elites. He had such a deep and lasting effect that his ideas were co-opted by major players in both parties.

Officially, Wallace was a four-time governor of Alabama. But the reality was that he was a five-time governor, since Wallace ran his wife, a political novice, in 1966 when he could not persuade the state legislature to amend election laws prohibiting governors from serving successive terms. Lurleen Wallace became only the third female governor in American history with George as her “chief advisor.” Her husband took the title back four years later.

above: Newly elected Alabama Gov. Lurleen Wallace, right, is shown with her husband George C. Wallace in this Nov. 1966 photo. (AP Photo)

Wallace was not born into the ruling class. No silver spoon accompanied his humble, hardscrabble beginnings in the poverty of Barbour County, Alabama. Raised a proud Southerner, he said the two things that had the greatest impact on his life were Reconstruction and the Depression. As governor, he was criticized by outsiders for flying only the state and Confederate flags atop the capitol dome in Montgomery. Wallace was a World War II veteran, so he had an affinity for the Stars and Stripes. But he held that the flag of the general government had no business supplanting symbols of local authority and confusing issues of power at the very seat of state sovereignty.

Over the decades Wallace became the working-class voice of Alabamians. Then, with his presidential campaigns, he was the representative of the law-and-order “little man” across America. He kindled a sense of self-worth and dignity among the alienated and marginalized common man who had no voice in Washington. His were the original “Deplorables” and the Silent Majority before those names were coined. Over and over, Wallace endured the epithets still spewed at this group today.

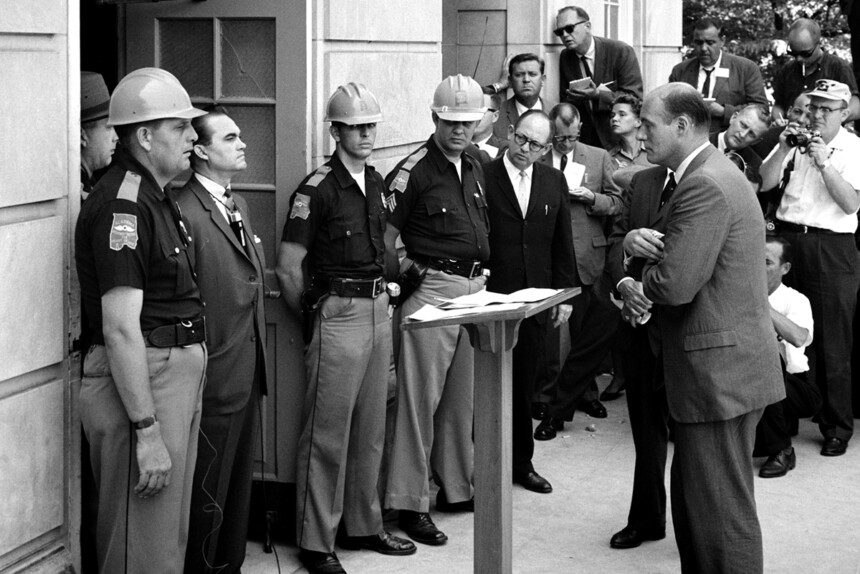

Yet in spite of this defense of the common man, Wallace is remembered most by the masses for his “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door” at the University of Alabama on June 11, 1963. Looking back at this showdown with the Kennedy administration over school integration, Wallace remained proud that he had orchestrated a high-profile method of articulating the constitutional issues at stake without the violence that accompanied Little Rock in 1957 and Ole Miss in 1962. Wallace was determined to be a public proxy. When his constituency and fringe supporters offered to stand with him, he kindly declined, explaining that he was instead going to stand for them.

In the poisonous political climate of the 21st century, it is nearly impossible to have rational conversations about the social issues of the 1950s and ’60s. Just as the myriad of complex disagreements that resulted in secession and the War Between the States is now hollowed to the singular issue of the abolition of chattel slavery, the issue of segregation 100 years later is reduced to the false narrative of the evil white man imposing his hatred of the black man through institutional racism. Nearly 60 years later, not only have the wheels not fallen off that bus, but the bus has become a revenge locomotive surging ahead with full steam.

Integration efforts were met with varying degrees of resistance throughout the South in the 1950s. What may be difficult for many today to understand is that this resistance was fueled by motives other than racial suspicion, although that too was undoubtedly present in the reaction to federal integration efforts. Many Southern whites feared this imposition would wreak havoc on their way of life and even private associations. Unfortunately, they were not wrong about where federal intervention would lead over the decades. Wallace, for better or worse, articulated these concerns and therefore gained the trust of Alabama voters.

Social motivations that drove Southerners of the Greatest Generation to support men like Wallace paralleled those provided by men like Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali. The latter two are seen by the left today as heroes. Their white counterparts are seen as devils.

Unlike those who today sanction violence and crime in the streets as a way of “making their voices heard,” the Christian, Southern men who Wallace attempted to represent were not driven by hatred, even though they were imperfect, flawed people. Their primary motivations seemed to be the embitterment they felt toward the federal government for continuing to exploit the race issue. They were also reacting to the hypocrisy of Northerners who were intent on imposing on the South through governmental force something they themselves refused to tolerate in their own neighborhoods and institutions.

Wallace would play on this inconsistency when he made his first run for president in the 1964 Democratic primaries against President Lyndon Johnson, carrying his populist message to the Northern primaries with surprising success.

One can study the texts of Wallace’s inaugural address and his schoolhouse-door speech from 1963 and see the consistent themes of federal overreach, State sovereignty, Yankee dissimulation, constitutionalism, free enterprise, and regional pride.

So Wallace made his fateful stand. He made his points vocally, and then the two black students who enrolled were eventually admitted into the university, backed by the armed might of the federal government. Virtually ignored in the popular history of this event is that in the following three days Wallace received over 40,000 letters and telegrams, the vast majority supportive and over half coming from outside the South. This foreshadowed the burgeoning support he would receive outside the South in his four successive presidential campaigns.

One of the black students who enrolled that day was James Hood. His reflections on the situation a quarter century later, in an interview with the Tuscaloosa News, are revealing. “I was more concerned about ‘me’ than I was about the impact I had on others,” Hood said in the 1989 interview, quoted at length in Stephan Lesher’s 1994 biography, George Wallace: American Populist.

Even more interesting was Hood’s assessment of Wallace as “one of the most astute Southern politicians that this country will ever know.” Hood maintained that Wallace’s position “had nothing to do with race” but about the very constitutional principles Wallace put forth. He also noted that Wallace’s stand was “courageous” and “very noble” because of the risks he took regarding his safety and the possibility of being jailed in order to keep his word to do what he promised.

Hood did not consider Wallace a racist: “I think the problem of racism is an ingrained idea that people have and are willing to deny another whatever is justly theirs simply because of color. I don’t think George Wallace did that.”

Needless to say, these words are not among those inscribed on the memorial to Hood that now sits outside that schoolhouse door today.

The following years were telling. With the unexpected success of Wallace in the Northern primaries and instances such as the Watts riots in California, the country could not deny that racial tension and social unrest was not something confined to the South. Wallace railed against “pointy-headed intellectuals” and posed a threat to lawlessness, big-business contracts, tariffs, subsidies, and wealth concentration. He played as well in Rust Belt crowds as he did in the South.

Barry Goldwater became the first presidential candidate to echo, if not incorporate wholesale, the views of candidate Wallace when Goldwater became the Republican nominee in 1964. Wallace withdrew from the race in July on the CBS program Face the Nation, declaring his mission had been accomplished. “I was the instrument through which … the high councils of both major political parties ‘conservatized,’” he said.

Wallace ran as an independent in the 1968 presidential election, winning 9.9 million votes (13.5 percent of the total) in the general election. Over four million of those were from outside the South. Richard Nixon won the presidency by sounding a lot like Wallace without a Southern accent. The “Southern Strategy” was born.

Back in Montgomery, Lurleen Wallace died in office in 1968. She was succeeded by Lt. Gov. Albert Brewer. Wallace challenged him for the office in the 1970 election, knowing that the governorship was his springboard to run again for president in 1972.

Among the many interested in this state contest was the occupant of the White House. Looking ahead to his reelection attempt, President Nixon began taking the populist threat from the Deep South very seriously, and was intent on knocking Wallace from the race. Nixon became involved in the Alabama gubernatorial contest, as revealed three years later in testimony before the Senate Watergate Committee. Nixon’s personal attorney Herbert Kalmbach disclosed how he made secret payments to the Brewer campaign totaling $400,000 from Nixon campaign funds.

Wallace won a close election in a runoff. His inaugural address contained no mention whatsoever of segregation. What he did say was that “Alabama belongs to all of us—black and white, young and old, rich and poor alike.”

Wallace had gained the attention (if not the respect) of both major parties and the media. It was clear the elites were no longer ignoring him. Neither was a demented gunman, who diverted his plans of assassinating Nixon and switched his focus to Wallace.

It is easy for us to forget just how well Wallace was doing in that 1972 presidential race, before calamity struck. He was riding high in the polls just before he was shot five times by Arthur Bremer in a parking lot in Laurel, Maryland. He would go on to win more Democratic primaries than anyone except the nominee, George McGovern, in a five-way race. Wallace’s popular vote was less than two percent behind McGovern’s.

Against the lackadaisical McGovern, Nixon went on to win reelection in one of the largest landslides in American history. We are left to only imagine the entertaining spectacle of a Nixon-Wallace debate.

Among the many misconceptions about Wallace today is the idea that he must have been delusional to have ever thought he could actually win the presidency. But Wallace himself was clear-eyed about using his candidacy to send a message. Before entering the 1972 Florida Democratic primary, he said: “I have no illusions about the ultimate outcome. But we gonna shake up the Democratic party. We gonna shake it to its eye-teeth.”

Wheelchair-bound as a result of the shooting, he continued to be a significant political figure for decades. On June 12, 1976, Jimmy Carter paid a visit to the governor’s mansion in Montgomery to publicly receive the endorsement of Wallace. Carter followed Nixon in successfully riding Wallace’s issues to the White House.

After being out of office for four years, Wallace reentered politics a final time in 1982 to run for governor. Twenty years after “Segregation Forever,” Wallace displayed his political magic once more by openly courting and largely receiving the black vote.

Ronald Reagan had a sleeker smile and a finer touch, but he, too, rode the Wallace wave and walked those same footsteps that Wallace had first dared to tread. He won in 1980 and 1984. His vice president, George H. W. Bush, ran a similar campaign in 1988 against his liberal opponent, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis. Bush’s ad critical of Dukakis’s mishandling of the furlough of violent felon Willie Horton could have been crafted by Wallace aides.

In 1992 the same Wallace Democrats who had assured Reagan’s victory 12 years earlier booted Bush from the presidency. James Carville, the campaign coordinator for Bill Clinton, called Wallace “the best campaigner” of modern times. He knew how to “put the hay down where the goats can get at it,” Carville said.

Wallace retired from government for good in January 1987, handing over the Alabama governor’s chair to the first Republican since Reconstruction. Six months later, Jesse Jackson came for that famous chat with Wallace, in a visit covered by national media. A downtrodden Wallace repeatedly referred to himself as “just a lame duck.” “You should not look at yourself as a lame duck, because it’s not true,” Jackson said. “Even now many people hear your voice.”

above: Alabama Gov. George C. Wallace, right, is shown at the Governor’s Mansion in Montgomery with a meeting between presidential hopeful Rev. Jesse Jackson in this July 21, 1987, photo. (AP Photo/Dave Martin)

In the years after leaving office, Wallace seemed consumed with his legacy. He was terrified that he would be remembered only as the figure portrayed by the media and liberal historians—the racist bigot standing in the schoolhouse door. He spent a great deal of time in those final years apologizing and attempting to explain.

What were Wallace’s true feelings and convictions? Did he change over time from reflection, or did he just change to fit the time and place and further his personal redemption and political expediency? One may never know.

Wallace died of respiratory and cardiac arrest on the night of Sept. 13, 1998, the same night actor Gary Sinise was awarded an Emmy for his unflattering role as Wallace in a television miniseries. Hollywood clearly did not buy Wallace’s expressions of regret.

We are left with two main takeaways from the life and impact of George Wallace. First, if his later years were an attempt at legacy control, it was an utter failure. Those on the right cannot seem to learn that trying to win points with the left and win battles on their home turf playing by the left’s warped rules is an exercise in futility. In spite of all that backtracking, Wallace is still reviled by them. His image will always be the one of racist defiance. because that image is what gains the left the most mileage. In spite of all his exertions, Wallace was never rehabilitated in the public mind.

Second, Wallace’s campaigns had an enormous influence because of the support of the people. Without question, he jerked both parties to the right every time he took to a microphone and started shaking his fist. Wallace knew it, too. “They’re all saying today what I was saying back then,” he said in his latter days. “Reagan ran on everything I ran on … He even used some of the same phrases I used.”

The Wallace of the 1960s and ’70s made possible the Reagan Revolution of the 1980s. And perhaps alone among all men, his influence was such that he pulled both major parties to the right for decades after repeatedly telling us how there wasn’t “a dime’s worth of difference” between the two.

People whose fathers voted for Wallace in ’68 and ’72 voted for Pat Buchanan in ’92 and ’96, and then their children voted for Donald Trump in 2016 and 2020. Wallace’s imprint is seen throughout the chain.

As we say in Alabama, that’s walking in high cotton.

Image Credit:

above: Attempting to block integration at the University of Alabama, Governor George Wallace stands defiantly at the door while being confronted by Deputy U.S. Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach on June 11, 1963. (Library of Congress/Public domain)

Leave a Reply