[What follows is a meditation on T.S. Eliot’s poem “Little Gidding.” All indented quotations, with apologies to their author, are taken from Eliot.]

What we call the beginning is often the end

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

The end is where we start from . . .

The first step, they say, is to admit you have a problem. That’s true of saints on the Romans Road and of drunks on the Road to Sobriety.

It’s also true of conservatives and the Ship of Civilization.

The problem that needs admitting is sin and its conjoined twin, death. And what’s happened is that conservatives no longer recognize this, and so stumble around, intoxicated by a specious sentiment for something called the Restoration of the West. This thing we call the West—a vessel more intricately constructed than we are willing to admit and more complex than our Manichaean imaginations will permit us to remember—has smashed against the rocks of modernity. We are grasping at the flotsam of Christendom while thrashing about in the waves and hoping to rebuild the ship in the sea.

In other words, we have set our hearts on something that not only is unattainable but may hasten our demise.

Years ago, I remember, a middle-aged gold trader began attending events sponsored by Chronicles and The Rockford Institute. After one particularly fiery lecture, the man, Blake Harrison Joyner, said something that was telling. “OK, I get it,” he insisted. “I see what you’re against. And I agree. But what are you for?” Blake was as honest as he was urgent. And his question stuck with some of us, to the extent that, whenever we hear it repeated—and the frequency is regular—we call it the Blake Joyner Question. What are you for?

“True conservatives are for everything that is good” is not a satisfying answer. But it’s a true answer, as is “the Faith once delivered,” and even “God, Family, and Country.” The trouble comes in attempting to describe an ism, like conservatism, without degrading it into an ideology. “What we are for” cannot be distilled into sound bites or mere principles, because apart from their proper context, words like tradition and family—not to mention the “values” or “cultural heritage of Western Christian Civilization”—fall straight down the well of politics and public policy.

The business of writing clearly and concisely about “what we’re against” has, above all else, the particular value of tearing down misplaced hopes. Princes, to paraphrase the Psalmist, cannot be trusted to defend what is true and good and lovely. And our princes today are awarded their purple through what we call the “democratic process”—a ridiculous process made all the more silly by television and the internet.

Chesterton described the democratic process as a bunch of drunks yelling at one another in a tavern he called the “Blue Pig.” The saving grace of the Blue Pig was that, in the end, after chairs were thrown and bottles broken, the men sobered up and went on with their lives, knowing full well they had been at a tavern. That grace was lost when Americans elevated the democratic process to the realm of the sacred, transforming our contests big and small into battles of light versus darkness, good versus evil. This sacralization of the pub of democracy was achieved by the eminently conservative William Jennings Bryan and the suffragettes, who insisted that the realm of light would be more likely to triumph if only it were better represented. Now we sit in our coeducational tavern, FOX News on every flatscreen, stone-faced and deeply concerned that evil is triumphing while good people are doing nothing.

To laugh at the process would be to blaspheme.

Nonetheless, our refusal to laugh, to see the Blue Pig for what it is, gives us such odd outcomes as pro-life quiverfull evangelicals endorsing an abortion-flip-flopping Catholic, who then turns around and endorses an abortion-flip-flopping liberal Mormon. Said Rick Santorum, when throwing his weight behind the man who paved the road to Obama Care, “Above all else, we both agree that President Obama must be defeated. . . . The task will not be easy. It will require all hands on deck if our nominee is to be victorious. Governor Romney . . . has my endorsement and support to win this the most critical election of our lifetime.”

. . . Last season’s fruit is eaten

And the fullfed beast shall kick the empty pail.

For last year’s words belong to last year’s language

And next year’s words await another voice.

The next election will be the “most critical election of our lifetime.” That is the misplaced hope that true conservatism seeks to destroy. But that false hope is quickly born again if context is not established. After all, will God bless a nation that countenances gay marriage and abortion? Can our children survive the onslaught of the Department of Education and liberal, federally funded universities? Won’t ObamaCare destroy our businesses and nonprofits by forcing them to fund contraception? Will our military survive another adventure in nation-building? Conservatives must do something to save America.

Sin is Behovely, but

All shall be well, and

All manner of thing shall be well.

When Eliot wrote those lines, attributed first to Julian of Norwich, he spoke not only of the felix culpa that moved God to the supreme glory of Incarnation and Cross, but of an awareness of sin as the condition necessary for right thinking. And “all shall be well,” because Incarnation and Cross are both fact and focal point of historical reality. Nothing can truly be seen apart from the reality toward which sin has heaved us.

Thus, the question of “what we are for” cannot be answered with prooftexts that offer mere principles, the foundation of an ideology. We must see the texts in the context of the narrative.

History may be servitude,

History may be freedom. See, now they vanish,

The faces and places, with the self which, as it could, loved them,

To become renewed, transfigured, in another pattern.

Apart from a deep recognition of sin in the narrative, we fall—cannot help but fall—into the Puritans’ trap of building our shining city on a hill, the harbinger of the Kingdom of God. But New England Puritanism was dead after three generations, and each of the three generations fought bitterly with their children to stay within the bounds of the covenant, or “halfway covenant.” Yet it doesn’t matter that most modern conservatives don’t explicitly espouse postmillennialism. Without much effort, we instinctively seek to build our New Jerusalems. We think a policy or a president can ring the bell of the Sexual Revolution backward. We fight gay marriage with statistics about children and depression. We tell each other that it is a sin not to vote, and make pronouncements about the importance of elections within the scope of our brief lifetimes. See how they vanish . . .

Whatever we inherit from the fortunate

We have taken from the defeated

What they had to leave us—a symbol:

A symbol perfected in death.

Death is the twin reality that sin causes. It has defeated all our heroes, all of our ancestors, all of the fortunate ones. We die. But also, America dies, the South dies, the Republican Party dies. (They do not belong to an unmovable Dar al-Yahweh.) Even our churches die. (“I will remove thy candlestick.”) This was the point of Saint Augustine’s City of God, written to calm the fears of Roman Christians who thought that the barbarian overrun of their Eternal City might mean that their faith was in vain.

American conservatives float between the postmillennialism of the Puritans and the premillennialism of modern evangelicalism. We look for a pattern in the news that bespeaks the rise of Antichrist. And if we don’t intervene in this pattern, and put ourselves back on track toward the Kingdom of God, our only hope is a secret rapture, a supernatural escape. Our imaginations are frozen in this eschatological winter. Indeed, we cannot escape the idea that our actions must somehow shape the course of history. History may be servitude. We say, “What are conservatives for?” And we mean, “What must we do to halt the progress of evil?”

There is nothing conservatives can do to halt the progress of evil. This is not a satisfying answer to those unwilling to embrace Incarnation and Cross and to see the way these illuminate our time with pentecostal fire. Yet this is the only answer if sin is our context and death our inevitable end. Within the biblical and Augustinian narrative, every horror of the evening news, every outrage of the day from a Rose Garden press conference, every tragedy perpetrated by a crazed gunman should be met with the sober reply, of course.

You are not here to verify,

Instruct yourself, or inform curiosity

Or carry report. You are here to kneel

Where prayer has been valid.

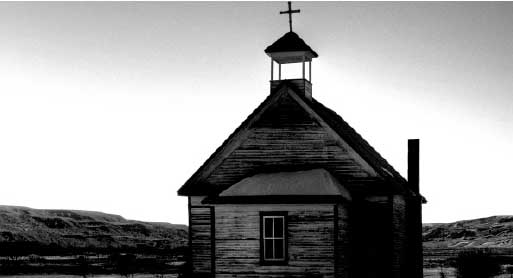

Of course, this sober reply is not an appeal to quietism. Prayers offered at Little Gidding or elsewhere are not for nothing; they are in fact everything. Prayers offer the potential benefit of divine restraint on the evil that surrounds us, on the darkness that envelops as the midwinter sun sets. But also, prayer begins with a surrender to the inescapable reality of sin and death. You are here to kneel. To kneel here in the present is to see history for what it is.

. . . A people without history

Is not redeemed from time, for history is a pattern

Of timeless moments. So, while the light fails

On a winter’s afternoon, in a secluded chapel

History is now and England.

From the vantage point of our knees bent in prayer, history is freedom. Not because we are free of all obligation, but because we are free of the burden of saving our people, our party, our country, and even ourselves. Through Incarnation and Cross, Divine Love has already saved us, destroying sin and death, bookending history, and leaving us with timeless moments in which to seek the good and its Author. Death is compelled to give way to life, a pattern we already witness. And so the death of what we call the West is not the end but the beginning.

Now is the “conservative moment”—not because of any election or any ideology or political plan, but because we are present and alive. The end is where we start from.

And so the answer to “what we are for” is the Faith, life, family, country, church—in short, everything that is good. We are free to write a poem that may never be published; start building a cathedral whose completion we will never see; bring children into an uncertain, fallen world; laugh at politics and vote anyway. We are free to be truly for these things, to be conservative in the only meaningful way possible, if and because we have assumed the posture of prayer.

With the drawing of this Love and the voice of this Calling

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Leave a Reply