That the republic has degenerated from a Protestant-inflected localized republic to a centralized bureaucratic imperial state is something most conservatives take for granted. The reason for such a transformation, however, sometimes becomes more assumed than proved. This compounds the difficulty of convincing liberals, and even some “conservatives,” that such a transformation has occurred. The secular Whiggism of the major media outlets and academia is so overwhelming that actual American history is obscured or willfully ignored. Since the 1960’s, the aggrandizement of the central government and the judiciary by both parties has effectively effaced real federalist checks on national power. Local differences in political habits or mores are treated with suspicion or as obstacles to “rights” rather than as a support for liberty.

Even among conservatives this history is largely unknown despite three decades of “conservative dominance” of the Republican Party. The establishment conservatism of the Beltway and Wall Street similarly see centralization as inevitable, though for them it is usually hidden behind the economic language of “efficiency” or culture-war language that mirrors the ideological obsessions of the left. Invocations of federalism, as in the gay-marriage debates, are not serious because judicial interference or executive orders are invoked on subsequent issues, if such would further a political agenda. There are some exceptions, of course. The Southern Agrarians were strong proponents of federalism. Russell Kirk wrote important pieces on federalism and Orestes Brownson’s view of “territorial democracy.” More recently, Bill Kauffman has excavated a regionalist antiwar tradition of which more conservatives should be aware, and others, such as Gore Vidal, have focused on the depredations of Washington.

The general neglect of what is perhaps the most distinctive American contribution to political thought is curious because, as Jeff Taylor notes, “Americans have traditionally been suspicious of highly centralized government because it tends to be directed by remote elitists and administered by remote bureaucrats.” Both the Tea Party and the Occupy movement represent aspects of what has long been mainstream American opinion on government, money, and the role of each in a republic:

Both are frustrated with a corporate-dominated status quo where Washington seems to be a rigged game while the middle class—or the 99 percent—are given empty promises by politicians who are discreetly leased by a financial elite.

The objects of their opposition may differ, but they both reflect a long-standing American distaste for the centralization of power. Unfortunately, the two movements share another characteristic all too common in American opposition movements: Both are in the process of being completely taken over by the organs of the political establishment and the financial interests that support the establishment.

For Taylor, decentralism comprises four elements: democracy, liberty, community, and morality. Thomas Jefferson is initially the central figure here, as his work includes aspects of all four of the decentralist elements; Taylor explains why this makes Jefferson of continuing importance to the American political conversation. In a sense, Taylor bases his history on the classic Jeffersonian-Hamiltonian dichotomy. There remain two ways of seeing America, and where many pundits and politicians use Jeffersonian rhetoric, Taylor exposes the Hamiltonian language underneath.

Federalism is a useful term, but the perspective Taylor delineates is broader than a simple adherence to the division of power between the national government on the one hand and state governments on the other. Rather, it means “minimalistic government at every level.” It is a liberty-biased perspective that provides the overarching principle of particular decisions and arrangements of government power. The people who hold a decentralist position range from ethnic enclaves who want to preserve their cultures to secular liberals; as Taylor notes, the arguments for decentralization have appeal across the spectrum, in part because these arguments transcend that spectrum.

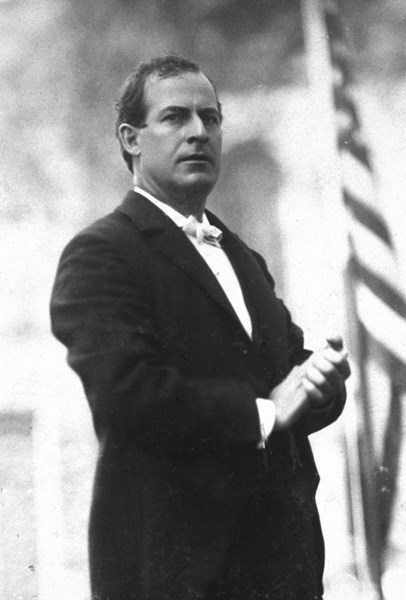

Taylor is charitable to all sides, and he acknowledges the disasters of the American experiment in regionalism, including Jim Crow. He resists demonizing those who sought greater centralization or to destroy communities; such results need not have been a reflection of evil motives. Nor is there an easy urban-rural divide to draw. Although in some circumstances rural life tends to reinforce those virtues and habits supportive of Taylor’s four elements, that need not always, or exclusively, be the case. Indeed, given the desolation of America’s rural communities in the present day—thanks to the centralization the great Midwestern tradition embodied by William Jennings Bryan and Robert La Follette tried to stem—towns and other urban areas may be more fertile sources of decentralist resistance right now. Taylor’s analysis is generous enough to include this possibility, as well as to give respectful attention to progressive or other movements whose aims are inspired by decentralist ideas.

Decentralization is no sure cure for political ills, but that is the point. Government power—contrary to fantasists of both parties—cannot solve all human problems, nor cure the effects of original sin. The argument for widely dispersed power is prudential as much as principled. “The existence of a multitude of small-scale sovereignties provides for avenues of individual escape if community reform cannot be achieved.” Having many points of government power reduces the malevolent reach of any one of them. It is a simple truth that has been sent down the memory hole, replaced by the assumption that individual wants must trump, with government power if necessary, the considered views of the community; and that these wants, moreover, must be uniformly enforced across the nation.

This book is engagingly written, and the notes and source materials would provide the raw materials for a true conservative renaissance. The text itself, after an introductory chapter setting the stage, is divided into eight chapters tracing the decline and fall of the decentralist ideal in each of the major political parties, as well as three appendices dealing with William H. Murray and George C. Wallace as “other populists with national ambitions,” Woodrow Wilson, and the tale of Thomas Bayard and Grover Cleveland.

Perhaps the high points in the political influence of the American decentralist tradition occurred during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and again just after World War II. In a chapter titled “The Path Not Taken by the Progressive Era and New Deal,” Taylor discusses the Jeffersonian tradition as it was embodied and sustained by the once immensely popular but now almost forgotten Bryan and La Follette. These men were progressives, but not progressives as we understand them; no proponents of the modern welfare state (as they are often claimed to be), they were rather “Midwestern agrarians [who], being populists, disliked unnatural largeness in the economic and political spheres.” Taylor carefully documents how important progressive goals were subverted by the centralizing impulse. Thus, history books credit—when they mention them at all—progressives like Bryan with the crusade against the trusts. That may be true, but the federal agencies and laws established to fight the trusts worked against the progressives’ goals, which were to disperse the power of enforcement in order to prevent the trusts from doing what they eventually did—control agencies like the Federal Trade Commission and, at a financial level, the Federal Reserve. “[O]ne wonders,” Taylor wryly notes, “if occurrences of bait and switch can really be tallied as wins for the agrarian movement.”

The Southern Democrats, perhaps the most Jeffersonian wing of their party, maintained this tradition the longest, by Taylor’s estimate through the 1970’s. But they too have largely succumbed, in part because of their own centralizing compromises but also because even

when they were at their most conservative they often expended their political capital to conserve the worst of their traditions. By invoking states’ rights in defense of segregation, they used an honorable means for a dishonorable end.

Indeed, the unimaginative recalcitrance of Southern conservatives on civil rights has perhaps been the most severe blow to the decentralist cause, and any evocation of states’ rights or federalism remains tainted, even when it is used by those with no connection with, or interest in, the South.

Taylor is no less sparing in his assessment of the Republicans: “Decentralization of power—at home and abroad—is not a priority for most Republican administrations and legislators because they like power . . . as long as it is wielded by themselves and their allies.” They too battled intramurally over what kind of America they stood for. On the one hand was the Eastern financial and political establishment, represented by such figures as Wendell Willkie. This wing has triumphed, perhaps permanently, over the more conservative segments of the party. In retrospect, the Reagan years have made no difference at all and indeed may have made conservatism’s position worse, Reagan having cloaked even solid conservative impulses in universalist rhetoric lifted from Thomas Paine.

As an historian, Taylor can be said to argue simply not to put your trust in princes. Elites, especially Eastern elites, will always choose centralized power over geographical and political diversity. But the other crucial contribution Taylor makes is to draw the connections between and among the men and women who have decided America’s fate. Elite Americans sometimes like to believe that abstract principles govern human affairs: “equality,” perhaps, for the left, and “capitalism,” typically, for the right. Taylor acknowledges the force of ideas, but it makes a difference when these ideas are discussed, and by whom. That George W. Bush’s Cabinet was composed of men of his father’s era, who shared old connections with the Eastern Republican establishment, is significant. That Rockefeller interests were so closely intertwined with one of the nation’s largest banks over generations is important. Taylor, without unduly attributing people’s views solely to their backgrounds, nevertheless puts in fuller context the facts of how political change is effected in this country. This is humane history, in other words, which paints the individual at the center of historical change.

Politics on a Human Scale is both solid history and inspiring polemic. Although as an historian Taylor takes a pessimistic view, he retains a Christian hope that the current moment provides an opportunity to revive a humane political tradition. Let us hope that he is right.

(L: Robert La Follette, Sr.; R: William Jennings Bryan)

[Politics on a Human Scale: The American Tradition of Decentralism, by Jeff Taylor (New York: Lexington Books) 629 pp., $54.99]

Leave a Reply