Travel writing in the post-World War II era gradually became the prosaic stuff of Sunday newspaper supplements, nothing more than Baedeker-type guides to fancy hotels and chic restaurants in foreign capitals. Bruce Chatwin revived the classic traveling-by-the-seat-of-your-pants school, a genre historically practiced by worldly wandering Brits as disparate as Lord Byron, Richard Burton, and Graham Greene. The idea is that a travel book cannot be interesting unless the journey’s destination is remote and desolate, and the going is hard, even dangerous.

“Horreur du domicile,” said Baudelaire, and Chatwin took it to heart. After a stifling period in his early 20’s working as an up-and-coming “numbering porter” at Sotheby’s auction house in London (where he honed his prose style writing short catalogue entries of art objects), Chatwin’s doctor warned him that his job was inaugurating a nervous breakdown and deterioration of eyesight and advised him to seek out “far horizons.”

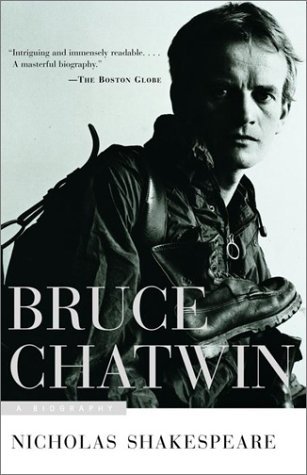

We have the dusty-booted, mud-caked details thanks to Nicholas Shakespeare’s Bruce Chatwin: A Biography. At 618 pages, this well-written book is the probable last word on a writer who—despite authoring only a half-dozen books and dying of AIDS at 48—continues to cast a long shadow over all serious travel scribes. Today, glossy magazines such as Outside and Sports Afield feature articles by Chatwinesque wannabes swathed in Gore-Tex and chattering on cell phones in equatorial jungles or among Himalayan peaks. This high-tech version of Chatwin’s rucksack method has become an advertising tableau in the pages of such magazines: Thanks to Bruce Chatwin, Patagonia may soon own Patagonia.

Chatwin was born in Sheffield, England, in 1940, the eldest of two sons of Charles Chatwin—a lawyer and war-time naval officer—and his wife, Margharita. True to his class, young Bruce was sent to boarding school at Old Hall in Shropshire, and then to Marlborough College. By his own admission, he was a poor student (“I was hopeless at school, a real idiot, bottom of every class”) though an omnivorously well-read polymath who dabbled in literature, art, and archaeology. A school friend once described him as “a 19th-century dilettante”—one, that is, in the best sense of the word.

Chatwin’s modus operandi in traveling was simple: Bring to an exotic locale erudition, an insatiable curiosity, and a sharp eye for the bizarre. Court hunger, illness, and exposure to the extremes of weather, as well as unpleasant adventures with local bureaucrats and cops resulting in short stints in jail or the paying of bribes. Like great travel writers before him, Chatwin seems to have been neurotically driven to escape himself and “the perversion of home.” He was a lifelong bisexual who nevertheless enjoyed a 24-year, mostly happy marriage to the American Elizabeth Chanler (a union that withstood his sexual peccadilloes), and whose remote travels encouraged what has been called “sexual tourism.”

Aimless wandering in Europe, Africa, and Central Asia in the late 60’s and early 70’s resulted in frustrated attempts at writing, producing only some forgettable magazine journalism and a turgid anthropological treatise titled “The Nomadic Alternative.” Despite Chatwin’s Herculean efforts, the latter never saw publication, though elements of it appeared in The Songlines (1987). From 1972 to 1975, Chatwin was a feature writer (specializing in travel) for the Sunday Times of London, where he came under the editorial wing of Francis Wyndham, a legend in British journalism. Chatwin ranged far, and in his reportorial wanderings interviewed Indira Gandhi and Andre Malraux (among others), all the while reinventing the travel genre. Remembering Hemingway’s advice to a young writer to ditch journalism as soon as one can, Chatwin took a sabbatical in 1974, leaving Wyndham a terse note reading: “Gone to Patagonia.”

It was Chatwin’s long-held ambition to visit the sparsely populated, 800,000 square-mile amorphous region in the southern reaches of Argentina and Chile, ending at Tierra Del Fuego: the “Land’s End” of the Americas. The fruit of his four-month sojourn was In Patagonia (1977), a potpourri of history, archaeology, anthropology, and paleontology, seasoned with his usual dollop of chaotic travel method. The book was an international bestseller and won its author numerous awards, including Britain’s 1978 Hawthornden Prize. To this day, it inspires legions of less talented writers and ordinary trekkers clutching their dogeared paperback copies, reinforcing the idea that the best way to cheapen a pristine place with commercialization is to write well of it.

Chatwin’s late 70’s trips to Brazil and West Africa resulted in the short novel The Viceroy of Ouidah (1980), an historical fiction whose main character is the real life Francisco Felix De Souza, a rags-to-riches-and-back-to-rags figure involved in the 19th-century transatlantic slave trade. This dark novella has been compared to the works of Conrad.

In 1987, Chatwin published The Song Lines, finally putting to good use his theory of nomads: that is, how certain tribes living in some of the world’s most inhospitable places managed to endure, and even to thrive, for centuries as empires and nation-states crumbled around them. According to Nicholas Shakespeare, the aborigines of the Australian outback were for Chatwin “a structure on which to hang not only his nomad theories, but more or less everything else in his notebooks . . . whether [noted] in an Afghan bazaar, a Sudanese desert or a New York drawing room.” The 80’s also saw the publication of On the Black Hill and Utz, two novels that garnered critical acclaim.

At the same time, the author’s growing fame encouraged his worst excesses. Sexual tourism resulted in an HIV-positive diagnosis in Zurich in 1986. Chatwin refused to accept it; until his death three years later, he steadfastly insisted that he was suffering a chronic infection caused by the bite of a “Chinese bat.” During those years, Chatwin struggled to put together a collection of miscellaneous pieces called What Am I Doing Here (published posthumously), before dying in Nice surrounded by his wife and a few close friends.

[Bruce Chatwin: A Biography, by Nicholas Shakespeare (New York: Doubleday) 618 pp., $35.00]

Leave a Reply