What happened to Minnesota—the stolid Nordic-and-German prairie republic, the mother of vice presidents, the place where Democrats were “Farmer-Labor” and seemed to mean it? Lately, when it comes to statewide office, Sven and Ole have been serving up not their usual hotdish and egg coffee but an uncharacteristic booya of Slavs and Jews, Easterners and wrestlers.

That the menu had changed was obvious by 1990, in what we might call the Minnesota’s Rudy Awakening. Iron Range dentist and Democratic-Farmer-Laborer Gov. Rudy Perpich was a relic of a day when a double prole—pro-life proletarian—could still rise to the top of his party. He may be best remembered for an unsuccessful states’ rights lawsuit against the Reagan administration concerning the use of the National Guard abroad. Another Rudy, Senator Boschwitz, who fled Nazi Berlin as a child, rose from a New York upbringing (the beginning of a Gopher State trend) to become the plywood king of the rapidly suburbanizing Upper Midwest. That success and the direct-mail skills he acquired along the way carried him to Hubert Humphrey’s old seat as a Republican—or an “Independent-Republican,” as they were called in 1978. He was, and is, a top fundraiser, who would soften his tough-guy pitches with a girlish smiley-face signature.

In 1990, Boschwitz was seeking his third term in the Senate; Perpich, his fourth as governor. Opposing them were Paul Wellstone, a Carleton College professor of political science (and 1964 Atlantic Coast Conference wrestling champion) who collected volunteers like Boschwitz did cash, and Arne Carlson (imagine Nelson Rockefeller, but poor, Swedish, and actually born in New York), who wanted Perpich’s job. The Independent-Republican nomination went to Jon Grunseth, however, an Adonis with social views more palatable to regular churchgoers. Not so palatable, though, was the late-October story that he had hosted nude pool parties a decade earlier and had chased and pinched one of his teenaged daughter’s bikinied friends. True or not, the charges were fumbled by the candidate, who desperately blamed Perpich for cooking the whole thing up, before finally ceding his ballot spot to Carlson. (The last-minute charge that emanated from a Boston women’s group smells more like an effort to put the Roe-friendly Carlson back into the race).

While this fiasco unfolded, Wellstone rode around in his $3,500 green school bus and ran a remarkably cheap and innovative television campaign. “Fast Paced Paul” squeezed in all of his major positions before he rushed onto the bus, implicitly mocking the high budget of the other campaign. Ultimately, though, Senator Boschwitz was done in by his own people. Tired of putting up with constant references to Goliath, the Boschwitz campaign sent out a letter insisting that their candidate was the “Rabbi of the Senate” and a much more authentic Jew than Wellstone. There are better ways to win an election in Minnesota than accusing your opponent’s wife of practicing Christianity. The letter was the talk of the state over the last weekend of the campaign, and Wellstone’s final ad morphed that signature smiley face into Mr. Yuck, the children’s poison warning.

In 1994, John Marty, son of Lutheran theologian Martin Marty, took on Carlson, only to show that voters, even liberal ones, prefer a secular Republican to a religious Democrat, and that turning down PAC money is not a smart move. Boschwitz decided in 1996 that, if Wellstone had the best political adman in the country, he would counter with the worst. Arthur J. Finkelstein, king of blunt-force attack ads, chose to run spots labeling Wellstone “embarrassingly liberal.” (Everyone knew Wellstone was liberal, and, with Rod Grams now the state’s junior senator, voters might have cut even the old Iron Range Communist Gus Hall a little slack.) Wellstone ran a more conventional campaign this time, with Beltway advisors and money, but he needn’t have bothered. Boschwitz managed to top his 1990 seppuku by accusing the incumbent of having participated in a 1960’s flag-burning at Chapel Hill. Some elementary rules were ignored here: Produce solid evidence; let the press handle it; and, most importantly, never look desperate. Boschwitz has since concentrated on fundraising for others; Finkelstein reportedly lives in Massachusetts with his common-law (or civil-law or constitutional-law) husband and advises campaigns in such places as Rumania.

Wellstone is not the only populist on the prairie. David Lebedoff is a Minneapolis lawyer who has been profiling a certain class of people since the 1970’s—in The New Elite (1981) and its told-you-so follow-up, The Uncivil War (2004).

There is no shortage of paradoxes in Lebedoff’s observations. What he calls the New Elite grew out of aptitude testing, but there is no admission requirement other than simply feeling one is smarter and, thus, more entitled. A person’s background is admirably irrelevant; it is only important that he turn his back on it. “Reforms” aiming at proportionality, diversity, and openness prove, in practice, to be less democratic even than the old smoke-filled rooms. Politicians once knew the people and hired wonks to craft policy; now the pols are the wonks and need James Carville to explain the people to them. Most tellingly, because they are smarter and righter, New Elitists have no need to consult the other side and, thus, often cannot be bothered to think for themselves. Universities that once made dumb kids smart now make smart kids dumb, and we end up with an emotional and uncivil Ditzpolitik, directed by large but atrophied brains.

Lebedoff’s heroes are the restrained majoritarian jurists Felix Frankfurter and Oliver Wendell Holmes, who told us, “A page of history is worth a volume of logic.” That might be the motto of the “Left Behinds,” Lebedoff’s term for everyone else. The rejection of such common sense by the best and brightest has plagued the Democratic Party, in particular, over the last 40 years, leaving them vulnerable to the likes of Reagan and the Bushes, who can speak to the people as a corporate whole—and to the rare elitist such as Bill Clinton, who can perform in drag. That Wellstone could use armies of the elite as foot soldiers, while remaining outside of it himself, was quite a feat.

The Wellstone “cult” itself is noteworthy. Political crushes such as the McCarthy, McGovern, Anderson, Hart, and Dean campaigns last about 12 months and cover 50 states. Wellstone’s went on for twelve years in one. “Don’t park the bus” stickers are still common, as are those that ask, “What would Wellstone do?”

The senator was often forced to defend his votes on such things as military expenditures and the Defense of Marriage Act—to his New Elitists. The only thing he had to explain to Minnesotans at large was the breaking of his two-term pledge, a decision that cost him his life when his campaign plane crashed 11 days before the 2002 election. The Uncivil War uses the degeneration of his memorial service into a political rally as a prime example of the New Elite out of control.

Bill Hillsman is another angry Minneapolitan, but instead of issuing dark, Cassandrine warnings from the sideline, he chooses to get into the fight. Dragooned into the 1990 race as Wellstone’s only acquaintance in advertising, he found that commercial practices not only adapt well to political campaigns but improve the standard. Candidates are not sold like soap, but maybe they should be. (David Ogilvy’s adage comes to mind: “The customer is not a moron. She is your wife.”)

Hillsman prefers candidates who are straightforward, likeable, and unorthodox, and, teamed with the right man, the results can be quite devastating to what he terms “Election Industry, Inc.” Besides the ads that first elected Wellstone, he worked on Jesse Ventura’s upset in 1998, Ralph Nader’s Florida campaign in 2000, and Ned Lamont’s primary displacement of Joseph Lieberman in 2006. Most of these battles, and Hillsman’s ideas, are written up in his 2004 book, Run the Other Way.

Jesse Ventura left his native Minneapolis for the Navy SEALs and a career in professional wrestling. In 1990, he won the mayor’s job in Brooklyn Park—a farming burg like its Michigan namesake, until postwar sprawl (and, no doubt, much Bosch-witz plywood) transformed it into a cross-section of modern American life. It was the perfect background when the Reform Party came knocking in 1998.

Norm Coleman came to St. Paul from the original Brooklyn and, after many years of prosecuting for the state, ran for mayor in 1993. His reelection after switching parties so impressed the GOP that they chose him to face his former boss, Attorney General Hubert H. “Skip” Humphrey III. All assumed that Coleman and Ventura would split the fiscal conservative vote and Humphrey would sail to victory. Humphrey made sure Ventura was present at all debates—a blunder of Boschwitzian proportions.

Ventura flanked Coleman on the right by attacking his use of city funds to spur development. That, he said, was the province of the private sector. When the subject changed to the Defense of Marriage Act, he told a teary story of a friend’s resentful parents barring his lover from attending his deathbed. Ventura understood centrism need not mean tepid difference-splitting. A wide range of positions with the right fulcrum will do the job as well, and is more exciting: light rail and concealed carry; strict construction and sodomogamy. (This strategy is counterintuitive but hardly new. You can see it develop from Napoleon and Bismarck through Mussolini, and it is visible in the ping-pong name of the original “third way” centrists, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party.)

Ventura’s deathbed story inspired Hillsman to come aboard, and viewers were treated to another entertaining Halloween. The ads featured boys spouting Ventura’s talking points over his plastic action figure, and Jesse “The Body” was depicted as Rodin’s Thinker (Jesse “The Mind”). They got people talking, cost little to make, and local television stations would run them for free on the news.

Just as Honda once sold biking to nonbikers, Ventura sold nonvoters on voting. Every sixth voter registered on Election Day, and a majority of them chose Jesse (as did a plurality of the rest of Minnesota’s voters). Coleman held his new base, finished a respectable second, and was well placed for a future run. As for the favorite, voters took the ballot literally: Whether it said “Skip Humphrey” or “Hubert the Third,” they did, and he was. (Humphrey now heads, appropriately, the state’s AARP chapter.)

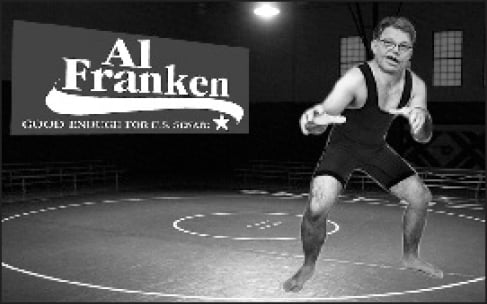

This past February, comic and radio star Al Franken announced his intention to run for Coleman’s seat, and his name is already eclipsing “Ethiopia Out of Somalia” as the Twin Cities’ hot new bumper sticker. Franken grew up in St. Louis Park, a Jewish suburb of Minneapolis. He wrestled (of course) for his prep school before attending Harvard and making a career at Saturday Night Live—effectively trading states with Norm Coleman.

Lately, his books have been selling like mini donuts, but his wobbly radio venture, Air America, lacked a fundamental business need—need, itself. Launching a liberal network today is like stocking the pond with water.

How will Minnesotans regard Franken, come Election Day? Is Franken another Wellstone? Only if, by “Wellstone,” you mean a “progressive Jewish wrestler.” But, whereas Wellstone offered organization without money, Franken has money without organization. Is Franken another Ventura? Only if, by “Ventura,” you mean “an opinionated comic actor.” Unlike Ventura, Franken has never won an election before running for Senate. Is he a New Elitist? His book titles fairly drip with condescension—as do the people who buy them. It will be hard to shake this one.

Can Bill Hillsman help him? Hillsman has done work for both Air America and Franken’s chief DFL rival, trial lawyer Mike Ciresi. But remember the warning of another adman, Bill Bernbach, that nothing will kill a bad product faster than good advertising. Another Hillsman client, Kinky Friedman, failed in the end, despite having more experience than Franken: He once ran for justice of the peace.

Elites, Election Industry, and experience aside, Franken’s biggest albatross may simply be fellow Democrat Sen. Amy Klobuchar. Five of the last six Senate races were lost by the party holding the other seat. The opposition will be energized, and Minnesotans have sampled divided government and like the taste.

In the meantime, look for a civil war in the DFL as the normal white folks—er, experienced public servants—try to keep the stargazers from hijacking their party. If that means that the era of Gopher Goofiness is drawing to a close, well, it was fun while it lasted.

Leave a Reply