The cinematographer, the director’s collaborator and confidant, uses the lens, camera, and lighting equipment to make the fake look real and the real authentic. He creates the visual appearance and style of the film. Freddie Young (1902-98), combining stamina and discipline, was perhaps the greatest cinematographer of the century. The youngest son of a large and recently impoverished English family, he left school at 14 and began as a lab assistant in Gaumont Studios in London. He occasionally served as a stunt man and was injured while filming explosions. Wearing owlish spectacles that seemed to reflect the lens of his camera, he shot horse races and soccer matches. He worked on the first sound pictures in Britain, when noisy hand-cranked cameras had to be placed in soundproofed booths, and sometimes shot three movies at the same time. In his long career, he completed 161 feature films.

Young was a great artist, but he prided himself on being tough, even abrasive with his crew. He emphasized that “you mustn’t let yourself be pushed around by these [studio] executives, no matter how big they are, if you want to protect your reputation as a cameraman.” He worked with famous directors like George Cukor, John Huston, and John Ford. He quotes Ford—guarding the director’s prerogative—saying; “I only shoot what I want to use, to stop the bastards recutting the film afterwards.” Young helped train such future directors as Jack Cardiff and Nicholas Roeg. He won Oscars for filming David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, Dr. Zhivago (both partly filmed in Spain), and Ryan’s Daughter. Though he worked with Lean on three major films, he has very little to say about his character.

This thin, well-illustrated memoir is charming, breezy, and anecdotal. But it’s a great pity Young didn’t start dictating his book before he reached his mid-90’s, when his mental powers and memory had begun to fail. Some of his jokey anecdotes fall flat; others seem to have no point or are even absurd. The actor Walter Pidgeon, for example, living in great luxury, complained that President Roosevelt had “ruined” him, but Young does not explain the contradiction. When the Hungarian director of Caesar and Cleopatra asked Vivien Leigh “if she vill valk jus a lil bit slow,” she meekly followed his orders, yet brashly told Young: “Yes, but you tell Mr. Pascal that I shall do exactly as I please.” Young fatuously remarks of a colleague who had a brain hemorrhage that “when he returned to the studio he was a sick man.”

Many of Young’s descriptions are superficial. He calls the English producer Ivor Montagu “a terribly nice, gentle sort of chap” (in true Hollywood fashion, everyone is simply wonderful), and blandly observes that he “found the customs of Japan fascinating.” But he doesn’t say anything about die emotional dynamics of filming a love scene with Sarah Miles in Ryan’s Daughter.

Young does tell several good stories that reveal the glamorous and adventurous aspects of filmmaking. Lean took his Rolls Royce wherever he was working, and Tyrone Power outdid him by transporting his yacht to Europe on an ocean liner. Filming Richard Brooks’ Lord Jim—”a hotchpotch of every film you’ve ever seen: a bit of piracy, mysticism, love interest”—in the jungly ruins of Angkor Wat in Cambodia in 1964, Young experienced (as I did when visiting these crumbling monuments two years later) swarms of locusts that dived into his food and drink. Like Young, I sealed the crack under my hotel room door at night and climbed under the mosquito net. The locusts simply crawled through the drainpipe of the sink and flew above my head. Slashed by the ceiling fan, they formed a crusty carapace when I stepped barefoot onto the floor the next morning.

This memoir, with its many technical details, shows the evolution of camera work throughout this century and reveals Young’s main (though undefined) theme: his ingenious solutions to many difficult cinematic problems. Throughout the down-to-earth book, he stresses trade secrets and the practical details of how illusion is created, rather than aesthetic questions. Young made the snow in Dr. Zhivago (insufficient even in the coldest part of Spain) from hundreds of tons of marble dust. He made the ice out of candle wax and formed the slippery patches with a laver of soap. He put rock salt on the actor’s coats and shaving cream on their beards, and made their breath seem cold by having them exhale cigarette smoke. Young achieved a flattering halo effect around the face in a close-up “by stretching a piece of white gauze over the camera a few inches in front of the lens, then using a lighted cigarette to burn a hole in the centre of the gauze.”

He shot aerial combat by hanging miniature Spitfires on invisible nylon cords and gave the actors the illusion of weightlessness on a moon made of plaster by having them bounce on trampolines while he filmed them in slow motion. Young blew up houses by rigging “up a wood and plaster set that is deliberately flimsy, with the timbers half sawn through. [He drilled] holes at strategic places, put dynamite in them, and wired all the charges with one switch beside the camera. When the switch is pulled the whole thing is blown apart, collapses and bursts into flames.”

Freddie Young’s two most challenging achievements were filming the storm in Ryan’s Daughter and the mirage in Lawrence of Arabia. Instead of shooting the storm with fire hoses and wind machines, the crew filmed a real tempest on the rugged Irish coast. “We were all in wet suits,” Young told Lean’s biographer Kevin Brownlow (who preempted some material from Young’s unpublished manuscript). “The camera was chained to a rock and it was as much as you could do to hold on to the tripod and crouch against the wind.”

Suggesting the burning cauldron of the mirage shot. Young told Brownlow that, when filming Lawrence of Arabia in the Jordanian desert, “Light conditions were a constant surprise, and peculiar phenomena such as spirals of sand, called dust devils, would arise from the desert and, whirled by some heat currents of air, travel rapidly at us in a long sideways column, taking sunshades and other paraphernalia with them.”

In his own book, Young explained how he managed to capture the illusion with a special lens: “A mirage in the desert is always seen in the distance, looking as though the sea is lying on top of the sand. With a telephoto lens you can film this in close-up, which enables the audience to see details of the heatwave and the blueness invisible to the naked eye.” On the screen, you see “first the mirage, then on the horizon a shimmering dot of a figure. As he comes closer you get a distorted image of his camel trotting, it seems, through water, and finally a clear view of Omar Sharif [playing Sherif Ali] approaching the last few yards.” The mirage not only dramatizes the appearance of Sherif Ali as Lawrence and his Bedouin guide rest at the alien watering hole, but the three-minute, almost-silent sequence leads to a violent confrontation and illustrates the fierce passions of the desert—perhaps the most stunning sequence in the history of cinema. Nowadays, Young regretfully observes, so many visual effects are done digitally in postproduction that a great deal of creativity has been taken away from the cameraman.

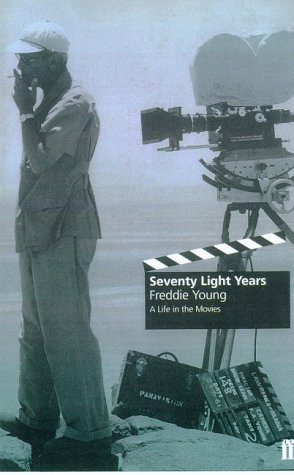

[Seventy Light Years: A Life in the Movies, by Freddie Young, as told to Peter Busby (New York: Faber & Faber) 164 pp., $27.00]

Leave a Reply