In a small, dimly lit room at the Burmese immigration office, on the border of northern Thailand and Burma, there is a large, luminous portrait of Gen. Than Shwe, festooned with medals and ribbons.

His steely gaze surveys the hundreds of foreign tourists who cross the Thai-Burma border bridge to visit the ramshackle, open-air market at Tachilek each day. He is also the embodiment of strict and relentless censorship, from poetry to the latest Rambo film (set in Burma)—everything controlled by his Orwellian regime.

However, less than 50 meters away, under the bridge on the Burmese side—and for a little over a dollar—you can buy films depicting the sexual abuse and torture of British, American, European, and Asian children. Some are aged as young as four, while none is older than twelve.

And unless you are a saffron-robed monk, you will not be searched on the way back across the border into Thailand.

While the market at Tachilek is notorious for fake designer goods, dubious precious gemstones, the teeth, skulls, and skins of endangered animals, and phony, placebo-inducing pharmaceuticals, the child pornography is real.

The chilling tears and shrieks are not the result of dubbing or digital manipulation.

The graphic footage of a five-year-old Cambodian girl having her arms strapped to her legs with electrical tape before being subjected to unspeakable violations is unrehearsed.

The diminutive seven-year-old British girl who is raped by a 200-pound, black-hooded man while another man films has been deceived by someone she trusts.

The Indian girl, aged about six, wearing only school socks and shoes, has not been groomed to look like a primary-school student: She is a primary-school student. And she is violently raped.

Unlike the ubiquitous image of Sad-dam Hussein on playing cards and cigarette lighters, peddled by the hundreds of panhandlers who whisper conspiratorially to tourists about sex with children, no two girls or scenes of abuse in dozens of different films and hours of footage are the same. And while the fake designer goods are mass produced for a large, diverse market, the record of abuse of these young girls is sold exclusively to a dedicated, hard-core group of connoisseurs by the world’s most malevolent cottage industry.

The Tachilek market and the bridge crossing at Mai Sai, where naked children swim in the muddy waters below, are well known to international human-rights groups, NGOs, and law-enforcement bodies as strategically important to regional human trafficking and narcotics smuggling.

On the Burmese mountains and in the dark ravines, there are dozens of makeshift camps where ethnic minorities, uprooted, persecuted, and displaced by Burma’s military regime, seek refuge. Many of them make their way to Thailand to find work.

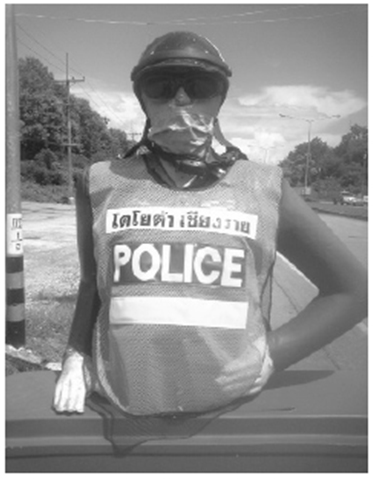

On the Thai side, in the lowlands of rice and corn fields, are hundreds of crumbling orphanages where thousands of children are sent to become another name on a large rickety chalkboard that, as one aid worker said, does not reflect the real number of transient children in care. And while Thailand has set up roadside checkpoints on the highway between Chiang Rai and Mai Sai, in reality they consist of life-sized, fiberglass figures of Thai police officers in their regulation white motorcycle helmet, sunglasses, and brown uniform, signaling to drivers to stop.

Sadly, unlike the fake designer goods at the Tachilek market, the Thai police dummies lack verisimilitude.

Burma is a party to the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child (1990) but has not yet signed the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography (2000). States that are parties to the convention and optional protocol are, in addition to protecting children from all forms of abuse and exploitation, obliged to take appropriate measures to thwart the production and distribution of child pornography.

Burma’s own child laws state that it is a punishable offense to use children in the making of pornographic material, while its penal code makes it illegal to exhibit or distribute any obscene material. The penalties range from fines to terms of imprisonment of up to two years. However, with Burma’s state infrastructure and law-enforcement bodies riddled with corruption, it’s no surprise the Tachilek market is honeycombed with illegal goods.

Behind legitimate shop fronts are secret doors and false walls leading to hidden inner rooms where thousands of films depicting the most depraved, unspeakable social taboos are displayed and sold.

The abhorrent trade in child pornography flourishes while the omniscient Burmese regime scrutinizes the plots of the latest Hollywood films for conspiracies and subversion against the state—when the greatest subterfuge is within.

There are no borders or checkpoints en route to the heart of darkness.

Leave a Reply