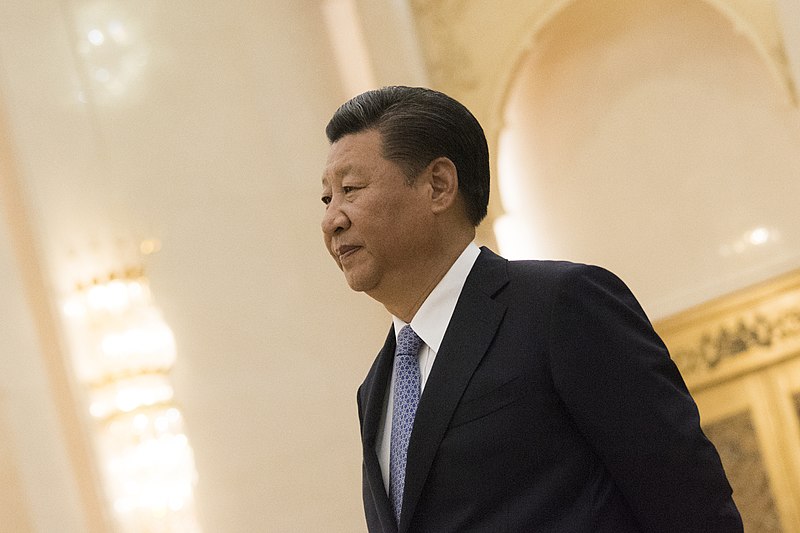

In the aftermath of last week’s finale of the Communist Party of China’s (CCP) 19th congress, many commentators have opined that President Xi Jinping is now the country’s most powerful leader since Deng Xiaoping. This is incorrect. Xi is the most powerful leader since Mao Zedong at home, and arguably the most influential Chinese player on the world scene in history.

After five years at the nation’s helm, Xi has discarded the succession pattern which had been in place for almost three decades since Deng. He has not presented an heir-apparent to the delegates when reelected for his second term—in contradistinction to his two predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, both of whom had accepted Deng’s principles of collective leadership and power rotation. Furthermore, the seven-man Politbureau’s Standing Committee—the supreme decision-making body—has five new members. Three of them are Xi’s close associates and loyalists; one is a former youth leader, and another comes from China’s economic powerhouse, Shanghai. None seem capable of developing an independent power base or acting independently from the Paramount Leader.

The composition of the new Standing Committee is usually a well guarded secret until the end of the Party congress, thus allowing for some last-minute horse-trading. This time the names of its new members were leaked days in advance, which means that Xi was confident that there would be no challenges to his primacy. The only member of the previous Standing Committee to stay on board (except for Xi himself) is Premier Li Keqiang, a weak figure whose position is entirely dependent on Xi’s good will. It is also significant that Xi’s thoughts have been formally included, under his name, in the CCP Charter. He has thus formally surpassed Deng’s contribution to the Charter, which was inserted without naming its author, and achieved formal parity with Mao. This gesture’s practical significance is that anyone opposing Xi will be potentially open to the accusation that he is “an enemy of the Party.”

It is an even bet that Xi intends to stay in power after the expiry of his second five-year term in 2022. His long programatic speech at the opening of the Congress outlined his grand strategy not for years, but for decades to come. Between 2020 and 2035, according to Xi’s vision, China is to develop into a “fully modern economy”; by the middle of the century it should attain great power status and become “a global leader of composite national strength and international influence . . . strong, prosperous, democratic, culturally advanced and harmonious,” capable of shaping events and charting trends. In Xi’s rendering of China’s recent history, there have been three main eras. The first was the liberation struggle and revolution, crowned by victory in 1949, and the PRC’s subsequent consolidation under Mao. The second era was the Reform period under Deng Xiaoping and his (notably unnamed) successors. The current era—which opened with Xi coming to power in 2012—is only starting, and it is supposed to provide the fulfillment of earlier periods. Its unstated leitmotif is clear: putting China first, and making her great again.

It is unsurprising that Xi is not facing significant intra-Party opposition to his grand design. In the traditional Chinese paradigm, an emperor enjoys the Mandate of Heaven if the country is prosperous and stable internally, as well as safe from outside threats. Significantly, the Mandate of Heaven has no time limit: it is contingent upon the performance of the ruler, as evidenced by the tangible fruits of his reign. Those fruits confer the ruler’s legitimacy, and take precedence over any existing institutional arrangement regarding succession.

Xi’s supporters point out that he has exceeded expectations on all key fronts. In 2013 he initiated the new plan for economic reform which should gradually turn China from a low-wage, export-oriented manufacturing economy into a high-wage, technology-driven economy with a highly developed service sector. Gradually but steadily it has been shifting emphasis from investment and foreign demand to domestic consumption. The country’s economic growth is no longer explosive, but under Xi it has been averaging a solid 7% per annum. Over the past three years he has boldly projected China’s hard power in the South China Sea by building and militarizing islands in the disputed areas of “Asia’s Mediterranean.” The simultaneous projection of the country’s soft power is apparent in the audacious Belt and Road Initiative, unveiled also in 2013, which underlines Beijing’s push to take a larger role in global affairs with a China-centered trading network. Geopolitically, it seeks to extend Chinese influence at the expense of the United States and to establish regional leadership in Asia. The time of Deng’s caution (“hide your capacities, bide your time”) is clearly over.

While whetting the appetite of China’s capitalists looking for bold new ventures, Xi has secured the support of the traditionally conservative Party nomenklatura by insisting in his report that there would be no transformation in the direction of an unregulated market economy and that the Party would not give up its monopoly of power. Xi sees no intrinsic contradiction between economic globalization and unrelenting political control. He claims that the present hybrid system is not only successful in China’s case, but that it provides an alternative to the Washington consensus and the blueprint “for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence.” At the same time, an essentially Leninist party will remain in charge of a tightly regulated one-party state. Under Xi, China will not be transformed into a polity more akin to South Korea, Taiwan, or Singapore.

What should be America’s response? For starters, we need to accept that a country’s rising economic strength tends to be reflected in its geopolitical clout. In the late 1880’s the United States overtook Great Britain as the world’s largest economy; a decade later, having defeated Spain, America took over the remnants of her empire. During the same period Germany’s massive economic growth enabled her to establish colonies in Africa and to build an ocean-going navy. Even the tiny Netherlands, having grown rich in the 1600’s, proceeded to establish a commercially-oriented empire in the East Indies, on the Cape, and in the Caribbean.

China’s economy is now equal if not greater in size to that of the United States, and at last week’s CCP congress Xi Jinping made no secret that he will seek geopolitical adjustments to that reality. His current grand strategy is focused on securing supply chains, however, and not on acquiring legal titles to faraway lands or showing the flag for reasons of prestige. The program of building islands in the disputed areas of the South China Sea and militarizing them looks expansionist, but it may be seen as a strategically defensive move to secure the vital node of China’s maritime supply chains in uncertain times—a reflection of the Confucian striving for stability, rather than an audacious bid to establish regional hegemony.

In his inaugural address President Trump said that he would seek friendship and goodwill with the nations of the world, “with the understanding that it is the right of all nations to put their own interests first.” Such realist view of international relations requires balancing the ends and means of his China policy in line with a sober assessment of interests involved. A host of trade and currency issues we have with China are neither ideological nor existential. They can and should be negotiated accordingly.

The essence of America’s dealings with Beijing should be based on Trump’s art of the deal. We insist on rectifying our trade imbalance. If you play along, we are prepared to accept a limited extension of your zone of influence in western Pacific. If you try to turn it into a latter-day Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, we’ll lead a counterbalancing coalition—from Japan and South Korea in the northeast to Vietnam and Malaysia in the southwest—to keep you in check. It is probable that Xi will understand, and opt for a plus-sum-game.

Leave a Reply