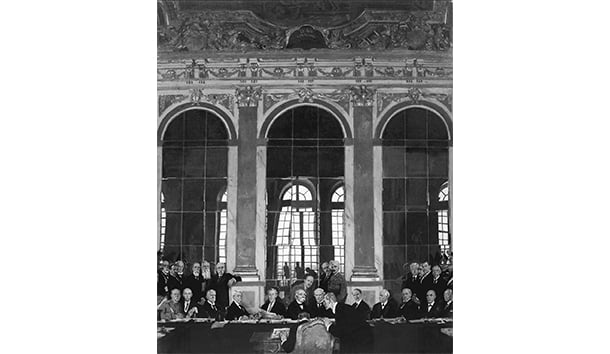

The Paris Peace Conference opened at the Palace of Versailles 100 years ago (January 18, 1919). It was the most ambitious gathering of its kind in history: Leaders and diplomats of 27 nations convened to shape the future, a mere ten weeks after the Armistice. Far from reestablishing order in Europe and the world after over four years of unprecedented carnage and destruction, however, it produced a flawed treaty that contained the seeds of another, even more destructive war a generation later.

A major weakness of the Versailles system was that two great European powers were not present. Germany and her allies were excluded until after the details of all the peace treaties had been agreed upon by the Big Four—France, Britain, the United States, and Italy—and presented as faits accomplis to each of them separately. Russia was not invited because the Bolsheviks had signed their separate peace with the Central Powers at Brest-Litovsk in March 1918.

Brest-Litovsk was an important precursor of Versailles. Ludendorff’s generals had formulated extremely harsh terms that were seen as excessive even by the German civilian negotiators. This convinced the Entente powers that no reasonable agreement could be reached with Germany, and that they had to fight for an outright victory. By imposing a Carthaginian peace on Russia, the Germans ensured that they could not count on anyone’s lenience when things went wrong for them. When they later complained that Versailles was too harsh, the Allies could point out that it was in fact far less brutal than the terms imposed on Russia.

When the German army finally gave up in 1918 (the stab-in-the-back myth notwithstanding), what with the Kaiser abdicating and the Armistice signed, many Germans hoped that they would be treated as Bourbon France was treated in Vienna in 1815, where Talleyrand was a key player. This was not to be. Germany’s egregious behavior before and during the war, including the execution of thousands of French and Belgian civilians, the introduction of poison gas, unrestricted submarine warfare, and the comprehensive destruction of occupied areas in the east and west alike, made a peace of reconciliation politically impossible.

This applied to France in particular. In the end President Raymond Poincaré and Prime Minister Georges (“le Tigre”) Clemenceau got a treaty—having overcome Woodrow Wilson’s and Lloyd George’s objections—which was harsh in appearance but untenable in grand-strategic terms. Germany lost some 13 percent of territory including the Baltic corridor to Poland, an intolerable injustice to most Germans. Yet the country remained unified, unoccupied, and the most powerful European economy, second only to the United States in the world.

The French demanded and got the bulk of 132 billion gold marks (500 billion in today’s dollars), which Germany was ordered to pay in reparations to cover civilian damage caused during the war. There was an insoluble snag, though: To pay the enormous bill, the German economy would have to remain powerful and be allowed to grow, which the French regarded as a calamity. In the end, between 1919 and 1932, Germany paid less than one sixth of that sum. The ink was barely dry on the final treaty when its long-term consequences were forecast with prophetic precision by John Maynard Keynes in The Economic Consequences of the Peace.

It is an additional irony of Versailles that the settlements eventually proved to be a source of weakness for those who appeared to have gained the most. Resurrected Poland’s lands east of the Curzon Line and her corridor to the Baltic which cut Germany in two, Czechoslovakia’s possession of the Sudetenland with its three-and-a-half million Germans, Rumania’s doubling in size in the mostly Magyar lands, and the formation of Yugoslavia with its many minorities, created a constant source of revanchist malevolence among the losers. They could argue, with reason, that many of these arrangements—and notably the corridor—violated the principle of self-determination heralded in Wilson’s Fourteen Points. Eventually, they exacted their revenge, starting with Munich less than two decades later.

A century after Versailles, and eight decades after the system based upon that flawed treaty collapsed, the world needs order more than ever. Not the order of “benevolent global hegemony” based on the full-spectrum dominance of the United States, but an order—possible and necessary—which would be based on a multilateral balance-of-power system that accepts each key player as both legitimate and permanent. Of course this is the exact opposite of the relentless Russophobic expansion of NATO, the promotion of color-coded revolutions, and the many wars in the Middle East that have had disastrous consequences for the countries concerned and for the rationally articulated American interest.

The phenomenon of Western civilizational weakness—as manifested in its demographic crisis and ongoing immigrant invasion, which are both geopolitical and cultural threats of the highest order—were not on the agenda at Versailles, although the root causes of the rot were visible even before the catastrophe of 1914. Indeed, the realities of the early 20th century may provide but a limited guidance for the many challenges we face in the 21st. What remains is the longing for “order” anchored in an earlier, more polished age, an age incompatible with the chaos, brutality, and cultural and civilizational collapse that characterize the one in which we live.

Leave a Reply