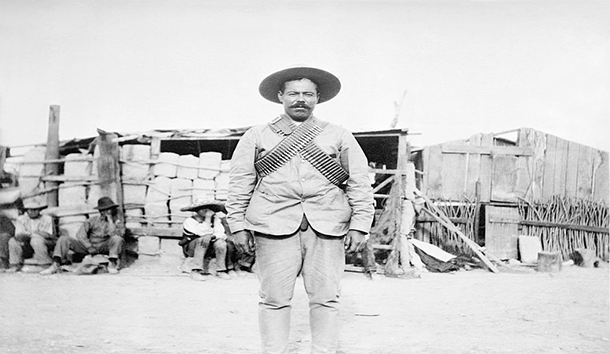

There are hundreds of Mexican restaurants in the United States named for the revolutionary Pancho Villa. Photos of the Durango native line the walls, and his raid on the small American hamlet of Columbus, New Mexico, is celebrated. Nowhere is mentioned the many atrocities Villa and his forces regularly committed. Torture, rape, and murder were not uncommon. Yet, in today’s educational climate it is doubtful that more than a handful of professors describe him or his raid in anything but p.c. terms. As with his true name, Doroteo Arango, his true history will continue to be obscured.

Many theories have been proffered to explain Villa’s motivation for attacking Columbus: President Wilson announced U.S. support for the Carranza government; the United States allowed Mexican troops railroad passage from El Paso to Douglas, Arizona, where they recrossed the border and defeated Villa in the battle of Agua Prieta; a Columbus merchant cheated Villa on an arms deal. There may be some truth in each of these theories, but a far more likely explanation is something we know for certain. Having endured a rugged winter after being badly defeated at Agua Prieta in November 1915, Villa found his arms, ammunition, horses, mules, and supplies nearly exhausted. His scouts told him that Columbus, only three miles above the border, and the adjacent U.S. Army post, Camp Furlong—not much more than a few buildings, a collection of tents, stacked supplies, and corrals—had everything they needed and would be soft targets.

An hour past midnight on March 9, 1916, Villa and 500 of his mounted marauders passed through a gap his scouts had cut in the barbed-wire border fence south of Columbus. A mile short of town, Villa deployed his Villistas, some dismounting and going forward on foot. They waited in the darkness for the word to attack. At 4:10 a.m. came the cry, “Vayanse adelante, muchachos! Muerte a los gringos!”

Pvt. Fred Griffin, standing guard at Camp Furlong, challenged the shadowy figures he saw approaching. Gunfire erupted in reply. He was hit by several rounds but killed three of the attackers before he collapsed, mortally wounded. The gunfire awakened the camp and the town. Residents peered out of windows to see hundreds of Villistas shooting into and torching homes and businesses. Railroad worker Milton James tried to lead his pregnant wife from their flimsy clapboard dwelling to the relative safety of the adobe-walled Hoover Hotel. A Villista shot her in the stomach, killing both her and her baby. Nine others were gunned down, and two more wounded. Dozens of armed civilians began to return fire, often with deadly effect.

The troopers of the 13th Cavalry at Camp Furlong, most of them sound asleep when the first gunshots rang out, sprang into action with surprising alacrity. Lt. James Castleman, commanding officer of Troop F, raced to organize his men for a counterattack. A Villista fired at him, missing by inches. Castleman returned fire, and the Mexican fell to the ground, dead. The lieutenant found his men already armed and formed up by Sgt. Michael Fody. Castleman led them in an attack on the Villistas’ right flank, turning it and driving the Villistas from the regimental headquarters. He then moved his men into Columbus and began driving Villistas from businesses and homes.

Lt. John Lucas, who would serve as a major general with George Patton during World War II, raced barefoot from his quarters to organize his machine-gun troop. Within minutes he had his men firing the notoriously unreliable French-made Benet-Mercie guns. They worked well enough to turn the Villistas’ left flank and allow Lucas to move on the business district. Soon the forces of Lucas and Castleman had the Villistas in a crossfire, and the Mexicans could do nothing but flee for their lives.

About this time Col. Herbert Slocum, commander of Camp Furlong, arrived from Deming, some 35 miles to the north, where he had spent the night following a polo match. He immediately took command and had Maj. Frank Tompkins lead a force of 55 troopers in hot pursuit of the fleeing Villistas. Tompkins followed them across the border and 15 miles into Mexico, killing more of the raiders along the way. In their haste to escape, the Villistas dropped most of the supplies and arms they had looted, and abandoned many of the horses they had stolen. Tompkins would be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Eight men of the 13th Cavalry had been killed and another six wounded. The bodies of 67 Villistas lay in Columbus and Camp Furlong, and several dozen more along the route of retreat. Blood trails indicated dozens more had been badly wounded but carried away. The Army estimated that Villa lost nearly 200 of his men. Villa himself had watched the battle from the safety of a hilltop west of town.

Although the Punitive Expedition later sent into Mexico failed to capture Villa, it hardly mattered. After his defeats at Agua Prieta and Columbus, he was a greatly diminished figure whose power was restricted to a portion of western Chihuahua. When revolutionary activity finally ceased in 1920, he was granted a hacienda near Parral. He did not live long to enjoy it. He was assassinated in 1923.

Leave a Reply