When a patient is diagnosed with lung cancer, it is tempting but not useful to harangue him on the evils of his three-pack-a-day habit. But when he refuses to kick that habit, or to accept its link with the disease, or even to acknowledge the seriousness of his condition, it is reasonable to assume that his hold on reality is tenuous, his moral fiber is weak, and his chances of recovery are slim.

President George W. Bush is guilty on all counts. Before we look for a solution to the nightmare in Iraq, it is therefore necessary to recapitulate three key facts.

As we had warned on the eve of the war, the invasion had been planned well before September 11, for reasons different from those proclaimed, and the “War on Terror” was mendaciously used as an expedient context for the premeditated war. Four years later, the exact intentions of different actors (Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Powell, Wolfowitz, Perle, Feith) may be in doubt, but the facts are not.

The improvised and ever-shifting political objective, stated in different ways at different times—to make Iraq democratic, friendly to the United States, staunch in the War on Terror, stable, independent, and unified—had been unattainable ab initio and remains so today.

In geopolitical terms, the main beneficiary of the war is Iran. The United States removed Iran’s archenemy, Saddam Hussein, and replaced him with a Shiite-led government that seeks to remake the whole of Iraq in the image of the Islamic republic across the Shat-al-Arab. The war’s secondary beneficiaries have been Sunni jihadists around the globe, for whom Iraq now provides a focal point, training ground, and mobilizing cause.

At this late stage in the crisis, Americans of various political persuasions should grasp that they share objective interests in Iraq that require nonideological policy responses. Those interests are threefold: to disengage without appearing utterly defeated, to leave behind the least undesirable status quo, and to counter as much as possible the advantage gained by America’s rivals and enemies.

Over the past three months, it has become evident that Mr. Bush is unwilling to accept this reality, let alone to act on it. Analyzed dispassionately and without prejudice derived from the falsehoods and errors of the previous four years, his latest gambit—increasing troop levels by over 20,000 men (forget the “women”) and exerting pressure on the government of prime minister Nuri al-Maliki to get its act together—suffers from two fatal weaknesses.

In military terms, Mr. Bush’s approach confuses tactics and strategy. The tactical novelty of his approach is relatively minor. Instead of going into militia-infested areas of Baghdad, cleaning them up, and leaving—which enables the insurgents to reclaim them within days—increased numbers are supposed to make it possible for U.S. troops to retain a presence in the newly secured neighborhoods. The problem is that those areas would then have to be transferred to Iraqi control, and there is no reliable “Iraqi” force that is a neutral provider of security to all citizens.

The focus on accelerated training of the Iraqis nevertheless remains a regular feature of Mr. Bush’s speeches. A year and a half ago, he declared that “we’re working to build capable and effective Iraqi security forces, so they can take the lead in the fight—and eventually take responsibility for the safety and security of their citizens without major foreign assistance.” He continues to neglect the issue of those security forces’ motivation and loyalty. A Sunni or a Shiite who joins the Iraqi army or police force remains primarily loyal to his sect and to his clan. This fact is confirmed by countless incidents in which armed men in Iraqi police or army uniforms were involved in killing unarmed civilians from the other side of the sectarian divide. The culprits are not guerrillas masquerading as members of the security forces; they are the security forces. The fact that such men are given arms and solid military and police training by top-notch American instructors is counterproductive as long as the use of their skills and their weapons remains unrelated to Mr. Bush’s stated policy objectives.

The depth of the schism between the motivation of Iraqis in uniform and the White House’s goals was embarrassingly visible in the reaction of Kurdish soldiers last January to the order to go to Baghdad and help maintain order. Some deserted their units outright, while others reported sick or went AWOL. All of them complained that the Sunni-Shiite bloodbath in the capital was not their fight, and that they should not be asked to serve outside the confines of their de facto self-governing Kurdistan. Their American instructors warned that the loyalty of the Kurds is to their homeland and its peshmerga militia, not to Iraq, and that mutiny was in the air. If the Kurds, supposedly the most trustworthy allies America has in Iraq, cannot be trusted to conduct operations that transcend the interests of their own group, it is preposterous to expect a “pan-Iraqi” attitude from the protagonists in the ongoing sectarian war, the Shiites and Sunnis, whose mutual disdain claims some 3,000 civilian lives each month.

In political terms, the Shiite tail is already wagging the White House dog. Mr. Bush’s warning that, if the Iraqi government fails to control sectarianism, “it will lose the support of the American people and it will lose the support of the Iraqi people” is hollow. First of all, there is no “Iraqi people” as a coherent polity that shares the sense of common destiny and common aspirations. As for prime minister al-Maliki and his fellow Shiites, their “pledges” are worthless. They do not give a hoot for the “Iraqi people” outside the confines of their own community. They are not concerned about the support of the “American people,” either. If that support (or lack thereof) had been capable of shaping actions and policies on the ground, American forces would be withdrawing from Iraq rather than increasing their numbers. The Shiite leadership, penetrated by Iranian agents and Muqtada al-Sadr’s radicals, will not be intimidated by Mr. Bush’s threat of disengagement, because they do not need him any longer: He has finished the toughest part of the job for them.

As long as we do not have a truly “new” strategy—i.e., one that would be detrimental to the Shiites’ interests—and as long as the ongoing “surge” remains focused on the Sunni insurgency in Baghdad itself and in the Anbar Province, American GIs will continue to pull the Shiites’ chestnuts out of the fire. The Iranians do not mind: They are in the Iraq game for the long term, and they know that, if they play their hand right, they may shoot the moon. As long as an Operation Iranian Freedom is not in the cards (no matter what Neocon Central may wish or hope for), the Americans may remain in Iraq on the Shiites’ sufferance. Of course, there will be no sustained attempt by U.S. forces to go after Muqtada al-Sadr and his militia, because the Shiites in the Iraqi security forces—particularly those in the Ministry of the Interior—would turn against the Americans. Those institutions are thoroughly penetrated either by the Badr Brigades, commanded from Tehran, or by the Mahdi Army, controlled by al-Sadr himself. Had Mr. Bush exerted his pressure on al-Maliki’s predecessors when those Shiite warriors were first detected inside Iraq’s new security services, a purge could have worked.

By now, however, Iraq is in the grip of a vicious civil war, whether Mr. Bush accepts that term or not. By effectively condoning the quasilegal lynching of Saddam Hussein, the administration has taken sides in that war. It may be too late now to follow my recommendation, made shortly before Saddam’s execution, that the United States should try to create a split within the ranks of Iraqi insurgents between the ideologues of jihad, who care little for Iraq as such but simply want to use her as a chapter and a focal point in their global struggle, and those who are driven primarily by nationalist and tribal motives. “This would require overcoming distaste for a dialogue with former Ba’athists and Saddam loyalists, but no such dialogue will be possible if Saddam is hanged under the noses of American soldiers,” I warned last December.

The only way dialogue could begin, at this late stage, would be if the Bush administration grasps that it needs to level the playing field, strengthen the weaker party in the civil war—the Sunni Arabs—and let the Kurds proclaim full independence as a precondition for eventual withdrawal. The least undesirable situation we can leave in Iraq is the one that Tehran and its Shiite clients in Baghdad find least palatable. An anti-Shiite, anti-Iranian, nationalist Sunni-Arab state in central and western Iraq is the best possible bulwark against Ahmadinejad’s intention to create a Tehran-dominated belt that would extend over Iraq and Syria to the Hezbollah-controlled redoubt in southern Lebanon. Furthermore, an independent Kurdistan would inevitably create instability in northwestern Iran, which is the home to between seven and ten million Kurds. (The Turks will scream bloody murder, but their “post-fundamentalist” government also needs to be kept in check, and its regional ambitions in Central Asia and in the Aegean, curtailed.)

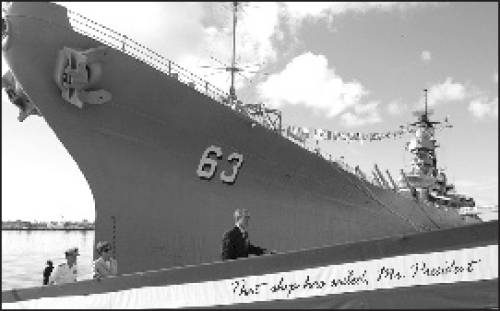

Mr. Bush’s failure to offer a coherent, let alone creative, response to the ongoing disaster in Iraq has no precedent in this country’s history, Vietnam included. Even his rhetoric is devoid of political imagination. Addressing the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis in November 2005, when he unveiled his “National Strategy for Victory in Iraq,” the President declared that we are battling an “enemy without conscience” and that “there will not be a signing ceremony on the deck of a battleship.” Over one year and 1,000 American lives later, on January 11, 2006, he said that we are battling enemies who are “without conscience” and that “there will be no surrender ceremony on the deck of a battleship.”

If Mr. Bush lacks the good sense to find speechwriters capable of coming up with new clichés for such important occasions, it is hardly surprising that his new plans, strategies, or blueprints for Iraq look barely distinguishable from those preceding them. The “deck of the battleship” metaphor displays a doubly patronizing attitude: It assumes that the public will not notice, or mind, that it is being fed recycled platitudes; and—worse still—it imagines that the public needs such metaphors because it does not grasp the intricacies of a challenge as complex as that which he faces.

The challenge is admittedly formidable, but Mr. Bush and his team are the ones who have made it so. It is by now evident that they are unable or unwilling to resolve it. That it will eventually be “resolved” by the likes of Hillary Rodham Clinton or Barack Hussein Obama is neither comforting nor, I fear, avoidable.

Leave a Reply