A wash in reviews of Cornwell’s portrait of Pius XII, I felt surfeited by the book even before it arrived in the mail. To call this biography unflattering is meiosis. John Lukacs is right to say that, while Cornwell’s production is being featured by the History Book of the Month Club, history itself is what Cornwell mercilessly clubs in his assault on Eugenio Pacelli, the papal nuncio to Germany who became Pope Pius XII.

Cornwell’s intemperate attacks do not seem justified by the evidence cited. If Pius, as a well-wisher of Nazi tyranny and an antisemite who typified the Church’s “habitual fear and distrust of Jews,” really was “Hitler’s Pope,” Cornwell does not make these charges stick. It is one thing to claim that Pius did not go far enough in criticizing Nazism, when in his Christmas 1942 address he referred to the “hundreds of thousands [not identified specifically as Jews] who without any fault of their own, sometimes only by reason of their nationality or race, are marked down for death or gradual extinction.” But these diplomatic tropes do not establish Pius’s enthusiasm for the holocaust, anymore than his failure to take strong action when the Nazis entered Rome in October 1945 and imprisoned its Jews. What exactly should Pius have done at that time? Denunciations of Nazi antisemitism by Catholic bishops in Holland three years earlier had resulted in the extermination of Dutch Christians of Jewish descent, including a future saint, Edith Stein. What leverage (or military divisions) did the Pope have to induce the Nazis to become gentle and caring people?

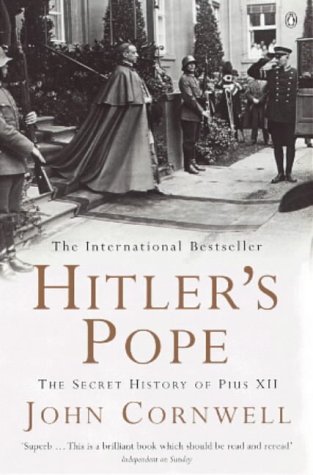

It may be appropriate to ask, as one reviewer in Osservatore Romano has, how Pius —who had been viewed by Jewish leaders after the war as an heroic protector of Jewish refugees and who was the object of testimonials by Golda Meir, the chief rabbi of Rome, and the World Jewish Congress—could have so fooled the very people he had hoped to hurt? Why had no one after the war come up with the evidence which supposedly confirms Pius’s Nazi and antisemitic convictions? The reason may be that Cornwell’s accusations are mostly concocted. Until the victimological hysteria of the present age, moreover, no one would have taken such a work seriously. At least ten magazines, including Atlantic Monthly (which gave the biography high marks), feature a photo of Pius approaching the offices of the German head of state, the entrance flanked by grim-looking soldiers: an obvious attempt to create the impression of an obsequious visit to the German Führer by the papal nuncio. The visit actually took place in 1926, when Pius paid a courtesy call on the democratically elected president of the Weimar Republic.

The real sins of Pius XII, which Cornwell and his adulators find inexcusable, are two. The first charge, having been an “authoritarian” ecclesiastical head, is entirely ludicrous. Any pope, in particular a conservative one, becomes for Cornwell a usable stand-in for Pius IX, who was responsible for the proclamation of papal infallibility at the First Vatican Council in 1870. Unfortunately, Pius XII, a painfully cautious and forever agonized pontiff, was a poor candidate to be Cornwell’s ideal villain: far better for the author to have focused on the autocratic Pius XI, who in fact blasted the Nazis in his 1937 encyclical Mit brennender Sorge, partly prepared by Pius XII. Though Pius XI loathed the communists (and backed the Nationalists in Spain), it would be hard to depict him as a friend of Hitler. The other polluting sin attributed to Pius was to have been hostile to communism and the political left—which allegedly drove him into the arms of the Axis.

If one is a white Westerner, the best way to protect oneself against the pro-Nazi smear is to have had communist or pro-communist associations. For example, both Bella Abzug and the French Communist Party supported the Nazi-Soviet Pact and spent almost two years portraying the Third Reich as no threat to the international working class. Neither has suffered much for this stand (which only isolated historians know about and even fewer dwell on). In comparison to Jewish liberal activist Abzug, Pius XII was an engaged anti-Nazi; unfortunately for his reputation, he also feared the left and enjoyed German culture. Pius XII has suffered a posthumous hatchet job not for being Hitler’s Pope but because he was politically incorrect, undeserving of the proceedings that might have led to his beatification (which, in fact, were halted last October).

In a certain sense, this is fitting. Why should beatification be exempt from the leftist victimology to which every other political—or politicized—event is now subject? Last month, an American television program on the life of John Paul II scolded the Pope (or found someone who did so at length) for canonizing Polish priest and Nazi victim Maximilian Kolbe. Although Kolbe gave his life to save an intended Nazi victim, allowing himself to be executed in the place of a concentration camp inmate with a wife and children, this martyr did not quite measure up to media standards, having made unkind remarks in a Catholic monthly about Polish Jewish commercial practices. These angelic standards would not have been applied so rigorously had Kolbe been a Communist Party member or generic leftist. After all, liberal idol Bobby Kennedy frequently made scurrilous references to Jews and blacks without journalists bothering to mention this habit for 30 years after his death, and even then without hurt to his reputation (cf The Dark Side of Camelot by Seymour Hersch). Pius XII, Cornwell reasons, must have been a Nazi because he held “undemocratic” views about Church polity and the threat communism poses to Christian societies. The Pope also fell short of the special standards applied to non-leftists in determining who is, and is not, an antisemite. Pius’s unkind ethnic reference, during the short-lived Bavarian Soviet regime of 1919, to a Russian Jewish Marxist—a mildly insensitive comment probably easily surpassed every day of their lives by Harry Truman and members of the Kennedy clan—is brought forward to show that the future Pope had genocide on his mind. Right now I have a hard time deciding which is the more reprehensible and

hateful sample of victimological drivel, the teutonophobic fixations of Daniel Goldhagen in Hitler’s Willing Executioners or Cornwell’s collection of factoids. If Cornwell comes off slightly better, it is only because he writes like an educated Englishman. Even among mendacious scribblers, style should count for something.

[Hitler’s Pope: The Secret History of Pius XII, by John Cornwell (New York: Viking) 430 pp., $29.95]

Leave a Reply