From the October 1997 issue of Chronicles.

We live in an age when biography flourishes, contrary to earlier expectations. The reason for this is the decline of the novel and the rise of popular interest in all kinds of history, and biography belongs within history. The problem is “all kinds”: for appetite may be fed by a wide variety of junk food. We are now inundated with biographies and autobiographies that are illegitimate, sleazy, twisted, often obscene and fraudulent. Curtis Cate’s Malraux is of a different order. It is an excellent work, this biography of a very interesting man.

Malraux was a writer and a 20th-century condottiere. That makes him interesting enough. The problem is that, unlike in the case of other writers or artists, the man is more impressive than his works. The corpus of his writings is enormous; but his many novels are, at best, ideological period pieces, and I wonder whether his grand books about art will survive beyond coffee-tables where, because of their beauty, they surely belong. Like much of French literature—and philosophy—of the last 50 years, the old French virtue of clarity is not very apparent in them, though there is a fair amount of French wit, not necessarily of the superficial sort. Malraux was an intense man, with an extraordinarily quick (and sometimes incisive) mind. Some of his aphorisms are good, but they give the impression of having been thrown off in the course of a rapid conversation—or, rather, monologue. But then Malraux was a man of action. His life is a series of struggles (and wounds): in Indochinese jungles, in prisons, in Arabia, in Spain, in World War II; struggles with critics and communists, with politicians and women, and—perhaps—with himself.

“Part Peek’s Bad Boy, part Joan of Are” someone wrote in the New Yorker about Malraux—that was silly. In an excellent review of Cate’s book, Simon Leys in the New York Review of Books asks whether Malraux was a phony and answers, yes and no. I agree, though I would say no rather than yes, since a phony is necessarily an opportunist, which Malraux was not. In his introduction, Cate puts it well: “A consummate exhibitionist? No doubt.” But in his letters there is “no trace of epistolary coquetry. . . . They are the letters of a tense, time-rationed intellectual, for whom action, in a noble cause, and an anguished search for human significance in a godless cosmos were far more important than fiction.” The strength of Cate’s book is in his consummate acquaintance with the details and the atmosphere of Parisian intellectual and social life in the 1930’s, and again after 1945 when Malraux became a principal aide to General De Gaulle. (The signs are that his conversion to Gaullism was a result of Malraux’s convictions, unblemished by opportunism.)

He was brave, though I would like to know more of the episode when he sprang up with a toast to Trotsky at a congress in Stalin’s Moscow in 1934. The evidence for that is from his first wife’s memoirs. She was a difficult woman, and not entirely reliable. Malraux’s relationship with women is interesting enough to be essential (I would have liked to read more about his decision to marry his brother’s widow after the war). He was very handsome, which was not only an asset when it came to women: it helped him to stand out in a crowd of unkempt and dowdy intellectuals, together with this ability to speak startlingly, rapidly, and well. He was attractive rather than admirable; impressively interesting rather than interestingly impressive; he pretended that art was the proposition of his life, whereas it was his life that was an artistic proposition. Not an easy subject for a serious biography, yet Curtis Cate has succeeded very well.

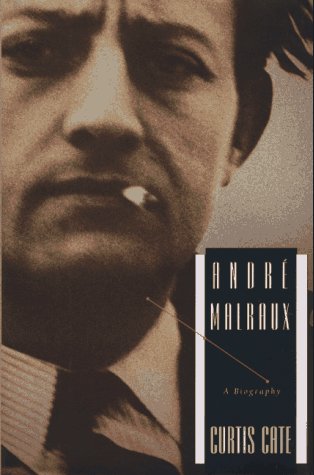

[Andre Malraux: A Biography, by Curtis Cate (New York: Fromm) 451 pp., $29.95]

Leave a Reply