We Episcopalians—we’re just so special, don’t you know? We worship in such special ways. Our churches look so special, as do we ourselves—an indication of our social gifts. And when we fight, when we commence to break the church furniture over one another’s heads—at such moments we’re just, you might say, disgustingly, regurgitatingly special; so special that many of us hope no one is watching. We know better than that, nonetheless. A specially contrived disaster, in particular one with spiritual implications, is for many irresistible. Our ongoing disaster is one of those.

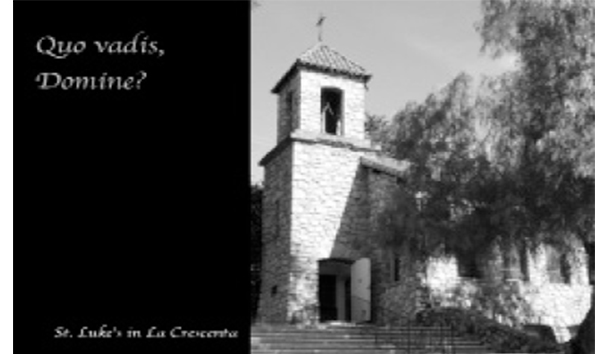

Here, as I write, is a compelling headline from the New York Times: “Breakaway Church Gives Up Property.” A California parish of the Episcopal Church—in its own mind, a former parish, having disaffiliated from the official church three years earlier—is surrendering title to its 85-year-old church building and, along with that, all claim to endowment monies, prized gifts of silver and silk, all that gave St. Luke’s in La Crescenta that certain Anglican cachet. Memories, too, and historical associations: Those go by the boards. It’s off to a new place—a rented chapel in a Seventh Day Adventist church in Glendale—and a new start, one untainted by associations with that once very special institution, the Episcopal Church.

Sagas like that of St. Luke’s occur with startling regularity now that thousands of the Episcopal Church’s proudest, devoutest sons and daughters have decided to chuck it to the Church; to walk as far away from it as possible in order to . . . the right word, I think, is restore. “Restoration” catches the spirit of the enterprise. A proud, prized structure is off plumb, with windowpanes broken and ceilings in ruins; in come the plasterers, carpenters, and plumbers to put things right again. That is how it is with the various renovation crews toiling to put right the Anglican franchise in North America.

Both within and without the Episcopal Church, pushback time has come in earnest. Waggled fingers and gentle reproaches no longer suffice. Episcopalians want something done about a wayward establishment—however pleasing its manners and decorative appointments—that has come closely to resemble The Huffington Post at prayer, assuming anyone at The Huffington Post would dream of praying.

Last June, in Bedford, Texas, a suburb wedged between Dallas and Fort Worth, an assembly from around the country made up mostly of ex-Episcopalians aggrieved by the Episcopal Church’s affection for loose, liberal theology formed a religious association of its own—an Anglican association. (Anglican, I should note, is the adjective that applies to all member churches of the worldwide Anglican Communion, headed by the Archbishop of Canterbury, with the Church of England at its spiritual center.) The new association to which I refer is called the Anglican Church in North America (ACNA); it is a coalition of varied groups that in recent years have sought to reverse the Episcopal lurch toward a kind of well-mannered secularism. The ACNA has its own constitution, its own governing body, its own back-door entrance to the Anglican Communion through an arrangement called “full communion” with two officially recognized Anglican provinces, Nigeria and Uganda. It proclaims Anglican theology, uses the Book of Common Prayer, and clothes its priests in Anglican vestments.

Wouldn’t you say this outfit is Anglican? Most onlookers would. Not so the Episcopal establishment, which drove St. Luke’s from its Southern California premises, having bested the parish earlier in a civil lawsuit. If no one particularly loves the modern Episcopal Church, the legal fraternity must. The EC dumps barrels of money on the lawyers it hires to contest the right of any secessionist parish or diocese to keep its property. The Episcopal Church wants that property. To do what with? To keep “Episcopal” as opposed to Anglican worship going there.

Another thing the Episcopal Church and its presiding bishop, Mrs. Katharine Jefferts Schori, like to do is depose departing clergy—in other words, declare them nonclergy, which they clearly aren’t, but the establishment must get its kicks somehow. Watching its membership and finances decline as a result of nonevangelism and the embrace of innovations—conspicuously, the gay-rights cause—provides no kicks. Prosecuting, if not persecuting, traditionalists gives Episcopal liberals (an increasingly tautological term) a sense of power and righteousness. (Never mind Saint Paul, whom the choleric liberal Bishop John Spong identifies as a “self-loathing homosexual,” concerning the duty of Christians to avoid civil lawsuits. When you want other folks’ property, you gotta fight ’em, kick ’em in the teeth, hurt ’em bad!)

A sizable number of theological conservatives remain inside the Episcopal Church, preferring the inside to the outside strategy: Don’t give the wretches (beloved as they certainly must be in theological terms) the satisfaction of running the joint to their own satisfaction. (I should note, in fulfillment of my full-disclosure obligation, that I remain a member of a large, orthodox parish in a large, generally orthodox diocese, that of Dallas.) There is among us a rebellious reluctance to surrender territory long held, sometimes at great cost.

But I wouldn’t pay disrespect to the secessionists by way of affirming a contradictory strategy. Secession isn’t always a winning idea—cf. the 1861-65 unpleasantness. In less bellicose contexts, it can set up a useful trial of rivals. I think that may be the effect of the Anglican secession.

If you look closely at the 21st-century Episcopal Church, you strain the eyeballs for indications of dynamism and vigor. Whereas in the mid-1960’s there were 3.6 million Episcopalians, it strains credulity to accept the church’s estimate of even 2.1 million today. Experienced observers think the number is far, far lower than that—maybe less than a million if you count those who actually show up at church. The financial/economic crisis has rendered various parishes and dioceses barely viable.

Why wouldn’t people come? Isn’t this a church of vast prestige, with a history of rich commitment to social service, as well as to the religious basics? Don’t people still show up to slake their religious faith in the drama and ceremony of Episcopal worship? Yes, to all this.

A couple of problems intervene. First, the present age isn’t as unquestioningly religious as, say, the 1950’s were, and even the early 1960’s. A secularist mood overhangs life, soaking up and rechanneling faith in things unseen but believed in. Barack Obama—nominal Christian, at least by comparison with his recent predecessors—is the fitting leader for such an age. I happened the other night upon a TV screening of the 1953 blockbuster The Robe and wondered who would submit such a movie today for public consumption. Mel Gibson? Notice how no other movie-maker has sought to build on the explicit Christianity of The Passion of the Christ.

Then there’s a second problem. The Episcopal Church at large—as contrasted with the church writ small, in parish and human terms—appears to have lost interest in the knotty old questions of sin and salvation, save perhaps as they relate to voting Republican or denying the necessity of taxpayer-financed healthcare. There wasn’t a specific moment when the church’s leadership turned a scornful glance on proponents of the old creeds, the old teachings, the old understandings of God as exacting overseer of our passions Who sent His Son as deliverer from those passions. The Church didn’t precisely deny the relevance of Jesus to a high-tech age. Rather, it put new spins on old words. Sin was social. We were to repent of perpetrating social injustice. Social justice, it turned out, consisted in affirming and promoting the rights of discrete groups of Americans—to begin with, women, then homosexuals. Interest grows in “transgendered” people and their quest for affirmation. Just when you think the Episcopal Church has run out of social/political causes to endorse . . . you’re wrong. It comes up with more—to the exasperation of Episcopalians who believe in fairness and justice but would like due attention paid by the church to the parlous state of all mankind, and to the consequent need for confession and repentance.

The Episcopal Church was always a socially active church, crusading for fairness in the workplace, and eventually for the embrace of all Americans—yes, that meant blacks, too—as children of God. The emergence of women as the next class to be liberated tickled Episcopal sensibilities. The church voted in 1976, contradicting historic understandings, to ordain women as priests. When homosexuals became the next to clamor for acceptance, in stepped the Episcopal Church once more, demonstrating its zeal for the cause by consecrating an openly “gay” priest—one who had abandoned his lawful wedded wife and his daughters—as bishop of New Hampshire. At the Anaheim General Convention last summer, deputies and bishops moved decisively toward the blessing of same-sex unions.

In family situations, as we know, fundamental disagreements on values generally precipitate divorce. How much deeper do disagreements get than those over the life questions, from abortion to same-sex “marriage”? The homosexual bishop’s handiwork was showing conservatives where they stood in Today’s Episcopal Church—namely, outside. All right, many said. If that’s how things are, let’s make it official. So out they streamed—four dioceses, along with hundreds of parishes, under circumstances still to be sorted out legally. The conservatives, like those at St. Luke’s, La Crescenta, maintain the right to property into which they have poured sweat and treasure. In a small number of cases, like that of Dallas, bishops permitted buyouts of the property. Presiding Bishop Jefferts Schori’s allies aren’t having any of that peaceful secession stuff. Off to court! There’s nothing, after all, like a good judicial ruling to settle a rebel’s hash.

The lawsuits of course miss the point of the whole thing, which is, will God bless the labors of those who proclaim the traditional Faith or those who seek to remodel it for a new age? It is what you might call a leading question. Why, we’re for the Faith, just as much as anyone else, the tribe of Jefferts Schori replies. All we want to do is unfold its newly discovered riches—inclusion, social justice, etc.—and what’s wrong with that? One thing wrong, possibly, is that the 21st-century Episcopal Church’s concerns mirror those of the secular society, into whose embrace the church shows signs of fainting expectantly. Why? Because, possibly, that way lies social approval and fulfillment.

There’s an obvious objection here. If the Episcopal Church is so in tune with modern society, why is it shrinking instead of growing? Because it’s out of tune with society’s deeper needs? The contest between the Episcopal establishment and its rebels—the ACNA, the conservative dioceses—could prove instrumental in defining what truly compels: the massaging of egos and grievances or the presentation of truths that align with the one great Truth that the Lord is God, that the Jesus Who rose from the dead is His Son, and that the Holy Ghost is Comforter rather than herald of new, previously unsuspected revelations. It is ground on which the conservatives might actually do pretty well.

Has the church been so wrong so long? The presiding bishop and her acolytes assert the correctness of their position, but proof awaits. Last summer at the General Convention Mrs. Jefferts Schori asserted that belief in individual salvation is heresy, salvation being social as it were. Critics of such a seemingly novel viewpoint spoke out sharply. Mrs. Jefferts Schori acted as though she had noted no more than the color of the sky at midday or the sweetness of angel food cake. Of course nobody “alone can be in right relationship with God.” What was the fuss about?

The Episcopal Church and its critics, from the inside or the outside, face a common hazard in their respective presentations of truth. It is the modern hazard of looking just too buttoned up, no matter what viewpoints one might uphold and assert. Modernity may or may not affirm the Episcopal preference for liturgy and ritual over whooping and clapping (though both expressions of the spirit take place more often than before in Episcopal churches). Seeming to offer “downtrodden minorities” a way other than political-style affirmation could also be a loser, just like too much emphasis on a Book in which the characters dress funny and say weird things.

Perhaps one shouldn’t lay short odds on that possibility. The stout contention of traditionalists is that sinners—and that’s everyone—yearn, knowingly or not, for the assurance of God’s love, meaning more than a pat on the head, a squeeze of the arm. I for one don’t worry greatly that internal squabbles over matters such as women’s ordination (some in the ACNA favor and practice it, others oppose and ban it) will deflect the witness of those who want truly to witness, not prosecute a lawsuit or stamp on critics with a fury best reserved for crickets.

The boat of the Christian Church, and not just in its Episcopal manifestation, is launched on rough seas. I have an intuition nonetheless. It is that the present age (yes, this one) may afford Christians a sublime moment for evangelism—yes, evangelism, the winning of souls, the conversion of the unconverted. The present age—I mean, all you have to do is look at our poor presiding bishop, who bleeds melancholy at every pore—seems frantically unhappy and disoriented. Families disintegrate. The oldest institutions lose cachet and respect. A blur of opinions and viewpoints blinds the sight. Self-absorption and narcissism sink their hooks into the realms of ideas and practice.

Whither? Quo vadis, Domine? The Church was formed and commissioned both to ask and answer such questions, a larger task than Congress or the Supreme Court or the United Nations seems equipped to essay. I note the response of the senior warden of St. Luke’s parish, one Debbie Kollgaard, to the decidedly unpleasant experience of being kicked out of her parish by her spiritual leaders. “I cannot compromise my faith,” she said. “What I have is more important than any property.” When liberals talk with such generous resolution about their stake in the battles ahead, it may be time to take them seriously. Not quite yet. Not while lawyers do the talking for them.

The new age of evangelism—led by whomever or, likelier still, vast numbers of whomevers—will seek to awaken the culture to the old, deep truth of existence. It will explain the human plight and its divinely provided escape hatch in terms so plain it won’t be recognized how un-plain the explanation seemed to the sufferers of late modernity, including those encased in the material wonders of the first decade of the Third Christian Millennium.

It may be remembered, when the time comes, that a once-grand, once-grave old church, the Episcopal Church, conspired as long as possible to keep at bay the architects of the awakening. Or it may not be remembered at all.

Leave a Reply