“We are exceptional people; we are among those nations that . . .

exist only to give the world some terrible lesson.”

—Pyotr Chaadayev

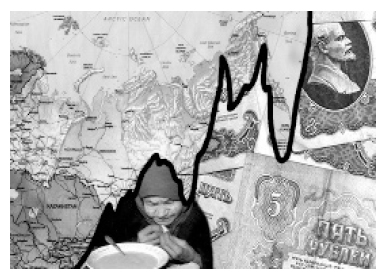

Chaadayev’s words came to mind in the aftermath of a blizzard in Vladivostok, snowy peaks ringing the port city, the sky still obscured by thick clouds. It was November 1992. The Soviet Union had collapsed under the weight of the communist legacy, a surge of nationalism, and the fall of the price of oil in the 80’s, depriving the party gerontocracy of the cash that had kept it on a kind of life support for years.

The failed August 1991 coup had accelerated the moving collapse that had started during the hopeful years of perestroika and glasnost, and the hope had been lost, swept away by popular disappointment with the results. I had watched the first—and last—Soviet president on TV after the wretched coup leaders were arrested, half amused and half appalled, pitying the man. He just didn’t get it: The Soviet Union was over and done with. What followed was the chaos one would expect from such a collapse, though it could have been much worse. Travelers were stranded across Russia because of fuel shortages and equipment breakdowns, factories were closing or operating on short hours, pay arrears were mounting, the people were losing work and their psychological bearings. What is it like to have one’s country and all the ideological and emotional underpinnings that supported it simply disappear in an historical instant?

The power grid in Vladivostok was down, knocked out by a blizzard shortly after my arrival from Japan. Public transportation had halted because of the freeze, and there was no heat anywhere except for the fires that burned in the stoves of wooden houses in the dilapidated city. Vladivostok was in danger of being partially dismantled by its inhabitants, and the militia was ordered to arrest those tearing down fences and other wooden structures, dragging the fuel for their fires on sleds through the freezing city.

I slept bundled up in my coat and fur hat, complete with boots, in a hotel hanging on a ledge over the bay patrolled by Afghan veterans toting Kalashnikovs. The lobby and restaurant were packed with a collection of shady gangland figures of various nationalities—Korean, Chinese, Russian, gypsies. The prostitutes who packed the bar followed any prosperous-looking guests, hoping to earn some foreign currency, as the ruble was now all but worthless. It paid to be cautious: A Japanese businessman intent on expanding into this “emerging market” had been kidnapped; a couple of his fingers were returned to his associates along with a ransom note and a threat to return other body parts if the payment wasn’t made.

Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign had ended in failure, and I could step around the results of the Russian habit of drinking to oblivion on the streets of the frozen city: a corpse of a drunk who had died from exposure, then two bloody bodies left by a drunk driver who had attempted to make his way in the foul weather.

A few had taken refuge from the cold in an Orthodox church that was being restored by some interested locals, and I joined them. There were even some young people at church. There was hope amid the ruins—hope that would, as in the past, be disappointed. But life goes on. My encounters with the Russians over the years have taught me that even in the darkest hour people can go on laughing, socializing, believing, and enjoying life. Russian believers are few (communism’s militant atheism did its job), but I have always found them, especially those who suffered for their faith in the Soviet period, to be among the most tranquil and courageous people I have ever met.

There are many lessons to be learned from Russia’s mistakes during this period, but there are also some positives in the Russian experience that might help Americans through our own economic, social, and political crisis.

Russia bounced back economically after the ruble collapsed in 1998 (at a time when oil was below ten dollars per barrel); the devaluation eventually made Russian industry more competitive. The policy of accumulating reserves, which rapidly piled up as oil prices rose in recent years, enabled Moscow to do things that have kept the ship of state afloat (thus far, at least) despite the onset of the latest global crisis. The reserves were wisely used to pay down the state’s foreign debt. A measure of fiscal prudence kept reserves from being spent (as so many wished to do), and those reserves have been used to save the Russian banking and financial system from collapse.

These fiscal policies were steadfastly supported by Vladimir Putin as both president and premier, and by his current finance minister, Aleksey Kudrin. They deserve a measure of credit for that, and their fiscal restraint and prudence provide a lesson for us. The state’s policy, however, did have a downside, which brings us back to Russia’s lessons on what not to do: Credit on the scale that the industrial magnates wanted was scarce at home, and industry had to look abroad for money. The Putin/Kudrin policy was a deal with the “oligarchs”; the state would pay off foreign debt, and industrial credits would be hard to come by at home, but the oligarchs could borrow abroad. And so they did, often with the same sort of reckless abandon we have seen in our own borrow-and-spend culture, using the debt largely for expansion and not for rebuilding the country’s aging industrial infrastructure, or for developing such critical sectors as housing. Consequently, corporate debts in Russia are threateningly huge, and the specter of another default, this time by Russian industry, looms on the horizon. At the same time, the state encouraged consumer spending (and borrowing) to help ensure political and social stability.

America has opted for a dangerous borrow-and-spend policy, while offshoring industry. Russia, on the other hand, has skipped modernization and sector-development in favor of oil/energy dependence and corporate debt, coupled with her own version of a consumer binge. Is either country capable of shifting her economic paradigm? Is Russia’s recent past our future?

State atheism was a devastating blow to the spiritual and moral health of Russia—a blow from which I now doubt she will ever recover. For a time, Soviet ideology replaced Christianity as the motive force for many; now, in its place, lies a moral and spiritual void. When utopian dreams of a bright future burned out in the bloodbath of revolution, civil war, mass terror, and world war, Russia was exhausted, and her belief in any future, any cause other than immediate material needs, seriously eroded. Dangerous demographic and social trends were accelerated by the Soviet collapse.

In their article “Putin’s Third Way” (National Interest, January 6) Clifford G. Gaddy and Barry W. Ickes point out that, demographically, Russia is still in free fall. Despite a slight increase in birthrates over the past few years (attributable, perhaps, to higher incomes, which are now falling), mortality rates, especially for males, are nothing short of catastrophic: Russia’s population shrank 13-percent faster under Putin than under his predecessor. The state has done nothing to combat alcoholism, and alcohol consumption per capita, which was already sky high, is up by 29 percent over the past decade. According to Gaddy and Ickes, the Russian government “promoted consumption today at the expense of investment for tomorrow,” a strategy that may sound familiar to Americans. The characteristic Russian fatalism, however, is now more prevalent than ever, likely the result of a spiritual malaise.

Nicholas Eberstadt, writing in World Affairs Journal (“Drunken Nation: Russia’s Depopulation Bomb”), called Russia’s current condition “katastroika” and wrote of “the withering away of the family itself,” as marriage declines, divorce rates continue to rise, and parents forsake their children. (According to Eberstadt’s calculations, roughly seven percent of Russia’s children have been abandoned.) The rate of violent and accidental deaths is stunning. Eberstadt doesn’t even mention abortions (which, according to most recent studies, outpace live births) but writes that Russia “has pioneered a unique new profile of mass debilitation and foreshortened life previously unknown in all of human history.”

Many of the pathologies exhibited by the Russians are prevalent in the United States as well. Nonetheless, perceptive observers would recognize America as a much healthier place than Russia, healthier physically and spiritually, though secularism and outright hostility to Christianity are on the march here. Respect for law has eroded. (Has the behavior of our own political and Wall Street elite differed all that much from that of Russia’s oligarchs? And the Obama administration’s handling of the Chrysler restructuring has investors worried about the kind of political risks usually associated with places like Russia.) The family is in decline. Social involvement is dropping. (Recall the stir that sociologist Robert Putnam’s research on declining civic engagement caused in recent years.) Yet a sense of civic duty is still widespread. Volunteerism is still common. (The Soviets did a thorough job of destroying private initiative, and the kind of civic involvement we see in America is not common in Russia.) Church attendance is high relative to the rest of the developed world. And patriotism is still important in “fly-over country.” If we want to salvage our country, then preserving these aspects of American life is critical.

The Soviet Union was a multicultural empire, and nationalism played a huge role in its collapse. Only a brutal authoritarian system could hold this diverse empire together and suppress ethnic conflict. When the will to use brute force declined, the empire fell apart, and chaos followed. Robert Putnam has also pointed out (much to his own distress) that increased “diversity”—driven by mass immigration—spurs on a decline in civic engagement and social trust, two factors that are critical for maintaining any free society, not to mention the social cohesion needed to avoid fragmentation and collapse. Globalism has not really made Russia, a classic “low trust” society (or any other postcommunist or Third World country) more like us. Diversity is making us more like them.

Still, we should not abandon hope. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn lived to see the end of communist rule. Unfortunately for Russia, it came too late to revive the nation. In this regard, we may fare better than the Russians. If communism can fall, so can managerial, multicultural capitalism. The katastroika that is today’s Russia is the result of a failed communist version of modernization, but the West has been moving in a similar direction by a different path. We should watch, learn, and hope that something good can be salvaged from our own economic and social crisis. When it comes time to pick up the pieces, we may have more to work with than the Russians did.

Leave a Reply