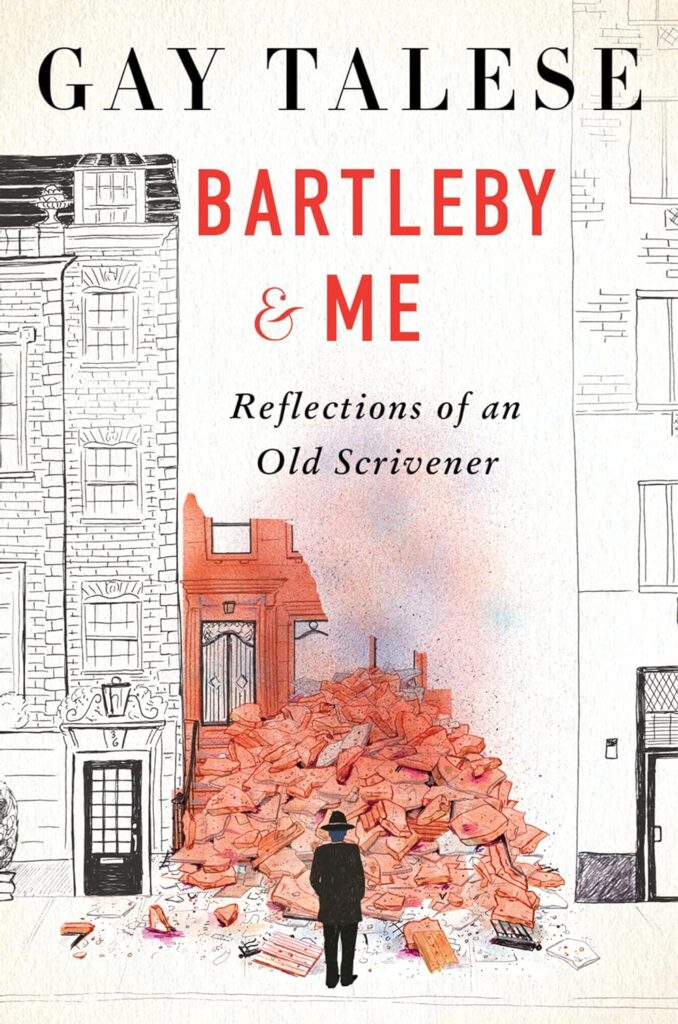

Bartleby & Me: Reflections of an Old Scrivener, by Gay Talese (Mariner Books; 320 pp., $28.99). Substack started as a shrewd concept but it didn’t take long to transmogrify into journalism’s Cloaca Maxima. Each time Substack plops its weekly algorithmic chamber pot of “posts assembled just for you” into my inbox, I want to disinfect my email. I now only read authors who don’t hawk their wares on Substack. Among those are Gay Talese, whom Tom Wolfe called the inventor of “The New Journalism.”

Cancel six of your $5/month Substack subscriptions and use that $30 to buy the percipient Talese’s capstone book, Bartelby & Me. In his first sentence, Talese observes that “New York is a city of things unnoticed” (particularly by brainless Substack readers glued to their phones). The book covers Talese’s reminiscences about his remarkable journalism career, which was built on noticing things others didn’t.

Talese’s career highlights include his Ahabesque pursuit of Ol’ Blue Eyes while researching his famous April 1966 Esquire article “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold.” They also include the convoluted history of a brownstone in his neighborhood that an angry divorcee blew up to spite his ex-wife. As proof of the axiomatic truth of Talese’s first sentence about “things unnoticed,” I heard that explosion myself but never noticed the complexity behind it. And that’s even before Substack tried to destroy my reading regimen.

Talese notices the unnoticed with authorial aplomb. As a result, the rest of us can make better sense of today’s societal madness. He noticed that mid-century newspaper reporters used to serve as “fact-gatherers” while editors worked in healthy opposition as “fact-checkers” in order to “better serve … the interests of the paper.” To the extent that real reporters and editors still exist, they collude to push their political agenda, the paper’s interest be damned. He also noticed the best obituary writers used to conduct face-to-face interviews with people who knew the deceased to craft the best tributes. That was before “working from home” made such due diligence uncommon.

Talese also notices other noticers, especially of things otherwise unmentionable. In a June 1963 interview at New York’s Pierre Hotel, Alabama governor George Wallace noticed Manhattan was “the citadel of hypocrisy” since “hardly any Black people, even those who could afford it” could buy Fifth Avenue apartments due to tacit discrimination. But that duplicity never stopped any Pecksniffian Gothamites from “ranting about equal rights” in the South. Touché.

I was so rapt in Talese’s prose I didn’t notice my latest email from Substack.

(Mark G. Brennan)

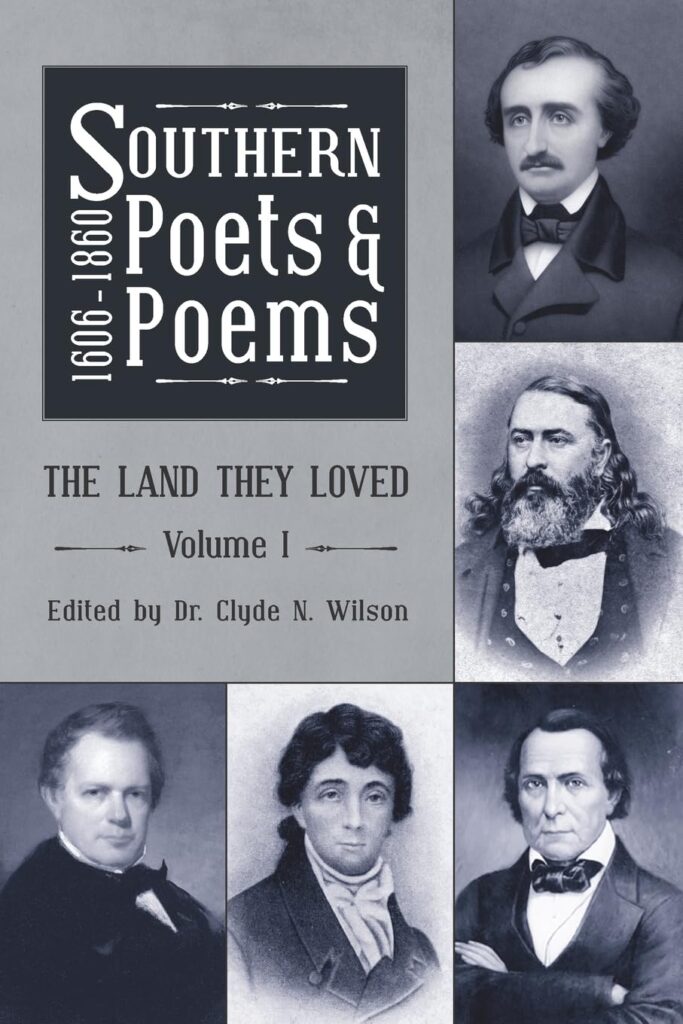

Southern Poets and Poems, 1606 -1860: The Land They Loved, by Clyde N. Wilson (Shotwell Publishing; 186 pp., $19.95). That Southern belles-lettres stand honorably beside the literary achievements of New England is borne out by this anthology, the first in a projected series of five. The editor, the eminent Clyde Wilson, is emeritus professor of history at the University of South Carolina. For his guiding principle in assembling this first volume, Wilson cites the Southern poet William Gilmore Simms: “The emotional history of a people is as necessary to the philosophical historian as the mere details of events in the progress of a nation.”

To that end, Wilson has selected a wide range of works connected to the South in general or to individual states from Virginia to Texas. Many are historical gems; some are very good poetry. Where contemporaneous verse is lacking, a few key prose passages memorialize great figures, such as Washington, Jefferson, and W. B. Travis of the Alamo. Wilson begins with “Ode to the Virginian Voyage” (1606), by Michael Drayton, an English Renaissance poet, who never visited America but wished to honor Raleigh’s enterprise. There follows a poem on Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia (1676), considered by the critic and editor Louis Untermeyer as the best poem written in America in the 17th century, and America’s “first indubitable poem.”

The lives of the South’s racial minorities are depicted in poems such as “Negro Song” by William Alexander Caruthers, in a poem on an Indian bride by Edward Coote Pinkney, and in two “Choctaw Melodies” in rhymed couplets by Alexander Beaufort Meel.

Among women authors is Louisa McCord, whose fine blank verse in her 1851 play, Caius Gracchus, still reads well.

Biographical sketches of the poets precede the selections. Familiar figures include William Byrd II, Dolley Payne Madison, Francis Scott Key, Edgar Allan Poe, Mirabeau B. Lamar, Stephen Foster, and Henry Timms. Also William Walker, who published the 1835 hymn book Southern Harmony and chose the tune for “Amazing Grace.” The anonymous 1781 author of “The Battle of King’s Mountain” is featured among poems celebrating Southern heroism. Though no period verse on the Alamo seems to survive, it has its own short section, containing the original memorial inscription and a 20th-century poem by Stark Young.

(Catharine S. Brosman)

Leave a Reply