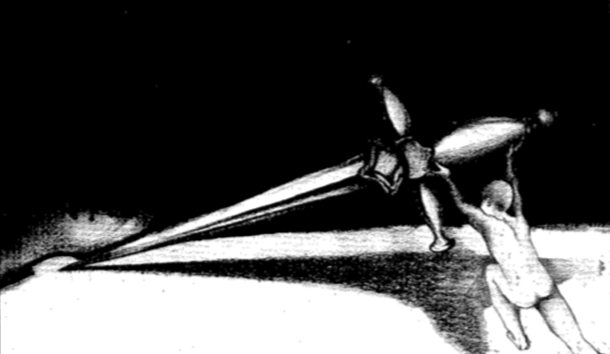

All civilization rests upon the executioner. Despite our feelings of revulsion, “He is the horror and bond of human association. Remove this incomprehensible agent from the world, and at that very moment, order gives way to chaos, thrones topple, and society disappears.” Joseph de Maistre’s insight has alarmed most readers—among them not a few Catholic reactionaries—who have encountered it. There are, it hardly needs to be said, more cheerful terms in which to define civilization, such as the beauty of its arts, the morals of the people, the strength of its institutions, but in practical terms, Maistre’s pronouncement will work as well as any. Without law, without a firm commitment to enforce justice by punishing malefactors, no civilization, indeed no human culture, can be said to exist.

But we can go further than this. In a very real sense we can define the qualities of a culture in terms of its punishments. Some societies—the Japanese and many Amerindian tribes, for example—have exulted in torture as something delightful for its own sake; in others (the Comanche) justice is the rule of the strongest, and a weakling man without friends is powerless against a larger man; in 18th-century England, under the influence of Locke’s theories and the interests of the rising capitalist class, crimes against property were more often capital than crimes against persons.

In the modem United States our criminal justice system is a perfect metaphor for the whole of society. Crimes are regarded, today, not as acts of injustice requiring retribution, but as social problems to be addressed or the symptoms of a disease that needs to be treated. The old concerns—the public’s safety, the satisfaction of justice, recompense to the victim—all are subordinated to the overriding concern of rehabilitation. Ours is a society that increasingly assigns to government the fundamental responsibility for rearing children, treating the sick, and healing the moral and mental ailments that lie at the root of alcoholism, dmg addiction, racial insensitivity, and crime. The state, on this understanding, is a vast therapeutic machine designed to reform the defective character of the people.

Criminals are only the most available class of Americans upon which the state experiments, and the innovations tried upon drug dealers, rapists, and murderers today will eventually be practiced against social drinkers, uxorious husbands, and religious enthusiasts. At the center of all our institutional apparatus are the warehouses and factories of coercion, in which human nature is reforged. The 19th-century poorhouses, the early 20th-century reform schools, and the contemporary gulag of schools, prisons, and treatment centers are all devices created by modern European and American governments to control and re-form the lives and characters of the unruly, the nonconformist, and the insubordinate.

It is no accident that the earliest advocates of prison reform were a coalition of Enlightenment philosophes and nonconformist religious eccentrics. John Howard, the conscience-tortured nonconformist who authored The State of the Prisons, and the materialist utilitarian Jeremy Bentham disagreed on almost everything else under the sun, but on the need to reform the lawless by sticking them in little rooms all by themselves— on this point they were in complete agreement. We have God to thank that philosophers are only rarely kings, since Bentham’s plan for a totally controlled prison, his famous panopticon, was a nightmarish model for the total state.

The term penitentiary is no euphemism, for it was not designed as a house of punishment but as a place where prisoners would be compelled to brood upon their transgressions. Solitary confinement was the key to the early penitentiary; at the English Pentonville, prisoners upon admittance were immediately dispatched to a solitary cell for a period, originally, of 18 months, although as more and more prisoners went insane, this was reduced to nine months. Once out of solitary, the prisoners were still deprived of human contact: they worked alone at their tasks and had to wear hooded masks whenever they assembled—to prevent the formation of any social relationships. The rule was simple: no communication of any kind was tolerated.

Such coldly inhuman treatment aroused the ire of radicals and reactionaries alike. Even the Utopian liberal, William Godwin, realized that human character, which, is formed by society, could only be degraded under such conditions. Every generation since Godwin has called for prison reform. Tocqueville’s visit to America was occasioned in part by his desire to study the new-model prisons, and he records the observation that criminals came out of these prisons more hardened and vicious than they went in. After two centuries of reform efforts, the same complaints are being made. Prisons are inhumane and overcrowded graduate schools in felony, which degrade the inmates without deterring crime.

Things are, of course, worse in our own day. By the end of the century, the inmate population (including prisoners on furlough, parole, etc.) of the United States will surpass four million, and the annual cost for the corrections apparatus will reach $40 billion. They could all be sent to a state university for that figure. No one is happy with the system. Liberals complain that it is brutal and inhumane—and they are right—while conservatives insist that liberal remedies, such as furloughs and work-release, are turning vicious criminals loose upon the public—and they are also right.

We all know the system doesn’t work, but the only alternatives are, on the one hand, more prisons and longer sentences, or on the other, more coddling of murderers, armed robbers, and rapists. The public debate over the Jeffrey Dahmer case in Milwaukee is a perfect illustration. One side insists Dahmer knew what he was doing and ought to be put away for life; the other declares he is insane and ought to be put in an asylum for at least a year until he straightens out.

But aren’t most criminals at least a little bit crazy? A stockbroker, who can honestly cam a hundred thousand (or many times that) a year must be unbalanced to jeopardize his career by engaging in insider trading, and the same argument could be applied to virtually everyone except dmg dealers, whose cost-benefit calculation strikes me as entirely rational: let’s see, four bucks an hour at McDonald’s or fifty grand for a few days’ work. Even at the risk of a few years on the inside, it is an easy decision.

Of course a homosexual cannibal who designs a temple of death is crazy, crazier than a mad dog that we would unhesitatingly put to sleep. Execution is the mildest punishment Mr. Dahmer deserves, and anything less is an outrage against our sense of justice. But Wisconsin gave up the death penalty, and the best the citizens of that state can hope for is a verdict that will give them the privilege of supporting Mr. Dahmer for the rest of his life. I say, tum him loose with a ten-second head start in front of his victims’ relatives.

The usual conservative remedy for the problem of crime is more police, but what good can the police do in Milwaukee, where they are ordered to protect the life of Mr. Dahmer? In most cities now, the primary function of the police is that of protecting violent felons from the just revenge of their victims and their kindred. The vast police network of the United States only exists, it sometimes seems, to check drivers’ licenses or arrest good parents who love their kids enough to spank them. I am not blaming the police officers themselves; they are only carrying out laws made by judges and legislators, in that order. What we don’t need is more police but more executions.

The sterility of most “thinking about crime” is revealed by the hostile refusal to consider any but the narrowest range of options. In the exclusive concentration on the merits and defects of the present system, the whole point of the system has been lost sight of. There are a number of different ways of breaking down and classifying the objectives of criminal justice, but the primary categories would seem to be: retribution, compensation, protection, and humanity. None of these is secured under the current regime. Five to ten years of imprisonment for murder or three years for rape is simply not satisfactory as retribution. It is possible to work out a loftier scheme than the lex talionis according to which the man who accidentally puts out another’s eye must lose his own, but it is not for nothing that we imagine justice to be weighed out on a balance. The severity of the crime must be matched by the severity of the punishment; otherwise the victim and his family can never be satisfied.

Victim compensation was all the rage in the 1980’s, but very little was actually done to compensate either victims or their families for the wrongs that had been done. No compensation has been proposed for the investors who lost out because of insider trading, for the old ladies who paid a band of gypsies to resurface their driveways or repair their roofs, for the parents whose children were murdered in school because the principals and superintendents refuse to protect the students from violence, or for the women whose lives have been turned into an unending nightmare by a generous parole board collaborating with an AlDS-infected rapist who had a string of previous convictions.

The truth is that we are not free to walk our own streets in safety; large numbers of students now carry guns and knives to school; rape has become so prevalent that it is treated as a minor crime, the subject of jokes and televised trials. However, the same book out of which we read the rights to rapists and murderers gets thrown in the face of anyone who challenges the regime either by protesting taxes or making an insensitive remark.

Last and least, a criminal justice system for a civilized people should be humane, that is, it should not violate the integrity of our human nature. Human beings are, in principle, autonomous souls with an inherent right to make their own decisions and to abide by the consequences. Any attempt to reform them against their will is inherently evil, because it denies the “personhood” of the offender. The whole underlying notion of rehabilitation is not merely bogus—few people, after all, can actually be reformed by an institution—it is profoundly evil. If I have robbed or injured someone, then let me pay a just penalty; that is society’s right. What no one has a right to do is to fiddle with my conscience, by sleep-teaching, hypnosis, drugs, therapy sessions, or solitary confinement. If my character is so bad that it must be altered by force, then kill me and be done with it, but do not try to rob me of my soul. If ever there were a punishment that could be described as cruel and unusual, it would be long-term imprisonment combined with the ministrations of counselors.

Since none of these objectives is being met by the current system of imprisonment and parole, it is time to think of alternatives. We do not have to reflect very long to recall that throughout human history, societies have had recourse to a variety of punishments and only rarely experimented with prisons, except as holding tanks for criminals awaiting trial or sentencing and convicts awaiting execution. These methods ranged from the pillory to the gallows and could easily be reinstituted in a system designed to meet the peculiar needs of postcivilized man.

Shame is the ideal method of punishment for lawbreakers who still have a conscience or a sense of face. For juvenile offenders, nothing could be more effective than to subject them to the pillory in their own school yard or expose them to ridicule on closed-circuit television shown to their gym class. The same techniques could be applied to older but nonviolent criminals who value their reputation. Peculating congressmen, teachers, and clergymen who violate the trust we put in them, and all such pillars of the community, could be degraded in various ways on a special segment of the evening news. They might also be compelled to wear some badge of shame, wherever they went, to warn strangers against their wiles.

For many of us, however, the pillory needs to be accompanied by a more forcible reminder, and it used to take months to heal a set of stripes inflicted by a good flogger. More than fifty or sixty lashes is probably excessive, although the English used to lay them on by the hundreds. For white-collar criminals, the harshest punishment would be the payment of confiscatory fines levied upon their incomes for a period of years. (Defaulters would face sterner measures.) The few million paid by Mr. Boesky are not enough, and the money should not have gone to the government but to his victims.

Some thought should also be given to compensating victims of theft and violence. If someone invades my home and steals the television, it is not enough just to get the set back. The burglar must be made to pay me for the inconvenience and the fright. A few thousand dollars, enough for a week in Paris, might make me feel so good that I would look back with pleasure on the event. Criminals guilty of capital crimes might be made to sell off their organs to a hospital and give the money to their victims’ families. It sounds grisly, but not nearly so grisly as rape and murder.

Next in order of severity among traditional penalties is mutilation, the loss of a limb. A career pickpocket, if deprived of a finger or two, might consider another profession, and if he did not he might find himself with no hands at all. If we shrink from applying the death penalty to a first-time rapist, then there is an obvious piece of surgery that could be performed.

Many political crimes could best be treated by banishment, and it would be small loss never to see the faces of Alan Cranston or Tony Coelho in these United States, but for many serious crimes the only just and fitting punishment is death. These are all, it goes without saying, crimes against persons and all involve death or the threat of death. As a bare minimum, murder, rape, armed robbery, kidnapping, and arson should all be capital crimes, because in each case the criminal has either killed or threatened to kill his innocent victims. For everything but murder, we might well wish to consider mitigation for many (although not all) first-time offenders, but a man who makes a habit of sticking a pistol up a 7-Eleven clerk’s nose will soon!er or later pull the trigger.

My father always told me never to point a gun at anyone j and never to threaten anyone! unless L meant to carry through the threat, because—he said—the minute you point a gun at someone, he can only assume you are willing to kill him. Under those circumstances, he has the right to kill you first. The same reasoning applies to armed robbers, muggers, and rapists, who make us slaves to terror by telling us, “Do what I want or 111 kill you.”

A liberal use of the death penalty for violent crimes ought to be the least controversial of my suggestions. I don’t know how many would-be murderers and muggers would be deterred by the knowledge that the careers of five or ten thousand of their colleagues had been interrupted by a rope (gas chambers and electric chairs are too expensive, and their technology smacks of a bad conscience), but at least that five or ten thousand would no longer be practicing their profession. That much is certain. But no society can make a claim to the most rudimentary sense of justice, if it fails to kill the killers as a matter of routine.

Of course, there may be mistakes, and an occasional innocent man will be executed, although it is remarkable how many wrongly convicted criminals are thugs who got fingered for the wrong job. Mutilation, it will be said, is barbaric, but how many men would not give up a hand or even an arm in preference to spending seven years in a state prison as the wife of Mike Tyson?

What do we do in the long interim between the present injustice and the eventual restoration of sanity, which will only take place after the entire collapse of what we continue to call “civilization”? If each generation of revolution and reform in penology has alienated us farther and farther from the fundamental principles of justice, can we go back, if only in our own minds, to the basics?

The foundations of criminal justice are to be found not in the sovereignty of the state but in the rights and duties of individuals and families that must protect themselves against aggressors and take revenge for injuries received. The Greeks never entirely gave up the notion that murder was, after all, an affair between families, and they invoked the city’s judicial apparatus only as an efficient and peaceful vehicle for handling the negotiations. The Romans, who made more of a science of their law, went further in transferring authority to the state, but they never repudiated the right of each man to repel force with force.

The Germanic conquerors of Europe brought with them more personal and familial legal notions that would not have seemed entirely strange to Romans of the early Republic. Anglo-Saxon law was slow to abandon the idea that the main object of criminal justice was the placation of the victim. Our ancestors were for the most part rough men who were all too willing to exact bloody revenge from those who had offended them, and the Franks, Lombards, and Northmen of the continent, as well as the Anglo-Saxons, Picts, and Scots of Britain, were happy to kill their enemy or wipe out his family, if their claims were not satisfied. In more traditional parts of the United States (the West and the South) dueling did not fall entirely out of fashion until near the end of the last century, and committees of vigilance have been keeping the peace since before the Revolution.

Law and order are usually better than order without law, but what are we to do when we have law without order? Obedience is a great political virtue, and I have more than once described the more aggravated forms of civil disobedience as tantamount to treason. However, the duty of self-defense—and revenge—precedes the state, and if we have delegated this responsibility, we have not abrogated it. As John C. Calhoun observed of states’ rights, “to delegate is not to part with or to impair power.

The classic text on Christian obedience in Romans chapter 13 says:

Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers. For there is no power but of God. . . . Whosoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God: and they that resist shall receive to themselves damnation. For rulers are not a terror to good works, but to the evil. Wilt thou then not be afraid of the power? Do that which is good, and thou shalt have praise of the same. For he is the minister of God to thee for good. But if thou do that which is evil, be afraid; for he beareth not the sword.in vain.

But what if the state does hold the sword in vain? What if government wields the sword only to protect physicians who grow rich by killing unborn babies, pornographers who prostitute children, and the army of vandals that is now waging a reign of terror in American cities. Ordinary Americans are beginning to understand that if they want to protect their homes or keep their neighborhoods safe, the police cannot help them, and the law won’t. And if, after all the precautions in the world, one of the savages should break in and—God forbid—murder a man’s wife and children, he may have to pick up, for a time, the sword the state has cast aside.

Leave a Reply