The- Missouri Ozarks are the western outpost of Appalachia. The hills are not as high as their elder brothers to the east, but they plunge down into narrow, labyrinthine valleys, where streams of cool, green water run. The surrounding soil is mostly shallow and full of rocks, with open spaces so small that vegetable gardens are the only farming. Those hills that have not been denuded of their timber are covered in lush and beautiful hardwood forests. In the summer, they are almost impenetrable; once inside, there is deep shade and a cacophony of sound—a chorus of cicadas, the thump-thump-thump and wild cries of pileated woodpeckers. In the winter, the trees are stripped bare by ice storms, and the forest floor is carpeted with oak leaves.

The Ozarks are beautiful, but one can feel claustrophobic and trapped by them, and their human communities are isolated and somewhat cut off from the larger world. They remain a poor rural backwater inhabited by fiercely independent and often violent clans. Today, the chief occupation of the men appears to be growing marijuana and cooking methamphetamine. The chief means of escape is joining the Army.

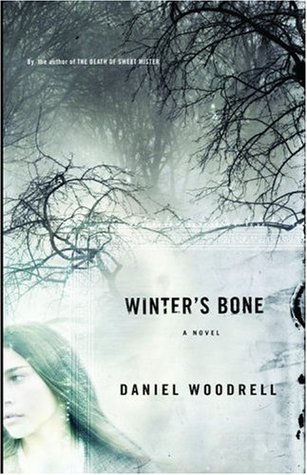

Daniel Woodrell is from this place, and he lives there still. Those who have not read his books may yet know something of his work. The excellent screenplay for Ang Lee’s underappreciated 1999 film Ride With the Devil, about a band of Missouri Confederate guerrillas, was adapted, often word for word, from his excellent 1987 novel Woe to Live On. He has set his latest story in the coldest part of an Ozark winter when clouds can be seen “splitting on distant peaks, dark rolling bolts torn around the mountain tops to patch the blue sky with grim,” and “the bringing wind rattled the forest, shook limb against limb.”

The bleak winter landscape mirrors the ordeal of Woodrell’s heroine, 16-year-old Ree Dolly, whose father has disappeared, whose mother has gone crazy, and whose two younger brothers now look to her for provision, protection, and permanence. Woodrell’s lyrical and evocative sentences quicken both physical and mental worlds. “The snow fell first in hard little bits, frosty white bits blown sideways to pelt Ree’s face as she raised the ax, swung down, raised it again, splitting wood while being stung by cold flung from the sky.” “Coyotes howled past dawn, howled from far crags and ridges and down the valley to the end of the rut road where the school bus stopped.” “In the house she slept, and when she woke the sun was red falling west and everybody wanted food.”

Sometimes, all she has to feed Sonny and Harold are “oatmeal suppers,” but there is episodic help from neighbors and family—and hunting. Ree teaches her brothers how to shoot rifles, then takes them into the woods in the early morning to pick off squirrels. “Ree and the boys sat with their backs propped up against a large fallen oak, butts on gathered leaves, boots in thin patches of snow. . . . The needed skill was silence.”

The real drama begins when Ree learns from the deputy sheriff that her father, a skilled cooker of “crank” (meth), has used their house as collateral for a jail bond and is now missing. If he does not turn up in a few days, they will lose the house, its land and trees, and the family will be scattered. Were that to happen, Ree would fare the best, for she is only a year away from being old enough to join the Army, which has been her plan anyway. Instead, she decides to look for her dad, knowing the danger of asking questions of extended family who are likewise involved in the drug trade (and sometimes worse things) and knowing also that she has an easy way out. She chooses the harder, but better, way. Ree, it turns out, would rather stay home, care for her two brothers, and revel in the beauty of her wooded and rocky hills than patrol the sanguinary streets of Baghdad.

Writing of William Faulkner, Russell Kirk observed that

the writer may write much more about what is evil than about what is good; and yet, exhibiting the depravity of human nature, he establishes in his reader’s mind the awareness that there exist enduring standards from which we fall away; and that fallen nature is an ugly sight.

In Woodrell’s Ozarks, even the land is fallen. Forests on private land have mostly been cut down. Ancient springs are poisoned. (“Stuff has leaked to the heart of the earth.”) The soil is barren. Immorality abounds. Infidelity and drug abuse are rampant. There are few good jobs. Both community and family are dysfunctional, yet we cannot help noticing that it is a community—unlike exurban America, which is no community at all. We also cannot help noticing that, while Ree has to grow up too fast, more affluent American adolescents hardly grow up at all, and that, if her family suffers from material deprivation, wealthier families suffer from a deprivation that is normative and spiritual.

As in so much Southern fiction, that other, spiritual world is ever present. Before her mind broke and the parts scattered, Ree’s mother would sometimes beat her with a rake while hung over and depressed after a night of that all-American pastime, “partying.” But one day, an “unsmiling angel pointing from the tree tops” put an end to that. God may seem to have abandoned His world to the wickedness of men, but He hasn’t. And a better world beckons. The boys ask Ree to describe Heaven: “Sandy. Lots of fun birds. Always sunny but never way hot.”

[Winter’s Bone: A Novel, by Daniel Woodrell (New York: Little, Brown and Company) 193 pp., $22.99]

Leave a Reply