When Chronicles asked me to provide a refutation of Donald Trump’s 1776 Commission report (“Rejecting the ‘Proposition Nation,’” April/May 2021), I knew it would be controversial. I was right. Michael Anton wrote a lengthy rebuttal at American Greatness (“Americans Unite,” May 1, 2021). I don’t mind Anton circling the wagons to defend his friends. That is admirable. That said, his attacks on my piece require a rebuttal, both to defend my positions and to parry his assertion that I am defending slavery and racism.

The main point of my contribution to Chronicles was to illustrate how men like Anton give aid and comfort to the left. Therefore, I stated:

The attempt by the authors of “The 1776 Report” to beg absolution from the political left for the sin of slavery is a fatal miscalculation. The left’s game is to cancel culture, and it’s a game in which conservatives will always be playing catch-up. You cannot play the left’s game on their field and by their rules and hope for success.

Conservatives like Anton consistently choose longtime heroes of the left, like Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King, Jr. This is a calculated move, but one that will never have the desired effect. These conservatives believe that if they can somehow convince enough Americans, left and right, to view “equality as a conservative principle,” as Harry V. Jaffa wrote in 1975, or Martin Luther King, Jr. as a conservative (as Anton suggests in his book The Stakes), then Americans will come to embrace them as sober revolutionaries in a common American enlightenment. Presumably, some believe such a strategy will stop the headlong rush to woke “social justice.” It has not worked and never will work. The left’s reaction to the 1776 Commission report is evidence enough. As the Southern theologian R. L. Dabney pointed out in 1871, “American conservatism is merely the shadow that follows Radicalism as it moves forward towards perdition. It remains behind it, but never retards it, and always advances near its leader.”

The left “is coming for both our throats,” Anton correctly states, but this is at least partly because Lincoln opened a Pandora’s box in his 1863 Gettysburg Address. The address was panned at the time by more cautious souls, but has been elevated to near religious reverence by the “Claremont/Hillsdale School,” which Anton refers to as the CHS.

Anton and his CHS friends disregard the paleoconservative belief that Lincoln is central to the establishment of the modern American imperial state. I have argued in several publications that Lincoln’s role in transforming the executive branch and the Constitution denatured the original federal republic.

But that was not the focus of my recent Chronicles piece. The CHS argument, and by default the 1776 Commission report, makes Lincoln central to the American experience because as president he codified the “proposition nation” myth. “Invented” would be a better term. And it was Lincoln’s Declaration—not the original Declaration of Independence—that formed the spine of the 1776 Commission’s report.

In any case, Anton does not want to grasp that the Declaration (whether the Jeffersonian or Lincolnian version) is not the founding document of the United States. Thus, Anton ahistorically asserts that the Declaration “is literally the document that founded the country … the first organic law of the United States.”

On the contrary, as historian Pauline Maier asserts in her book American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence, the Declaration was in fact a “de-founding” document. It would be better to classify it as a secession document that formalized the separation of 13 “Free and Independent States,” from Great Britain. No unified American nation state existed in 1776. Virginia and Maryland had already declared their independence before the Declaration was signed, and it took several years for the American States to agree to a formal Union of States. John Adams referred to the delegates to the Continental Congress as “Ambassadors.” That central authority had little to no power over the constituent members of the Union, a problem the Constitution sought to rectify more than a decade later.

More importantly, the argument that the Declaration created the “first organic law of the United States” is incorrect. It did not form a government or create any legislation. If it was “organic law,” as Anton submits, there would have been no reason for the states to draft separate constitutions or for the Continental Congress to produce the Articles of Confederation. The Declaration should have been sufficient. And good luck using the Declaration as a defense in a court of law.

It is true that some states adopted similar language in their declarations of rights—Anton points this out as a “gotcha” moment in his article—but that’s not the entire story. While he’s correct that the word “equality” can be found in several state declarations, he omits much of the language. New York, he says, lifted the line “all men are created equal” from the Declaration. That is true, and following Anton, one might think this is the only line that the people of New York transcribed from the Declaration, and that it was, therefore, the most important “fundamental principle” of government in the founding period.

In fact, New Yorkers copied the entire Declaration into the 1777 New York Constitution because they considered the document to be a “cogent” argument in favor of separation from Great Britain, and they would defend it at all costs. In other words, the principle of independence articulated in the Declaration is what made it meaningful to New Yorkers, not its lofty egalitarian rhetoric. Context matters, as does the qualifying language in the documents Anton cites.

Moreover, the New York legislature continually blocked emancipation bills in the years after the War of Independence because they did not want blacks to vote. Given this fact, one must question how committed the founding generation really was to the principle of “equality.” In fact, the historical evidence leads me to believe that the founding generation, and even Jefferson, “downplayed” the “proposition nation” that Lincoln later elevated to the status of religious dogma.

Connecticut, for example, rejected emancipation in 1777, 1778, and 1779, and only accepted it in 1784 on a compensated and gradual basis. It also barred blacks from voting in 1818, which was the same year it ratified the Declaration-inspired language “all men when they form a social compact, are equal …” If that phrase meant that blacks were equal in Connecticut, why couldn’t they vote?

Ohio outlawed slavery when it became a state in 1802, but quickly passed exclusionary laws. Black Americans who wished to live in Ohio had to pay a $500 bond (equivalent to roughly $12,000 in current-day dollars) that guaranteed “good behavior.” This financial penalty effectively kept blacks from settling in Ohio. But sure, these Ohioans believed that all men were born “equally free and independent.” Unless, of course, a black man and his family wanted to live in their state.

The Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 came close to carrying the same meaning of the “all men are created equal” phrase in its declaration of rights, not coincidentally because it was written by John Adams, who served on the committee that drafted the Declaration. In 1778, however, the Massachusetts legislature had drawn up a constitution that made slavery legal in the state and prohibited free blacks from voting, which is not a ringing endorsement for Anton’s claims that the founding was “non-racist.” That constitution was rejected, but not because of its pro-slavery language: blacks still couldn’t vote in Massachusetts even after the 1780 document was ratified.

Only New Hampshire and Vermont had strong enough antislavery majorities to outlaw slavery and allow blacks political and civil rights in the founding period. Yet abolitionists were violently assaulted in New Hampshire in the early 19th century when they attempted to provide integrated schools.

As historian Barry Shain correctly notes, “the persistent record … of the colonists’ denial or narrow restriction of the rights of Roman Catholic Canadians, Native Americans, African Americans, loyalists, Quakers, and, to a lesser degree, other British colonials in Ireland, the West Indies, and elsewhere necessarily places in question the centrality of the soaring, liberal, universal rhetoric of the Declaration.”

Jefferson’s own understanding of the Declaration provides little support for the view propagated by Lincoln, Anton, and the CHS School. As he wrote to Continental Army Major-General Henry Lee in 1825:

[T]his was the object of the Declaration of Independence: not to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of, not merely to say things which had never been said before; but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject; … terms so plain and firm, as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independent stand we are compelled to take.

Even the author of the document did not believe the Declaration contained any “new principles” or “new arguments.” For Jefferson and the Founding Fathers, independence trumped other principles. Jefferson’s commitment to federalism was the driving force in his political philosophy, as biographer Kevin R. C. Gutzman shows in his book Thomas Jefferson—Revolutionary: A Radical’s Struggle to Remake America. Jefferson’s views on race never approached modern conceptions. Blacks were “inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind,” Jefferson wrote in 1784, eight years after contending that “all men are created equal.” He was quite clear that he never really wrestled with equality and considered it a foregone conclusion that whites and blacks were not equal.

Anton and the CHS School live in a fairy tale world of racial egalitarian Founding Fathers who all yearned to end slavery—the historical record be damned. This self-deception allows the left to punch holes in their bad arguments. Fabricating a “usable” and politically correct past is a typical strategy of the left, but it is not an activity that the right does very well.

The CHS School and its founding historian, Harry V. Jaffa, go through great mental contortions to foist a Lincolnian definition on the Declaration’s use of the term “equality.” If we want to rely on the words of two prominent members of the founding generation, John Adams and Alexander Hamilton, then the equality these men advanced could be condensed to one phrase: “exact equality of constitutional rights” for Englishmen. This did not mean social, racial, or even political equality. George Washington, who led the War of Independence, would have agreed. The United States offered little radical departure from the antebellum status quo in most states.

If the founders were racist and more proslavery than he and other CHS School intellectuals and neoconservatives insist, asks Anton, can we still admire them? His answer would be no. Turning that question in a different direction: How can Anton admire and worship the white supremacist Abraham Lincoln, who up until the Civil War hoped to resettle American blacks in Haiti?

The founding generation may have been the greatest generation in American history. They wrote two constitutions for the United States; led the States to victories in two wars over the greatest imperial power in the world at the time, Great Britain; authored over a dozen state constitutions; and formed most of our political and legal institutions. That they were or were not racists or slaveholders is irrelevant. The response should be “So what?” Projecting contemporary moral standards onto the past is the left’s game, and conservatives should respond with logic rather than fantasy. We admire people from other slaveholding societies throughout history. This doesn’t make us pro-slavery or pro-racism. It makes us objective.

Another issue that needs to be addressed is Anton’s ill-informed discussion of John C. Calhoun. He supports the common CHS view that conflict between North and South might have been resolved peacefully had it not been for Calhoun and his “positive good” thesis of slavery. This is to vilify Calhoun with a blame he does not deserve. Calhoun was hardly the first to defend the merits of slavery. New England theologian Theodore Parsons articulated a “positive good” thesis about slavery in 1773, more than 60 years before Calhoun gave his “positive good” speech in Congress. And Parsons wasn’t alone. As historian Larry Tise explains in his book Proslavery: A History of the Defense of Slavery in America, 1701–1840, “nothing was unique about the defenses of slavery uttered in the South during the 1820s before [abolitionist William Lloyd] Garrison. No one offered a single argument that had not already been used in substantially the same positive language in colonial America, in Britain, in the West Indies, or even in the Northern United States early in the nineteenth century.”

Calhoun’s pro-slavery sentiments are the least interesting part of his public life. They do not explain why conservatives, from Russell Kirk to Richard Weaver, admired Calhoun. Kirk did not include Lincoln in his book The Conservative Mind, but he featured Calhoun prominently because Calhoun had advanced the political principles of American conservatism—most importantly the view of the Constitution as a “negative document,” or a series of “no’s,” as Weaver has explained. Libertarian scholar Murry Rothbard echoed this sentiment even though he verbally impaled Southern slaveholders for their defense of slavery.

In other words, you can separate Calhoun’s defense of slavery from his important contributions to conservative political philosophy. The spokesmen for the CHS School disagree, much to the detriment of American conservatism.

Anton contends that “McClanahan dances around the question of slavery. He never defends it but also declines to condemn it.” Why would I condemn something just to condemn it? I don’t know anyone who is pro-slavery in 2021, unless you count those establishment thugs in Washington, D.C., who want to saddle us with more oppressive government. Do we need to offer a blood sacrifice to appease the high gods of wokism every time we discuss that “peculiar institution”? This attitude gives the left power, but conservatives none.

Anton faults my explanation of antebellum American politics because I failed to mention the “single most important cause of the Civil War: the dispute over the expansion of slavery into the federal territories destined to become states.” That was not the point of my Chronicles article, and Anton is clearly reaching hard for accusations.

What exactly was the core reason for the dispute that led to the Civil War? A moral crusade by nonracist Northerners to eradicate slavery? A racist South seeking to expand slavery to keep blacks oppressed? Neither. As the various Northern secessionist movements before 1830 make evident, the key to antebellum American history was the struggle for power.

As early as 1794, leaders in New England began pressing for the independence of their region, not because they despised slavery, but because they saw no chance of winning federal elections. They continued with their project through Jefferson’s and Madison’s administrations and only ceased to advance secession because of the political backlash caused by the secessionist Hartford Convention of 1814–15. Western territories meant new states, and new states, free or slave, meant control of the Senate and the general government, and control of the general government meant political and economic power. The North’s complaint about the “three-fifths compromise” and “slave power” expressed a political concern.

above: the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D. C. (Henk Meijer/Alamy Stock Photo)

Anton also conveniently omits that Lincoln’s Republican Party frequently relied upon racist arguments to push its platform. It was the party of free white men, free white labor, and free white soil. David Wilmot, Republican United States Senator from Pennsylvania (1861–1863) and Lincoln’s nominee to the Court of Claims, famously said in 1846 that he opposed slavery in the territories in the name of “free white labor a fair country, a rich inheritance, where the sons of toil, of my own race and own color, can live without the disgrace which association with negro slavery brings upon free labor.”

Anton’s claim that the early Republican Party favored immigration restriction is questionable. The Republican Party platforms of 1860, 1864, 1868, and 1872 all favored unlimited immigration, and it was a Supreme Court dominated by the party of Lincoln that foisted the Wong Kim Ark decision on the American public in 1898, a case that decided in favor of the legal status of a child of immigrants from China, which codified birthright citizenship.

Anton concludes his remarks by calling my Chronicles piece a “rhetorical disaster” that will have the earth-shattering effect of giving the left the opportunity to condemn the right as “anti-equality” and “pro-slavery.” When has the left not done this? To believe the left would cease their practice of name-calling after reading the 1776 Commission report is delusional.

The Biden administration scrapped the 1776 Commission report upon coming into office because they don’t believe it, and, to some extent, rightfully so. The report was based on bad history and an incorrect assessment of the real founding: in liberty, not equality; federalism, not nationalism; independence, not subjugation. Patrick Henry thundered that he “smelled a rat” in 1788 because he believed the Constitution violated the fundamental principles of the founding. But Anton absurdly proposes that Henry was “attacking a core pillar of the American founding” and therefore was somehow un-American.

Anton also suggests I am un-American for opposing his Claremont interpretation and the 1776 Commission report. If we conservatives want to be more credible than the left, however, it pays to present a real history of the American founding, warts included, and then we should explain the real reasons our founders should be admired.

The Founding Fathers’ promotion of liberty—not equality—and political independence, came out of a great Anglo-American tradition and served as the bedrock of American society. They were men of their times, and so it is wrong to hold them to the egalitarian standards of a later age, which is precisely what Anton does.

The American right would be better served by rejecting the ahistorical adulation of Lincoln and its fixation on the “All men are created equal” tropes in the Declaration. That would free us from the necessity of justifying the 1776 Commission report and return us to an American conservatism based on an accurate understanding of the American founding.

(Correction: Major-General Henry Lee was originally referred to as historian Henry Lee. This article has been updated to reflect his correct title.)

Image Credit:

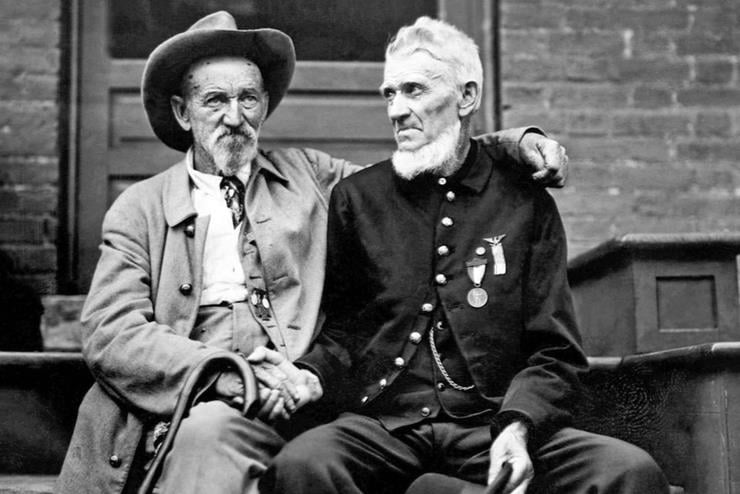

above: unidentified Union and Confederate veterans share memories at the 50th anniversary reunion of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1913 (Library of Congress)

Leave a Reply