Anyone writing a novel about thoroughbred racing in Kentucky would think first of setting it at Churchill Downs—that brassy track in Louisville which holds its tinsel-television spectacle of the Kentucky Derby every May. Instead, Alyson Hagy chose Keeneland, Lexington’s track set in the middle of the Bluegrass horse farms. Keeneland is smaller, greener, more pleasant in every way, and it’s a quick trip from the stands back to the paddock to see the horses as they saddle up for the next race, something that for me is always the best part of the racing day. Only recently did Keeneland get an announcer (the equivalent, for you Cubs fans, of installing night lights at Wrigley Field); and races run in that now-lost relative silence had a greater charm, too. hi her choice of setting, Hagy avoided the obvious for the more interesting: an early sign to the reader that her novel will be a good one.

With its hats and clubhouse pins, its incomprehensible racing form, its exactas and boxed bets, the ritual (and to many it is precisely that) of going to the racetrack has never had much allure for me, though you’re not supposed to admit it when you’ve grown up a few miles from the Downs. What I do understand is the appeal of the horses. Alyson Hagy feels it too, which is why she has set her novel not in the “upstairs” of thoroughbred racing, among the owners in the stands, but in the downstairs, the backside, where the horses are exercised and timed, closely watched and understood by a very different group of people.

The novel is told in the voice of Kerry Connelly, an exercise rider who has come to Lexington to work the spring meet, on the run from a husband in New York who is up to his chin in dope and loan sharks. She has beelined to the place she calls home—not Frankfort, Kentucky, where she finished high school, nor her mother’s place in Florida, but the track where she first made something of a name for herself, before leaving with a man she loved and falling flat. At Keeneland, she hopes to hide for a while, work enough to eat, and sort out her feelings.

Kerry is a compelling character, and the string of bad decisions she makes only places her essential integrity in sharper relief. In punishing herself for her mistakes, she does the job thoroughly alienating her old friends, losing her earnings at poker, allowing herself to be sweet-talked into a scam, getting beat up. Living among the racing equivalent of carnival people, Kerry has learned to like the roughness. Owing to Kerry’s trueness and resilience, though, the story is less gritty than a quick synopsis makes it sound. All this self-punishment is part of her healing: She tells herself at one point that she doesn’t deserve to work for her old friend Billy T., but has to earn a new future for herself, without help. Even as her circumstances worsen, she finds first hope, and then salvation. This is not a “Christian” novel, but it is a pilgrim’s progress, a character study of a good woman trying to make sense of a world whose mix of betrayal and grace is recognizable to all of us, backsiders or not.

Kerry takes great care of her mounts. She reads them better than their trainers do, being a lot like a smart, high-strung mare herself Her transcendent feelings during her dawn rides are instantly recognizable to anyone who, on the back of a horse, has felt something similar; these passages are beautifully written, evocative, and show the depth of spirit Kerry is capable of—when not snatching at the seemingly shortest way out of trouble, which, like most shortcuts, isn’t.

Another pleasure of this book is the care with which it is written; well-paced, it ends just as it should. Hagy’s minor characters are nicely drawn, too: among them Reno, the boy preacher turned stable foreman who sermonizes to his horses; Alice, a mid-level trainer fighting to keep her barn in business; and Red Flora, the jockey agent, always positive, always anxious, whose young clients always ditch him in the end.

Capturing the protagonist’s voice, however, is Hagy’s real accomplishment. Kerry is a character who rings true: not just as an individual but as a representative of an entire late-century generation of 20-somethings. We live in hard times, and the Kerrys of this world will need a good seat, light hands, and plenty of grit in order to ride them out.

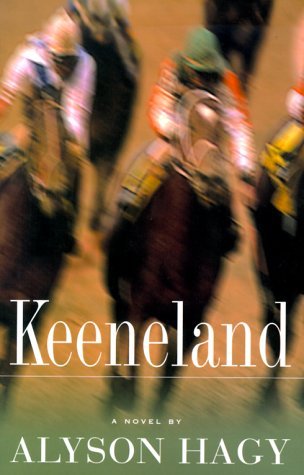

[Keeneland, by Alyson Hagy (New York: Simon & Schuster) 270 pp., $23.00]

Leave a Reply