Fifty-three years ago, in the fall of 1968, I was among a gaggle of idealistic first-year students sitting in a classroom at the Harvard Law School, where a crusty old professor advised us to study international law. In that discipline, “the dew was still on the grass,” he said. In those days, when many budding lawyers thought they wanted to elevate the poor and downtrodden by practicing public interest law, the old professor’s words struck a chord. Surely the rest of the world was slowly coming to the realization that the liberal principles taught at Harvard were inescapably correct. It was only a matter of time before the entire world would be constructed anew—free of poverty, war, and rancor—by elite lawyers like us, trained in international law. Or so we thought.

Thirty-three years later, on Sept. 11, 2001, the Twin Towers fell, struck down by hijacked airliners flown by fanatics with visions of 72 virgins whom they would enjoy in a Muslim Valhalla. At that point, it became harder to believe that reason was all that was necessary to secure international order. Accordingly, instead of contributing to a new international order (although naïve hope for that lingered in some quarters), the creative, elite lawyers in the Bush Administration and the Congress perfected the foundations of the modern surveillance state.

Less than two months after 9/11, the United States Congress passed, and President George W. Bush quickly signed, the “Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001,” otherwise known as “The Patriot Act.” It was sold to legislators and the American people under the reasoning of that great truism, that eternal vigilance is the price of liberty, though in reality the act was a perversion of that principle.

In a series of bold strokes removing former restraints against government surveillance, the new statute gave extra wiretapping and surveillance tools to federal law enforcement, increased information-sharing between law enforcement and intelligence agencies, added financial disclosure and reporting requirements to crack down on terrorist funding, and gave greater authority to the U.S. attorney general to detain and deport foreign nationals suspected of terrorist activity.

The act was passed in an atmosphere of national frenzy with virtually unprecedented speed and little opposition. The House passed it by a vote of 357–66, the Senate by 98–1. As now happens with legislation that is hundreds or even thousands of pages long, it is unlikely that most members of Congress ever read, much less understood, the entire 342-page bill. Not even civil libertarians, left or right, were able to offer much immediate criticism of the Patriot Act, so profound was the perceived threat to national security after 9/11, and so horrific was the loss of life.

One of the most profound consequences of the Patriot Act was the dismantling of the safeguards that had prevented foreign and domestic U.S. intelligence agencies from sharing information about U.S. citizens. The expanding surveillance bureaucracy that resulted was able easily to manipulate the institutional safeguards already in place, such as the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) Court, established in 1978.

The FISA Court was further weakened in the years after the Patriot Act, including by the FISA Amendments Act (FAA) of 2008, which gave the National Security Administration (NSA) “almost unchecked power to monitor Americans’ international phone calls, text messages, and emails—under the guise of targeting foreigners abroad,” according to a brief by the American Civil Liberties Union.

As a result of this increase in surveillance powers, and due to disclosures about these powers from former NSA contractor Edward Snowden and other whistleblowers, we now know that “an unknown number of purely domestic communications are monitored, that the rules that supposedly protect Americans’ privacy are weak and riddled with exceptions, and that virtually every email that goes into or out of the United States is scanned for suspicious keywords,” the ACLU wrote in a position statement on NSA surveillance.

The ACLU’s fear of surveillance abuse was justified. The most egregious example of this abuse on a high-profile person came with the monitoring of President Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign. The FISA Court approved such surveillance based on a dossier of false information about foreign intrigue that came from opposition research by Trump’s political opponents.

Though the Patriot Act was ostensibly targeted at foreign enemies, its provisions allowed for domestic surveillance. This passed muster even with alleged libertarian Richard Posner, a Reagan appointee to the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, one of the most intelligent judges of his era. In his 2006 book, Not a Suicide Pact: The Constitution in a Time of National Emergency, Posner wrote:

Rooting out an invisible enemy in our midst might be fatally inhibited if we felt constrained to strict observance of civil liberties designed in and for eras in which the only serious internal threat (apart from spies) came from common criminals.

Posner went even further, writing in the same book:

I argue that an American version of the British Official Secrets Act may be needed in order to seal leaks of classified material that are harmful to national security or that invade personal privacy, and that such a law would not violate the Constitution.

Although we never received an Official Secrets Act, although some of the Patriot Act’s provisions and some provisions of the FAA have expired, and although there was no further catastrophe on the same scale as 9/11, the habit of domestic surveillance has proved hard to eradicate. In fact, the security state stretched its surveillance powers even beyond the broadened limits of the Patriot Act in the wake of 9/11. President Bush secretly authorized the NSA to eavesdrop on Americans suspected of terrorist activity without obtaining warrants. The Bush administration also detained people indefinitely in military prisons such as Guantanamo Bay, denying them access to lawyers and the courts; Attorney General Alberto Gonzales argued that the president’s war powers gave him such authority.

There was at least one Supreme Court decision and a few lower court decisions that rejected overreach in the “War on Terror,” but clearly many executive branch and agency officials have not felt constrained. Whatever safeguards remain established in the law, overreach in the U.S. national surveillance state is a practical reality in our current government climate.

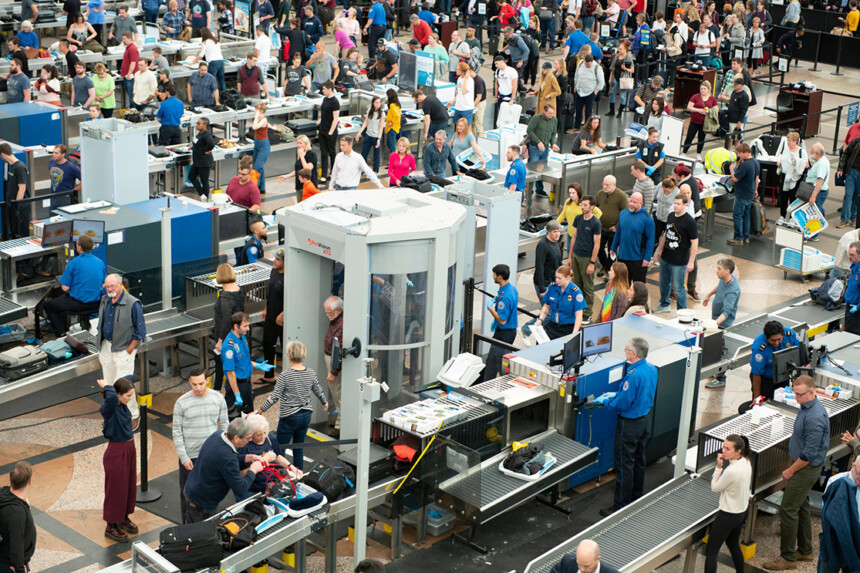

Paralyzed by fear of Islamic terrorism, Americans came to tolerate humiliating personal searches at airports and a high level of regimentation and obedience when traveling domestically and abroad. It is not surprising that this trained passivity paved the way for the draconian lockdowns, mask mandates, and travel restrictions that we are experiencing with the current coronavirus pandemic.

At the same time, the Islamic terrorism threat has been receding. The emergence of a new bin Laden bent on punishing Americans for our Middle East foreign policy is no longer likely, now that the Muslim world has been torn apart by internecine struggle. Foreign terrorism poses far less of a threat to us than it did 20 years ago—and yet the domestic surveillance state it spawned is stronger than ever.

Even the Biden administration probably understands that we are no longer at risk from Muslim terrorists. But the Biden regime is also devoted to keeping the dissident elements of the American population in check by keeping them in fear, and so its spokespersons insist that our greatest threat is from domestic terrorists—particularly white supremacists and Donald Trump supporters. This attitude was demonstrated by New York Times reporter Katie Benner, who tweeted in July that Trump’s supporters should be labeled as “enemies of the state.”

On the contrary, the greatest threats to Americans in our time come externally from the Chinese, and internally from our own Leviathan state.

The recent COVID pandemic has taught us is that our liberty is even more precarious than we thought, and that neither the press nor the courts can be trusted to point out executive, legislative, or administrative abuses of arbitrary power. Indeed, Americans now face an unholy trinity of oligarchic tech companies, the press, and the government. Our ruling class insists it was just “following the science,” but even a cursory review of the actual data demonstrates that there was no consensus among scientists, and that the imposed lockdowns and mask mandates were mostly ineffective in stopping the spread of the virus.

above: Members of the congregation keep social distancing during the Ash Wednesday service at Sacred Heart Church in Haworth, New Jersey on Feb. 17, 2021. (© Mitsu Yasukawa/Northjersey.com via Imagn Content Services, LLC)

I suspect the COVID measures may have been only a dress rehearsal for even more draconian sacrifices to be enforced in the name of preventing harmful climate change.

It may be time for a return to American common sense. Perhaps the first position to which we should return is that more regulation and legislation are not panaceas for American problems. Not for nothing did one of our most distinguished federal judges, Richard Peters of Pennsylvania, write in the late 18th century that statutes rarely improved on the sensible common-law rules followed by English and American courts for centuries.

It is not at all clear that the federal bureaucracy with its authorizing statutes and Byzantine Code of Federal Regulations has improved life in our country, except for bureaucrats and their beneficiaries. If Thomas Jefferson was correct that the government that governs best is the one closest to the people, then there can be no basis for the federal COVID impositions, Obamacare, or indeed the entire apparatus of the Administrative State.

Just as Islamic terrorism may have never been an existential threat justifying the growth of federal authoritarian government, the same is true of climate change and the coronavirus. The real existential threat facing this nation is the death of the constitutional protection provided by federalism, which is the concept that the central government ought to exercise clearly limited and enumerated powers, with primary legislative authority lodged in state and local governments.

The threat is also in the erosion of structural checks and balances inherent in the concept of separation of powers; in other words, that only legislatures should make new laws, executives should merely follow the law, and judges should merely enforce it. The progressives and liberals in the law schools for the last seven decades took the Warren Court as their model for activist judges who remade the Constitution, taking away from the American people their right to self-government.

Roe v. Wade, finding in the Constitution a nonexistent right to abortion, and Obergefell v. Hodges, similarly discovering a previously hidden right to same-sex marriage, are only the most blatant and bizarre examples of this arbitrary judicial power. An inventive judiciary rides roughshod over the separation of powers and makes up new law to accord with social fashion.

The judiciary no longer feels bound by the Constitution. Meanwhile, the legislative branch is stymied by incomprehensible legislation, such as the 2,700-page, $1 trillion infrastructure bill, which no member of the Senate has likely read, but which passed in mid-August. Given the disorder in the judicial and legislative branches, is it any surprise that an arbitrary federal bureaucracy does what it wants?

Passivity is an incentive for governmental abuse. Coupled with the expansion of prosecutorial discretion, America now has a two-tiered justice system. In this system, the politically favored escape prosecution, as was the good fortune of Hillary Clinton and James Clapper, while the politically powerless, such as the Jan. 6 protesters, linger in confinement, deprived of their constitutionally protected rights.

Many of us who supported the Trump administration believe that we have seen the truth of the adage that it’s not who votes that counts, but rather who counts the votes. Similarly, and equally horrifying, we’ve learned that it may not matter what the Constitution or statutes provide, it’s who staffs the law enforcement and intelligence agencies that determines whether America maintains any semblance of the rule of law.

With the Constitutional restraints of separation of powers and federalism in shambles, and with doubts about whether the franchise is honestly enforced, it seems quaint to worry about national security statutory schemes, when popular sovereignty itself is so clearly endangered.

Ivan Karamazov in Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov famously observed that if God does not exist, everything is permitted. John Adams asserted that the American Constitution was fit only for a religious people, and our Federalist framers were uniform in their belief that only a virtuous citizenry could maintain our republic. The 1776 Pennsylvania Constitution, the most democratic of the early state charters, expressly provided that only legislators who took an oath to a deity who rewarded the good and punished the wicked could serve.

No such requirement has prevailed in this country since the early 19th century. Indeed, formal religion is today removed from the American public square, and the Supreme Court’s misconceived Establishment Clause jurisprudence has banned religious instruction from the public schools and from all but a few of our public ceremonies and celebrations.

Our civic life and culture is now shaped instead by selfish individualism, not fear of divine judgment. We live in an era when even the Supreme Court can declare, as it did in the 1992 Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision: “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.”

Americans once understood that self-actualization was not all there was to life, and that a virtuous citizen not only possessed God-given rights, but also duties to God, to country, and to fellow Americans. We thought the way to secure those rights, and ensure the performance of those duties, was to create a Constitution that rested on the sovereignty of the American people. Popular sovereignty, informed with moral virtue and a sense of legality, would restrain arbitrary power. It would guarantee the freedom to pursue economic progress and social mobility and to carve out a sphere of private life immune from governmental interference.

There was, of course, some tension and inconsistency in these goals, but they existed, more or less in harmony, for two centuries.

Our greatest peril today may not even come from the collapse of the constitutional and legal structure and the growth of an oppressive surveillance state, but from the disappearance of civic virtue, without which a legal framework cannot be sustained. The choice before us is whether we will somehow recapture that virtue and begin dismantling the corrupt and lawless federal bureaucracy, or whether we will continue to submit to despotism.

Image Credit:

above: a stream of travelers is screened by TSA at Denver International Airport (American Photo Archive / Alamy Stock Photo)

Leave a Reply