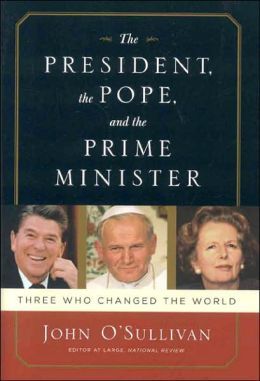

According to John O’Sullivan’s version of recent history, in the fullness of time, three great conservative leaders—Ronald Reagan, Pope John Paul II, and Margaret Thatcher—came unexpectedly to occupy positions of power, to shatter post-World War II orthodoxies, to facilitate the collapse of the Soviet empire, and to make the overall revival of their institutions and societies possible.

In the preceding decade, according to the author, the three were “middle managers” in their respective establishments, disgruntled with the 1960’s consensus (détente, Vatican II, Keynesianism) that enabled liberals of different hues to dominate “debate and the general direction of policy even when they were out of power.” While even political and religious traditionalists sought “subtle and ingenious leaders” who could divert modernist challenges into orthodox channels, Wojtyla, Thatcher, and Reagan “all embodied such fading virtues as faith, self-reliance, and patriotism—which the modern world seemed to be leaving behind.”

The manner in which the three succeeded in making it to the top against all odds and then “changing the world” is, in O’Sullivan’s rendering, a morality play wrapped in a quickie book. There is Providence, saving them from assassination attempts. There is harmony, prompting them to join forces in the “miraculous” peaceful liberation of Eastern Europe from Soviet communism. There is faith, enabling them to become, in the words of the publisher’s blurb,

beacons of optimism cutting through the malaise and despair that afflicted 1970s America, strike-ridden and economically moribund post-imperial Britain, and a Catholic Church rocked by social and sexual revolutions.

And the end result was a reinvigorated West.

Once the outline is in place, O’Sullivan picks and chooses, sometimes cleverly, the tiles to fit into his preconceived mosaic. We follow Reagan’s, Thatcher’s, and Wojtyla’s presumed maturation as strong leaders. Their key moments are said to be the pope’s visit to his native Poland in 1979; Thatcher’s resolute response to the Falklands crisis in 1982; and Reagan’s adoption of Peace Through Strength embodied in the Strategic Defense Initiative.

O’Sullivan’s approach reflects his inability to distinguish between the factual truth of who did what to whom in a highly complex decade, and his version of a “higher” truthfulness. The result is a collection of overextended essays that is historically inaccurate, analytically inadequate, and biographically oversimplified. As a 3,000-word National Review article, the compendium could have become a quaintly Rankean piece of highbrow journalism. As a book, however, The President, the Pope, and the Prime Minister fails to inform, enlighten, or even amuse.

When it came to the trio in question, there was always less than meets the eye. The proof of the smoke, and the absence of real fire, lies in their legacy. The Catholic Church is not in good shape, as Pope Benedict XVI is all too painfully aware. Reagan and Thatcher were followed by nonentities (John Major), state-capitalist establishmentarians (George H.W. Bush), malevolent crooks (Bill Clinton), velvet-gloved totalitarians (Tony Blair), and dangerously deluded millenarians (George W. Bush). All three had their conservative moments and conservative aspects, but none was a Great Conservative Leader. It may be far too early to judge their overall impact, but it is preposterous to assert—as O’Sullivan does—that it had a world-historical significance.

O’Sullivan’s treatment of Margaret Thatcher, in particular, borders on a Politburo-approved hagiography. (For a more accurate account, see the late Sir Alfred Sherman’s Paradoxes of Power: Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude, which came out in paperback last March.) Her “legacy” is a postmodern, self-loathing Britain on the fast track to cultural and demographic self-annihilation.

As we know through 16 years of hindsight, the collapse of the Soviet Empire was, above all, a crumbling from within brought on by the rush to reform. Gorbachev’s motives were primarily domestic and economic. His rationale for embarking on glasnost, and the manner in which perestroika subsequently escaped his control, were affected, but by no means determined, by the challenges posed by Solidarity (Wojtyla) and America’s rearming (Reagan); Thatcher and her little war in the South Atlantic were utterly irrelevant.

Whether a truly great pope and an equally great American president (forget prime ministers) may yet stem the tide and “change the world” is uncertain. What is certain is that the Western world is in peril and needs changing.

[The President, the Pope, and the Prime Minister: Three Who Changed the World, by John O’Sullivan (Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing) 448 pp., $27.95]

Leave a Reply