Mere pandemics cannot stop the Richard Wagner bibliography from expanding, indeed from metastasizing. Yet, even as the catalogue of new books on the famed, 19th-century German composer expands, “woke” culture threatens to drive him, and the Western civilization he represents, into a state of cancellation.

Vast quantities of ink have been lavished upon every bizarre Wagner-related subject. Wagner and vegetarianism; Wagner and environmentalism; Wagner and dogs (an “animal liberationist” before the phrase was invented, Wagner once lamented that “the worst animal of all is the human being”); Wagner and Christ, Buddha, Schopenhauer, Marx, Freud, Jung, and Tolkien. A book on Wagner’s supposed androgyny sits beside several on his alleged homosexuality—yes, for 150 years, gossips have insisted that he was getting it on with King Ludwig II of Bavaria. Completing the list are Wagner and Nietzsche and, of course, Wagner and Hitler. On that last topic the available commentary would fill a dozen houses. You name it, the Library of Congress stocks it.

Let’s not forget the specialist musicological studies on Wagner’s crucial importance to the history of conducting, treatises on how he radicalized or failed to radicalize operatic production, and biographical studies on his influence on every composer from Debussy to Dvořák. No doubt, somewhere in the world, the light of a Kindle is projecting an underemployed Ivy Leaguer’s solemn essay explicating Wagner’s world-historical impact on the rap music of Kanye West.

Into this musical fray enters Wagnerism: Art and Politics in the Shadow of Music (2020), written by long-time New Yorker music critic Alex Ross. His 784-page tome on Wagner joins a plethora of literature whose hypertrophy English critic John F. Runciman deplored back in 1913, only three decades after Wagner’s own passing, by saying: “His theories have been explained to death; hundreds of books have been written about them.” Non-Wagnerians and anti-Wagnerians are likely to respond to the expanding canon with a heartfelt “Enough already.”

Although Ross’s politics—inasmuch as he has revealed them through the pages of The New Yorker—greatly differ from this magazine’s, he has shown himself scrupulous in assessing art forms and specific artists personally uncongenial to him. Like Evelyn Waugh, who extolled Elizabeth Bowen’s literary journalism precisely because “unlike most of her colleagues, she likes books,” Ross shows a fair-mindedness toward all those whose works he reviews in his columns.

Ross’s enthusiasm for music per se is rare among the shrieking, statue-toppling, proudly ahistorical undergraduate maenads of 2020, who, left to themselves, can’t tell Bruckner or Bartók from Beck or Björk. This is a generation whose knowledge about Beethoven is contaminated by the idea that his Ninth Symphony is problematic because it somehow expresses the feelings of a frustrated rapist, and who believe that Bach’s Fifth Brandenburg Concerto is really about feudalism, both theories of feminist academic Susan McClary, the Chief Wiggum of 1990s pseudo-musicological law-enforcement.

On a good many earlier occasions, above all in his artistically and commercially successful book, The Rest Is Noise (2007), Ross has demonstrated a rare talent for conveying in cold print, with unsurpassed vividness, the sound of specific musical scores. He manages this feat again when discussing Wagner in a recent New Yorker column. A Martian who had never heard “Ride of the Valkyries” but who knew the basic constituents of earthlings’ orchestras and musical nomenclature could gather the excerpt’s gist from Ross’s description:

The convocation of the nine Valkyries in Act III of Walküre is Wagner’s finest action sequence – a virtuoso exercise in the massing of forces and the accumulation of energy. At the beginning, winds trill against quick upward swoops in the strings; horns, bassoons, and cellos establish a galloping rhythm, at medium volume; then comes a trickier wind-and-string texture, with staggered entries and downward swooping patterns added; and, finally, horns and bass trumpet lay out the main theme. Successive iterations of the material are bolstered with trumpets, more horns, and four stentorian trombones, but the players are initially held at a dynamic marking of forte, allowing for a further crescendo to ff. When Rossweise and Grimgerde appear, filling out the Valkyrie ensemble, the contrabass tuba enters fortissimo beneath the trombones, giving the sense of maximum reinforcements arriving.

above: Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim onstage with the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra at the forest stage (Waldbuehne) in Berlin, Germany, August 25, 2013, at a concert where the works of composers Verdi, Wagner, and Berlioz were presented (photo by Matthias Balk/Alamy Stock Photo)

Such an acute description aggravates regret that, in Wagnerism, Ross has let his gift for vivid musical description rust unexploited. The outcome inspires bewilderment over what his book’s intended market might be. Wagnerism is surely far too long to interest the complete tyro, who would be happier with some online encyclopedia entries. Yet the perfect Wagnerite—the sort of bore who can, and does, memorize what Wagner had for breakfast on Sept. 22, 1877—will know the book’s information anyhow.

While there are a few unexpected omissions, one of which is Roger Scruton’s Wagner discourses, too often Ross’s tome reads like a database. It conveys the impression that Ross simply typed the word “Wagner” into JSTOR, faithfully notating each journal reference he could find, regardless of their authors’ expertise concerning the actual operas.

Of course, mere database-trawling will delight the “woke,” by its innately hyper-egalitarian nature. For the “woke,” any verbiage—however peevish or glib—against the canon of Western civilization is legitimate, whereas considered conclusions derived from a lifetime of wrestling with Wagner’s music are automatically “elitist,” “fascist,” “essentialist,” “triggering,” or whatever other content-free adjective our adolescent enragés have adopted as bellyache-du-jour by the time this article goes to press. For example, Ross mentions not only that Marx railed to Engels against the “Bayreuth fool’s festival of the official town-musician Wagner,” but that Donald Trump, “after an encounter with the Ring at the Met in the 1980s … said to the Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown, ‘Never again’.” Such hyper-egalitarianism’s merit from the standpoint of intellectual life, as opposed to woke acclaim, is less obvious.

above: the cover of Alex Ross’ 2020 book Wagnerism: Art and Politics in the Shadow of Music (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

For the non-woke crowd, Ross’s most satisfying chapters are his first and his 11th. In the former, he supplies a brisk, exciting account of Wagner’s demise in Venice and its immediate aftermath. Ross makes this well-known tale fresh again through such details as the “five thousand telegrams [which] were reportedly dispatched from Venice in a twenty-four-hour period.” This reviewer had hitherto never realized how many poems Wagner’s death prompted. Algernon Charles Swinburne wrote one; and in Dunedin, New Zealand, novelist Fergus Hume produced “a sonnet hailing Wagner’s ‘Aeschylean music’.”

With his 11th chapter, Ross traces the history of Wagner’s appeal to left-wing thinkers. Most of this history has been long absent from generalist surveys, although Bernard Shaw’s interpretation of Der Ring des Nibelungen as an allegory of late-capitalist rule remains famous, as to a lesser extent does the overlap in Dresden between Wagner’s political activism and that of anarchist Mikhail Bakunin. Ross notes that journalist Theodor Herzl attended Wagner productions whenever he could. German socialist August Bebel and Austrian labour leader Victor Adler regarded Wagner as a valued, if wayward, ally. Much earlier—in fact before the Ring’s actual music had become available—socialist Ferdinand Lassalle grew delirious from simply reading the tetralogy’s librettos:

I am still in endless excitement like a foaming sea, and days and weeks will pass before I can concentrate the soul sufficiently undivided upon the arid statistical and economic investigations to which my next period is devoted.

Bertolt Brecht, of all people, would likely agree with Lassalle, for he admitted to a teenage crush on Wagner’s music, calling it “herrlich” (splendid).

In France, socialist Jean Jaurès revered Wagner’s Der Meistersinger von Nürnberg (“The Master-Singers of Nuremberg”), though the mystery-play ritualism of Wagner’s opera Parsifal affronted his sunny French intellect. Romain Rolland, when still one of France’s most renowned novelists—rather than an embarrassing apologist for Stalin—viewed Wagner’s concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, (“artistic synthesis”), the unification of many art forms, as a purgative social force.

Although abhorred by prominent Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy, Wagner’s operas were popular in that country as well, making frequent appearances in Russian theaters well before 1917. Their admirers included Nicholas Roerich, the Symbolist-Theosophist painter who became former American Vice President Henry Wallace’s preferred guru; Wallace saw nothing amiss in addressing Roerich as “Parsifal.” While the early Bolshevik leadership tolerated Wagner’s operas, they disappeared from Soviet stages after 1933, save during the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, when the regime allowed Eisenstein to direct Walküre. According to Ross, Parsifal remained unstaged in the country till 1997.

above: photograph of Richard Wagner taken in 1861 while he was in Paris for the premiere of Tannhauser (photo by Pierre Petit, public domain)

No less a revolutionist than W.E.B. Du Bois, when not penning such Goebbels-like invectives as “it takes extraordinary training and opportunity to make the average white man anything but a hog,” became positively lyrical in his rapture over Lohengrin:

It is a hymn of Faith. Something in this world man must trust. Not everything—but Something. One cannot live and doubt everybody and everything.

Oh, can’t one? A pity that Du Bois never lived to behold Rupert Murdoch’s 21st-century Australian gutter-press and its televisual annexes. There he would find nihilism flourishing not as a mere byproduct, but as the divinity in which millions live and move and have their being.

In short, sincere Marxists—and sincere democratic socialists of the Adler-Jaurès studio—had the inestimable advantage of not being cultural Marxists. They nowhere imagined that they served the oppressed masses by shouting down as a product of “white privilege” any artistic creation that makes more cognitive demands on its audience than do Cardi B’s homages to her own pudendum.

Had the rest of Wagnerism fulfilled the promise of its finest portions—which include a thorough, dignified debunking of the tenacious myth that Auschwitz’s death-factory resounded to Wagner’s music—a recommendation would be easy. Alas, Ross has devoted excessive space to feminist and gay identity politics, not because these matters possess any save the most tangential relevance to Wagner’s output, but because…well, because.

Ross differs from the Woking Class in that he is cultured and educated, whereas the Woking Class is neither; on the contrary, it rejoices in its sheer ululating ignorance, as did Maoist China’s Red Guards. But, with the seventh chapter above all, Ross turns his literate, elegant English to the same malign purpose at which the Woking Class’s gonadal patois aims: appealing to sophomoric sanctimony. In such passages, his prose could almost have been written by a congenitally deaf author. It is hard to postulate a more damaging fault in any musicological exegesis, but it is equally hard to postulate any fault more readily misconstrued by the politically correct brigade as a virtue.

above: Emil Fischer in the role of Wotan in Wagner’s opera Das Rheingold at the 1889 New York Premiere (Photo by Falk, Met Opera archives)

The hedging evident in Ross’s section on Wagner and Israel is both curious and inopportune. It is well known that Israel bans the performance of Wagner’s music on government property. This prohibition deserves no more polite a name than “cancel culture.” As Ross himself notes, conductors Daniel Barenboim, Zubin Mehta, and Asher Fisch have experienced for themselves the social costs of trying to breach it.

True, the ban has varied in the strictness with which it has been imposed. Even at its most draconian it failed to prevent Israelis from listening to Wagner on records, a prohibition technologically infeasible today, given the global reach of music-streaming services. But although Ross himself shies away from advocating the ban—a welcome change of heart, since years ago he considered it to be, on balance, defensible—he leaves unchallenged both the ban’s hypocrisy and its destructiveness.

To take the hypocrisy first: secular liberals who defend Netanyahu-style censorship of Wagner and Richard Strauss can be relied on to scream like proverbial banshees when anyone suggests censorship of other artistic products such as Lady Chatterley, Lolita, Portnoy’s Complaint, The Satanic Verses, Charlie Hebdo, or Larry Flynt’s collected theologizing.

Yet the destructiveness of Israel’s Wagner ban, less immediately apparent than its hypocrisy, is still profound. For as long as the ban lasts, it condemns Israel’s classical music culture to provincialism. Those who want to become instrumentalists good enough for any professional symphony orchestra outside of Israel must develop technique, which encompasses what Wagner’s and Strauss’s compositions demand, otherwise every job audition will end in humiliation. Besides, an opera company that rejects Wagner and Strauss scarcely deserves to be called an opera company at all.

Ross, who understands these truths as deeply as any other intelligent commentator of our time, refrains from spelling them out. His attitude amounts to an opportunity missed, making Wagnerism stand in sharp contrast to the exceptional abilities he exhibited in his earlier work, The Rest Is Noise.

Yet Ross was born only in 1968 (making him almost a child prodigy by New Yorker contributors’ standards), and none of us should presume to set predictive limits on how he can adorn future American literature. Especially when, near the end of Wagnerism, he can write the following:

As an American ashamed of my country’s recent conduct on the international stage, I reflected on the fact that much devastation has been visited on the world since May 1945, and that very little of it has emanated from Germany. The endlessly relitigated case of Wagner makes me wonder about the less fashionable question of how popular culture has participated in the politics and economics of American hegemony.

That is Ross at his best. Dare we call him le paléocon malgré lui? (“Paleocon in spite of himself?”) It strengthens the hope, first, that he will eschew reinterpreting his role as that of an appeaser to the Woking Class; and, second, that he will recollect the terrible warning—attributed to both Fulton Sheen and William Ralph Inge—for those who rashly embrace the Zeitgeist:

If you marry the spirit of your own age, you will be a widow in the next. If you marry the spirit of the next age, they will build you a handsome sepulchre, but perhaps you will be killed before your day comes.

Image Credit:

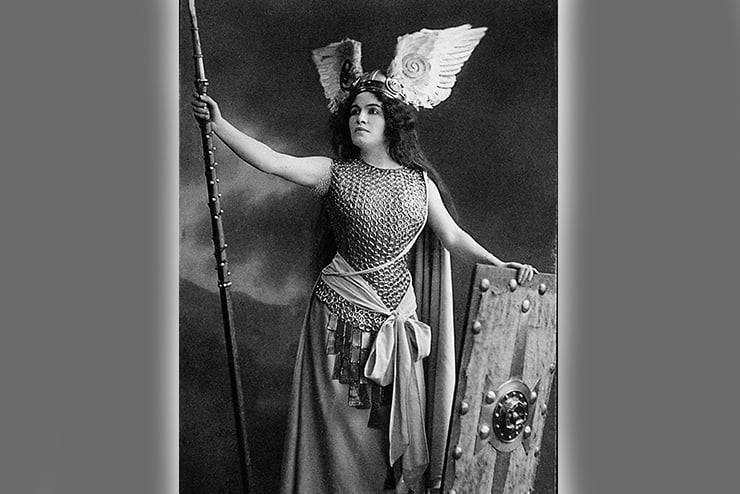

above: Madame Charles Cahier as Brünhilde in Die Walküre (The Valkyrie) photograph by Victor Angerer (Theatre Museum, Vienna/Alamy Stock Photo)

Leave a Reply