Contrary to the assertion of official historians, April 1865, which saw the fall of the Confederate States of America, was not the month in which the “Union” was saved or a “nation” was forged. It was the month that saw the transformation of the republic into an oligarchy, and the expansion of government subsidies into military Keynesianism. War, as the Founding Fathers warned, was the midwife.

The late Chalmers Johnson defined military Keynesianism as

the mistaken belief that public policies focused on frequent wars, huge expenditures on weapons and munitions, and large standing armies can indefinitely sustain a wealthy capitalist economy. The opposite is actually true.

Such a policy, directly or indirectly, enriches select politicians and businesses.

Lincoln employed the war of 1861-65 to increase the tariff and restore the repudiated system of internal improvements. Both endeavors transferred public money to private companies with political connections under a pretext of national security. The tariff was declared necessary to ensure political independence by securing economic independence for the United States from foreign suppliers, in particular the British. Internal improvements—the building of roads, railroads, turnpikes, ports, and canals by private firms with public funds—were declared essential to enhance commerce and defense, even though projects were often never completed and the funds frequently embezzled.

Implementing these policies required that four fundamental changes be made to the structure of the United States, which Lincoln was able to achieve under the cover of war.

The political system was converted into an oligarchy, an alliance of federal politicians (originally from the Republican Party) and business interests (originally from Northern states). The initial focus was on the railroads.

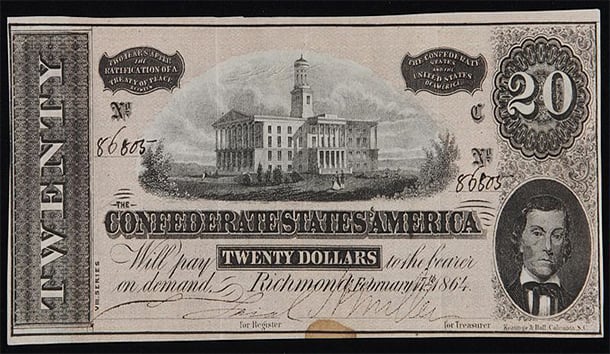

Through the Legal Tender Act of 1862 and the National Currency Acts of 1863 and 1864, the currency was “nationalized.” Violating Article I, Section 10, of the U.S. Constitution, which mandated currency be of gold and silver coin, Lincoln issued paper money dubbed “greenbacks.” This new currency could not be immediately redeemed in either metal by citizens, which created, in effect, a two-tier legal system: one for citizens, the other for banks. While debtors were required by law to pay their creditors, under Lincoln banks, central to financing the oligarchy, were not. Banks could legally refuse to redeem Lincoln’s greenbacks in gold or silver and continue to operate without penalty. This new money for the new economy enabled the government to promote a patronage system with select businesses.

Lincoln circumscribed the Bill of Rights, suppressing the First (“Freedom of Speech, Press, Religion and Petition”), Fourth (“Right of Search and Seizure regulated”), Fifth (“Provisions Concerning Prosecution”), Sixth (“Right to a Speedy Trial, witnesses, etc.”), Seventh (“Right to a Trial by Jury”), and Eighth (“Excessive bail, cruel punishment”) Amendments. He did so by claiming extraordinary powers as commander in chief, establishing extraconstitutional precedents that would be exercised by his successors—launching wars without congressional authorization, ignoring international treaties, targeting civilians, initiating warrantless searches, denying habeas corpus, imposing indefinite detention, fabricating “law” through executive decisions, and declaring that the courts have no jurisdiction to review or judge presidential acts in “wartime.” These acts were, and are, done in the name of national security.

But as Benjamin Franklin noted, “anyone who trades liberty for security deserves neither liberty nor security.” And as James Madison repeatedly warned, it is in the name of protecting liberty from a foreign threat that constitutional rights are suppressed.

In a speech at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Madison cautioned,

In time of actual war, great discretionary powers are constantly given to the Executive Magistrate. Constant apprehension of War, has the same tendency to render the head too large for the body. A standing military force, with an overgrown Executive will not long be safe companions to liberty. The means of defence [against] foreign danger, have been always the instruments of tyranny at home. Among the Romans it was a standing maxim to excite a war, whenever a revolt was apprehended. Throughout all Europe, the armies kept up under the pretext of defending, have enslaved the people.

The next year, at the Virginia Convention to ratify the Constitution, Madison admonished his fellow legislators,

Since the general civilization of mankind, I believe there are more instances of the abridgment of the freedom of the people by gradual and silent encroachments of those in power, than by violent and sudden usurpations.

In 1795, Madison wrote perhaps his most famous dictum:

Of all the enemies to public liberty war is, perhaps, the most to be dreaded, because it comprises and develops the germ of every other. War is the parent of armies; from these proceed debts and taxes; and armies, and debts, and taxes are the known instruments for bringing the many under the domination of the few. In war, too, the discretionary power of the Executive is extended; its influence in dealing out offices, honors, and emoluments is multiplied; and all the means of seducing the minds, are added to those of subduing the force, of the people. The same malignant aspect in republicanism may be traced in the inequality of fortunes, and the opportunities of fraud, growing out of a state of war, and in the degeneracy of manners and of morals engendered by both. No nation could preserve its freedom in the midst of continual warfare.

In a 1798 letter to Thomas Jefferson, Madison repeated his concerns: “Perhaps it is a universal truth that the loss of liberty at home is to be charged against provisions against danger, real or pretended from abroad.”

But Madison was America’s Cassandra. He correctly predicted the future, but no one would believe him. This political myopia enabled Lincoln to use the war to install a Republican Party dictatorship on the federal government that endured for a quarter of a century. The party represented Northern businessmen who had profited from the war and its aftermath, such as Andrew Carnegie, J. Pierpont Morgan, and John D. Rockefeller, including (in the words of historian Dee Brown) “a dynasty of American families . . . Brewsters, Bushnells, Olcotts, Harkers, Harrisons, Trowbridges, Langworthys, Reids, Ogdens, Bradfords, Noyeses, Brooks, Cornells, and dozens of others.” For their continued enrichment, the dictatorship had to be maintained. This was accomplished through a series of elections that were neither free nor fair. The most notorious was the 1876 presidential election, in which the Republican Party had its candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, who had lost both the popular vote and in the Electoral College, declared the winner.

One of the first acts of President Hayes was to uphold the financial interests of the oligarchy by ordering U.S. troops to suppress the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Also known as the Great Upheaval, it engulfed 14 states, including West Virginia, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Missouri. Among the centers of the strikes were Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Toledo, Louisville, Buffalo, and San Francisco. Strikers protested against poor working conditions and a second ten percent cut in eight months in their already low wages. Originally, a strike by 100,000 railroad workers, it grew in St. Louis into a general strike joined by laborers from other industries. As reported in the St. Louis Republican,

Strikes were occurring almost every hour. The great State of Pennsylvania was in an uproar; New Jersey was afflicted by a paralysing dread; New York was mustering an army of militia; Ohio was shaken from Lake Erie to the Ohio River; Indiana rested in a dreadful suspense. Illinois, and especially its great metropolis, Chicago, apparently hung on the verge of a vortex of confusion and tumult. St. Louis had already felt the effect of the premonitory shocks of the uprising.

This decline in the standard of living of American workers resulted from repercussions of the depression known as the Panic of 1873, which lasted until 1879. It was a consequence of Lincoln’s new economy of speculative finance and paper money and had resulted from the dealings of one of the leading banking firms, Jay Cooke & Co., the Northern Pacific Railroad, and the U.S. government. Ten states and 18,000 businesses went bankrupt. Unemployment reached 14 percent. The strike, which had started on July 16, was crushed by U.S. troops on August 2.

The relative ease by which the oligarchy had acquired its fortune in the Civil War and its ability to have U.S. troops protect its financial interests led to the emergence of military Keynesianism. Mark Twain dubbed it the “Gilded Age,” which he described in “The Revised Catechism”: “What is the chief end of man?—to get rich. In what way?—dishonestly if we can; honestly if we must.” Such moneymaking became a bipartisan policy as the oligarchy was broadened to include Democrats.

The Civil War and Reconstruction were followed by more military adventures on the part of the U.S. government to advance various U.S. business interests. These included the Plains Indians War (1861-90) for the railroads; the Hawaiian Islands (1893) for the sugar industry; the Spanish-American War (1898); the Philippine Islands (1899-1913); Cuba, Haiti, Mexico, Panama, and Central America (1895-1913) for the banks, the oil industry, and agriculture interests.

With the inauguration in 1913 of Democratic President Woodrow Wilson, the Progressive Era arrived. As president of Princeton University, Wilson wrote a succinct justification for the military Keynesianism he would follow as President of the United States:

Since trade ignores national boundaries and the manufacturer insists on having the world as a market, the flag of his nation must follow him, and the doors of the nations which are closed against him must be battered down. Concessions obtained by financiers must be safeguarded by ministers of state, even if the sovereignty of unwilling nations be outraged in the process.

With Wilson even the pretense of constitutional government was discarded. He proclaimed a need to abolish a federal government of checks and balances:

It is, therefore, manifestly a radical defect in our federal system that it parcels out power and confuses responsibility as it does. The main purpose of the Convention of 1787 seems to have been to accomplish this grievous mistake. The “literary theory” of checks and balances is simply a consistent account of what our Constitution makers tried to do; and those checks and balances have proved mischievous just to the extent which they have succeeded in establishing themselves.

In its place, Wilson advocated an imperial presidency “as big as and as influential as the man who occupies it,” which, in turn, would facilitate his policy of military Keynesianism by allowing him to dispatch U.S. troops overseas on any pretext.

While Wilson is cited as having kept the United States out of war in his first term, the reference is only to World War I. The business of war defined all eight years of his administration. Under Wilson, the United States was virtually in a constant state of war in the Caribbean, Latin America, or the Pacific. Although a Democrat, Wilson was a faithful disciple of Abraham Lincoln on the issue of war: Never admit it is for the benefit of special interests, but declare that it is for some noble cause, and thereby fix “the public gaze upon the exceeding brightness of military glory.”

Maj. Gen. Smedley Butler, one of the most distinguished and decorated Marines in U.S. history, explained the nature of the oligarchy and military Keynesianism in his famous 1933 speech:

War is just a racket. A racket is best described, I believe, as something that is not what it seems to the majority of people. Only a small inside group knows what it is about. It is conducted for the benefit of the very few at the expense of the masses.

I believe in adequate defense at the coastline and nothing else. If a nation comes over here to fight, then we’ll fight. The trouble with America is that when the dollar only earns 6 percent over here, then it gets restless and goes overseas to get 100 percent. Then the flag follows the dollar and the soldiers follow the flag. . . .

I helped make Mexico, especially Tampico, safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefits of Wall Street. . . . I helped purify Nicaragua for the international banking house of Brown Brothers in 1909-1912. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for American sugar interests in 1916. In China I helped to see to it that Standard Oil went its way unmolested.

During those years, I had, as the boys in the back room would say, a swell racket. Looking back on it, I feel that I could have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was to operate his racket in three districts. I operated on three continents.

World War I established the precedent of using military Keynesianism on a grand scale to rescue the oligarchic economy from an economic downturn, the recession of 1914, and then sustain the resulting economic growth. Despite official neutrality, bankers and industrialists such as Du Pont, General Electric, General Motors, U.S. Steel, and Westinghouse, plus speculators, with the approval of Wilson, favored the Allies to whom they extended credits and loans in amounts 85 times greater than those to Germany. By 1917, the Allies owed American businesses seven billion dollars.

According to historian Barbara Tuchman, “Eventually, the United States became the larder, arsenal, and bank of the Allies and acquired a direct interest in Allied victory.” If the Allies were militarily defeated or forced to accept a negotiated political settlement, they could not repay their loans. The boom would go bust, not just for the lending institutions, but for the U.S. economy as well. The result would likely be not a repetition of the recession of 1914, but a severe depression. The U.S. government entered the war to prevent that possibility by ensuring the military defeat of Germany and, with it, the reimbursement of American businesses from war reparations that would be imposed on Germany and eventually total $33 billion.

In 1936, the Senate’s Report of the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry (the Nye Report) stated that the “committee and its members have said again and again, that it was war trade and the war boom . . . that played the primary part in moving the United States into war.” President Wilson was “caught up in a situation created largely by the profit-making interests in the United States . . . ”

As General Butler observed, “At least 21,000 new millionaires and billionaires were made in the United States during the World War.”

Wilson’s policy of military Keynesianism realized two goals: to grow the economy out of recession, and to preserve the oligarchy to ensure political and social stability. That success, however, was short-lived. The economic boom their policies created lasted over a decade, but then collapsed in 1929, ushering in the Great Depression.

At its worst, unemployment during the Great Depression reached 25 percent. But after seven years of New Deal government programs, unemployment in 1940 still remained at 15 percent—ominously higher than during the social unrest of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. With World War II raging in Europe, President Franklin Roosevelt resorted to military Keynesianism to grow the economy out of depression. At first, as with Wilson, it was done indirectly, by supplying the Allies with war materiel under Lend-Lease. Eventually, as with Wilson, the United States entered the war. The country emerged from the conflict with a powerful economy, nearly full employment, and as one of two superpowers in a world devastated by war and divided into two hostile ideological camps.

With the population of the United States still traumatized by the experience of the Great Depression and fearful of its return, the start of the Cold War in 1945 enabled military Keynesianism to remain a key component of the U.S. economy. As National Security Council Report 68, signed by President Harry Truman on September 30, 1950, explained,

One of the most significant lessons of our World War II experience was that the American economy, when it operates at a level approaching full efficiency, can provide enormous resources for purposes other than civilian consumption while simultaneously providing a high standard of living.

Maintaining that economy required only that Truman and his successors follow the advice of U.S. Sen. Arthur Vandenberg: “scare the hell out of the American people” about foreign threats to justify such spending.

The Cold War ended, but the anticipated “peace dividend” never materialized because the fear tactic of Vandenberg was never abandoned. Instead, military Keynesianism expands to meet perpetual threats, as a host of new enemies constantly appear, and old enemies, like Banquo’s ghost, return—international drug cartels, Serbian nationalists, China, Al Qaeda, the Taliban, Iraq, North Korea, Iran, Russia, jihadists, Somalia, Libya, Syria, Mali . . .

To defeat these and future enemies, the world has been partitioned into six military commands—USNORTHCOM, for North America; USSOUTHCOM, for the Caribbean, Central, and South America; USEUCOM, for Europe and Russia; USCENTCOM, for the Middle East and Central Asia; USPACOM, for the rest of Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific; and USAFRICOM, for all of Africa except Egypt.

In a report released in 2007 by the Center for Economic and Policy Research, a Washington, D.C., think tank, economist Dean Baker described the self-defeating nature of military Keynesianism:

It is often believed that wars and military spending increases are good for the economy. In fact, most economic models show that military spending diverts resources from productive uses, such as consumption and investment, and ultimately slows economic growth and reduces employment.

Add to the diversion of financial resources the country’s old and decrepit infrastructure, the continued hollowing out of the country’s industrial base, a currency that most likely does not possess gold reserves to back the paper money in circulation, and an $11 trillion debt representing 73 percent of GDP, and we can clearly see that military Keynesianism is unsustainable.

Unless Lincoln’s legacy of military Keynesianism is abandoned, the economic and political future of the United States is bleak. As Chalmers Johnson warned, that future could be defined by “national insolvency and a long depression.”

Leave a Reply