Most writers feel honored by literary prizes—in the way I feel so honored by the award of the T.S. Eliot prize—whether they accept them or not. At the same time, many writers share the wish that their vocation could be carried on anonymously. By the time they have become suitably proficient at their art and have established a proper reputation among their peers and critics, they are no longer compelled by personal glory. They have often tired a little of the notion of fame. A decade or two of essaying the spectacular but exhausting Parnassian slope will do some serious damage to self-pride. This vanity is then fairly annihilated when we raise our eyes to observe how much farther up the ridges our ancestors have established themselves and with what ease they seem to have done so.

The advantages of anonymity are attractive. In the first place, if a critic had no name to point his cruelly barbed shafts at, the guilty writer could escape with a minimum of public embarrassment. He would still writhe and whimper in private, but at least his mother would not have to know the truth; he could choose some other anonymous work, one that had received only praise that rang like silver bells, and claim that one as his own. The other advantage of anonymity is that it would prevent scrutiny of the writer’s personal life.

I do not propose to talk at length about the private lives of authors; they really do not bear much looking into. If writers were as well-known as film stars, and if the tabloids were interested in any dead people besides Elvis, the National Enquirer could fill its pages for years to come with stories of the follies and deviltries of scribblers. I could contribute quite a few myself—except I know that I would receive payment in kind, doubled and redoubled, stories of my own idiocies and misdemeanors that I could not deny. I suppose that writers’ lives are not generally more sordid or dishonorable than those of some of their friends and neighbors, but I have to tell you that I would not care to have mine examined in public. I would feel more embarrassed, and with pretty good reason, than those sexually confused people who appear so compulsively on the television talk shows. Yet finally, I believe that a writer’s private life ought to be made public. I have always tried to share the conviction of my compeers that one’s work is what counts, that one’s private life is irrelevant to his artistic aspirations and accomplishments, but I no longer feel entirely justified in doing so.

Please understand that I am not advocating that writers uncloset great bundles of their dirty linen and begin to soap it up. I am only trying to approach the vexing problem of the writer’s relationship to his community. I believe very strongly that a writer has a duty to belong to his community and to join in actively with its concerns as time and opportunity permit. And if one of the stages toward communal acceptance is the admission and demonstration that writers are only poor miserable sinners like the rest of humanity, then it is a necessary step to take and a small price to pay. Such admission and demonstration may result in public benefit.

After all, many of the virtues that sustain a writer’s work are public virtues as well as private ones. I speak of honesty, steadfastness, perseverance, thoughtfulness, charity, understanding, love of justice and of beauty, patience, intelligence, forgiveness, and good cheer. Any literary work will more clearly approach excellence the more it can encompass these qualities. If the writer expects that these qualities will substantiate and adorn his phrases, why should they not substantiate and adorn his or her life? If the writer knows that criticism will scrutinize the literary work for these qualities and judge it by their presence or absence, why shouldn’t he expect that his life shall be examined and judged in the same way?

Probably it is because the writer also knows that the methods and instruments that are brought to bear upon a literary text or a work of art are inadequate when it comes to judging human lives and personalities. These are unstable, always changing, always influenced by circumstance. The third baseman’s error in the second inning makes him a goat, his home run in the ninth makes him a hero; a besotted melancholic may become a great military leader and then a less-than-great President of the United States.

The work of art, however, is a finished product; it does not change. True, critical judgments of it shall change, and often quite radically, over a period of time, but the work itself in its essential nature shall not change. It is what it is, now and forever, and its critics necessarily stand apart from it. But those who know you and me well enough to judge our lives are so closely involved with us, so directly affected by us, that no objectivity-can be gained; they are biased for us or against us; they contribute to community consensus about us.

What might we gain by putting a writer’s life on trial along with his or her work? “Use each of us as he deserves,” inquires Shakespeare, “and who shall ‘scape whipping?” Well, we know the answer to that question. The writer in particular comes away with deep purple welts. But that is the point, after all. If we can place, for example, the uncanny prescience of Edgar Allan Poe’s fiction alongside his broken and unhappy life, we shall the more readily appreciate what he accomplished. The life we may fairly judge as a dark and melancholy ruin, but against it the fitful lightning strokes of his genius only shine the more electrically. I know I need not rehearse for you the personal failings of Thomas Wolfe or Ernest Hemingway or William Faulkner—or of Tolstoy, Turgenev, Jonathan Swift, Shelley, Byron, Dickens, Ben Jonson, and Samuel Johnson. And I don’t need to remark that their books escape or overcome these failings—and shine the more brightly for doing so.

Let us keep in mind, though, that their books are still part of their personal lives. Writers produce their paragraphs in the privacy of their studies and take from the more secret resources of their personalities the materials that go into the making of their books. And maybe it is there that a certain public balance is struck. Perhaps the courage that his contemporaries sometimes found lacking in Turgenev’s personal life went into the composition of his novel Fathers and Sons. Perhaps much of the bully-boy bluster that was part of Hemingway’s makeup is quietened by the laconic stoicism of his best pages.

Maybe the writer sets down, knowingly or unknowingly, as personal goals what he or she envisions as honorable possibilities of action and thought in a world that generally seems designed purposely to maim and sully honor, to delimit and defeat the highest of human aspirations, and to darken to midnight our most luminous hopes. What can make the writer important in a world that looks like a channel wasteland is the fact that he inhabits this hell along with the rest of us and yet must still be capable of attaining to a vision of a better manner of existence and of articulating this vision. The serious writer soon discovers what his or her duties are in circumstances wide or narrow: to produce the very best work that it is possible to produce and to lead the most upright life that can be led.

But then he soon discovers that both these duties are impossible of fulfillment, and that the second of them, the steadily virtuous private life, is the more impossible. That fact makes it all the more urgent, so he fancies, for him to bring the quality of his work up to the highest standard. If in his or her private life the writer is fated to suffer the ordinary failings of his brother and sister humans, perhaps the production of a more perfect work of art—one with broader and more subtle implications than its rivals promise, with more acute perceptions and a glossier polish—will help to balance out the accounts.

It must be one of the silliest of notions, this idea that one might make up for personal moral deficiencies by means of artistic performance. It is as if someone said, “Well, I can’t seem to make myself stop embezzling money, but my rose garden is the most colorful on the block.” Yet I believe that many artists indulge in this sort of account-juggling. In fact, I think that many of us do, that we often say to ourselves, “I’m aware that I have not been the best mother to my children that I might have been—or the best son to my parents—or the best servitor of my religious principles, but I have always turned in an honest day’s work at the office; I am very good at my job.” This is a common hypocrisy; W.B. Yeats remarked it deftly in a dark little poem called “The Choice”:

The intellect of man is forced to choose

Perfection of the life or of the work,

And if it choose the latter must refuse

A heavenly mansion, raging in the dark.

I don’t quite agree with the great poet’s statement; I think that he puts the case too dogmatically and that the alternatives are not quite so stark as he makes out. An artist who dedicates himself to his work at the expense of his moral life does not necessarily lose his hope of heaven. But when he uses his art as an excuse for his shortcomings he plunges into the mire of hypocrisy—just as the rest of us do when we blame our personal failures on the pressures of our professions. On this point I can speak—sorrowfully—from my own experience.

But the difficulties only begin there. Even if the artist is willing to take a dangerous chance, to throw his most strenuous efforts into art and not into his personal life, further impossibilities await. When I spoke before of the artist’s ability, and duty, to attain to vision in the midst of debilitating daily circumstances, I simplified the case. An artist actually is required to hold in mind two visions; they should be identical, but usually they are only complementary. In practice they may even seem opposed at times.

The artist must possess first and last a vision of moral victory. It need not be a completely detailed vision of a Utopian society or a picture of a perfect individual life, but it must be a vision, explicit or implicit, of how things would be, in the specific set of circumstances that comprise his artistic material, if our better instincts triumphed over our worse. If the artist is a writer, he or she doesn’t have to outline the results of this moral victory anywhere in the pages of the poem or story at hand. But it has to be kept in mind because it supplies the sunshine backdrop that makes the foreground battle of dark shadows—that is, the meat of the story—visible and meaningful. Without a pretty clear notion of the ideal, the depiction of what we accept as real is a waste of time, no matter how accurate and meticulous and convincing the execution.

This fact comprises the artist’s first artistic failure, one that is almost guaranteed. Our images of vice are well defined, dramatic, sharp-edged, and energetic. And why not? We live in vice, all of us; we are handy to its smells and tastes, its appetites and brutalities. Our visions of virtue, however, are pallid and dropsical, puny and naive. When we paint an urban utopia, it turns out looking like a plush hotel lobby; when we draw a rural one, it looks like an expensive golf resort. Twenty-four karat boulevards and a mastery of harp technique: these are our common images for heaven. Dante was able to depict a paradise made up of infinite gradations of light, of the kinds and degrees of virtue that described God’s goodness; these were immediately apprehendable by the senses, the mind, and the soul. Yet it is that poet’s images of hell that most people recall. In fact, most readers of Dante never venture further than his Inferno. If Dante’s paradise has not fixed firmly in the minds of most of us—and it has had 600 years to do so—how shall the contemporary writer successfully portray a vision of the ideal, his faith being so much shakier than Dante’s, his intellect so much less powerful, and his talent dwarfish in comparison?

Only a very few artists have been able to offer a convincing delineation of moral triumph, and I have a doleful feeling that none of them is alive at this hour. This then is the first certain failure the experienced writer knows he must face: the inability to outline with any confidence the figure of the ideal. And without this foundation his work, no matter how expertly fashioned, will fall short of his hopes.

The other failure is imperfect execution. An artist may throw his whole life into the completion of his work, disregarding comfort and safety, careless of future security, reckless of the physical and emotional and financial costs. He may labor at his project almost every minute of his working days and sleepless nights. He may search the planet for materials, hunt the schools and scour the libraries for knowledge. He may build and unbuild and begin again; he will fashion and refashion; he will pray unceasingly. But in the end the finished project comes so far short of his dream of it that it looks like a squalid mud hut situated next to the Parthenon. And then—the worst horror!—the imagined Parthenon fades away like the echo of a watchman’s whistled tune in a midnight warehouse and the actual artwork, the ugly little mud hut, takes its place forever.

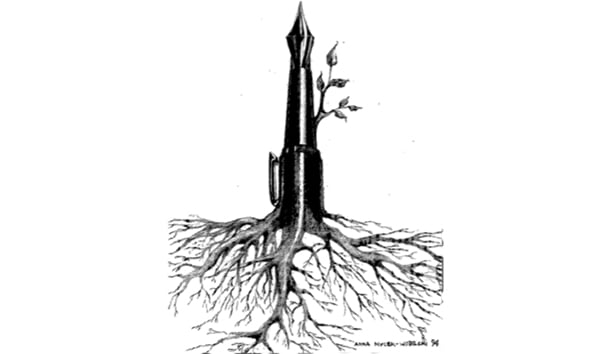

So let the artist’s personal failures be known; let them stand, almost as perverse monuments, as reminders of what he actually desired in the way of an upright life. Works of art remain as monuments in the very same way: they will continue to exist as monuments that only suggest possibilities; they are mere ungainly sad remnants of the dream of grace and beauty that had to lodge at last in a shape not so graceful and not so beautiful. The artist allows them to continue to burden our cluttered world because they point to something beyond themselves; they point toward what might have been. And they suggest what we might have been, and might yet be, if, like the artist, we are willing to unbuild and then build again.

Leave a Reply