On even-numbered years, particularly the ones coinciding with a presidential midterm, my Deep South home county undergoes the grotesque onslaught of local elections. For a few months in the spring and summer (and also in the fall, although this is tempered somewhat by Alabama being a “Red State,” which usually means the winner of the Republican primary takes all), we swat mosquitoes, cut grass, host and attend barbecues, and wade through oceans of self-promoting politicians and their signs, ads, bluster, and egos.

The office seekers and office maintainers scour highways and county roads, looking for a pristine spot of lush green hillside at a busy intersection to impale the ground with their campaign signs. (Obviously, the bigger, the better.) They geographically color-coordinate their signs to correspond with that area’s high-school team colors. That way each community knows that said candidate supports their Wildcats or their Cubs or their Tigers or whatever else they hold dear that might persuade those particular citizens to vote for the candidate.

The public presence of the candidates ratchets higher along with the temperature, the sale of ice cream, and the crime statistics. It becomes unsafe for the average citizen to venture out, as the vultures and their minions haunt the parking lots, the entryways, the exits, the foyers, the stands of athletic events, the bread store, the red lights, the hardware stores, the parks, the malls. They are quick with a handshake, a plastic smile, and a handy card, flyer, or trifold pamphlet with bullet points on why your life will be so much better with them in office.

In my county, we have a commissioner who first was elected in 1994. In a striking example of life imitating art, he bears an uncanny resemblance to that icon of small-town cronyism, the character J.D. “Boss” Hogg from The Dukes of Hazzard. The commissioner’s name is J.D. Hess. Some locals have even begun referring to him as “J.D. ‘Boss’ Hesshogg.” This year, he faced a strong challenger in the Republican primary, and his sense of frantic desperation was palpable. Among his acts of impetuosity in the weeks leading up to the runoff in July was giving away free gasoline cards to people who would share his reelection banner on their Facebook pages. It paid off—he survived the challenge by a couple of hundred votes before returning to hibernation.

For nine years, I served as a deputy sheriff in my county. By law, the county sheriff is responsible for “security” at the polling places. Usually, this would involve periodic checks and answering requests for service. However, when the sheriff himself had an opponent on the ballot, he deemed the need for “security” to be at an especially towering level. Deputies were called in to work overtime, and the sheriff assembled a team of deputies and political friends he considered most loyal, whose only job was constantly to “patrol” the polling places (in the sheriff cars, which had the incumbent’s name emblazoned on each side), ensuring that the integrity of the voting process was protected and everyone felt “safe.” I suppose it would be cynical of anyone to wonder why this heightened need for polling-place security only occurred during the elections wherein the sheriff faced a challenger.

In Alabama, judges are popularly elected. However, their campaigns are restrained by the rules of the Canon of Judicial Ethics. For example, a candidate is prohibited from expressing anything negative about a sitting judge. So the challenger has the task of trying to explain to voters why he or she would make a better judge without addressing specifics. According to the Canon, candidates cannot make any promise of conduct in office other than to fulfill their duties faithfully. For many years I was an active member of our local Fraternal Order of Police lodge, and we would host candidates for office. Each event amounted to an opportunity to hear the candidate say, “I promise I’ll be a good judge.” Canon constraints translate into campaign commercials which tell us that, if elected, the judge will uphold “Alabama values.”

The local candidate is a peculiar species. He or she usually has a life cycle that spans four or six years, regenerating and reappearing at the beginning of each campaign season. Immediately after the election, the candidate goes into somewhat reclusive hiding, only to emerge again at the beginning of a new cycle, reenergized with a zealous spirit and invigorated at the prospect of an additional set of years reclining at the public teat. The only thing more terrifying to the incumbent than a strong challenger is the threat of term limits.

How did we get here? In the early days of the republic, the idea of a man actively and publicly campaigning for himself was considered ungentlemanly. True, in the days of Jefferson and Adams, there was as much mudslinging as there is today, but rarely could it be easily traced to the candidate himself. And it was extremely unbecoming to see the candidate behaving in any manner that would be considered self-promoting.

But now, the slightest semblance of humility is ballot-box poison to a political campaigner. Social media only intensifies this display, with candidates posting endless selfies. We are inundated with pictures of candidates smiling with their families, shooting guns, talking with police, talking with “concerned citizens” over steaming cups of coffee at the local diner, holding babies, holding hands, holding kittens, standing in front of the flag, talking with judges, talking with other famous politicians, walking up the steps of a church—on and on, ad nauseam.

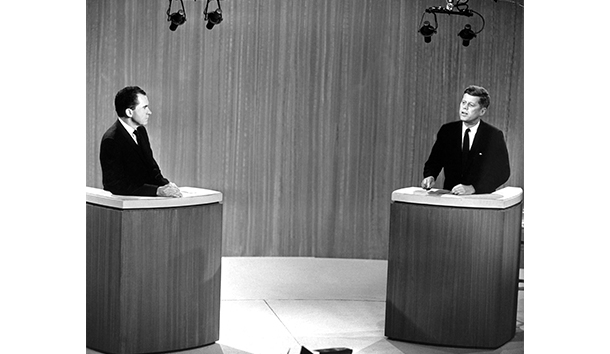

Trying to put a finger on any precise moment when style and appearance took primacy over intelligence and substance is difficult. Technology and television have certainly contributed. One cannot help but consider 1960 and what turned the tide in the tight contest between the two presidential contenders, Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy. As Patrick Buchanan chronicled in The Greatest Comeback,

Kennedy had predicted he would win the election in the debates, and Nixon had agreed to four. And while Nixon held his own or prevailed on the issues in the four, the first debate may have cost him the election.

Not only did Kennedy come off as personable and self-assured, Nixon looked wan and tired and seemed to echo JFK. . . . Those hearing the debate on radio thought Nixon had won. But on appearances, Kennedy won hands down.

The sad reality we must face is that the egoists and megalomaniacs would not engage in their repugnant acts of self-absorption unless they worked. We have reached another low in our devolving culture when the humble can no longer attain public office. There are exceptions, of course, but they become rarer with each passing election cycle. As a citizenry, we have made a god of government and idols out of the politicians. In the life of the small town, they are our local celebrities. We are smitten with them. The days of a concerned citizen offering himself to the people as a candidate for public service are long gone. Now career politicians wage intense “races” of mass propaganda and self-importance in order to maintain their death grip on their taxpayer-subsidized positions. Narcissism reigns.

And we eat it up.

Leave a Reply