Bruno Gentili passed away in Rome on January 8. He was Italy’s most distinguished scholar of ancient Greek language and literature. His contributions ranged from composing a popular textbook of Greek lyric poetry and the basic introduction to Greek meter for Italy’s classical high schools to editing scholarly editions of the texts of the Greek lyric poets. His important book Poetry and Its Public in Ancient Greece From Homer to the Fifth Century (1984; translation by Thomas Cole, 1988; new Italian edition, 1995) fundamentally changed the scholarly interpretation of Greek lyric poetry. Its style won it the Viareggio prize in Italy as a work of literature. Working with his friend, the literary critic Carlo Bo, Gentili helped make the small private university of Urbino a center for studying humanities. As emeritus professor, he continued to influence research at Urbino, produced a new and completely rethought and revised scholarly book on Greek meter and music and two volumes of the works of the poet Pindar, where his own compelling translation into Italian accompanied the research of his students.

Gentili was a polymath, writing on Greek and Latin, but he always returned to Greek lyric poetry. Modern classics arose in 19th-century Germany in the Romantic period. Lyric poets were viewed as pouring out their emotions to express their unique personality in passionate, spontaneous verse. Naturally, classicists interpreted Greek poems in the same way. They debated the character of the poets. Did Sappho express an unhealthy interest in young women? French writers thought so. No, thundered the great German philologist Wilamowitz Moellendorff. Sappho was no degenerate French woman, but a loving schoolteacher whose beautiful poems reflected the healthy pride of a great teacher for her students. When he delivered these views in a public lecture in Berlin, we are told, women in the audience wept with pride and joy to hear the honor of the world’s greatest poetess defended by the world’s greatest classicist.

Gentili changed all that. Greek lyric poetry was not the private emoting of a lonely writer, like Emily Dickinson in cold Amherst. It was performed publicly as the living expression of a profoundly “oral” society to worship the gods, celebrate athletic victories, and enliven drinking parties. A few great poets composed, but many people sang and danced in choruses or at symposia. Poetry was an integral part of a living, breathing, singing, and dancing culture. It seems so different now, although Friedrich Nietzsche noted in his first book that the spirit of community shaped by music was still alive in the hymn singing of Lutheran congregations. A few men compose the words and music, but the whole congregation sings. They “make a joyful noise unto the Lord in song.” They “come before his presence with singing.”

Gentili was a European presence in scholarship while teaching and studying in little Urbino. The most prestigious Italian universities are urban. Urbino is a small Renaissance town perched on a hill in the Apennines far from a major city. You get there by driving a car or riding a bus; there is no train station. In the second half of the 20th century Carlo Bo as rector and Gentili as president of the faculty kept private Urbino a center of humanities teaching and research. It is now state funded, but the traditions Gentili and Bo stood for still thrive there.

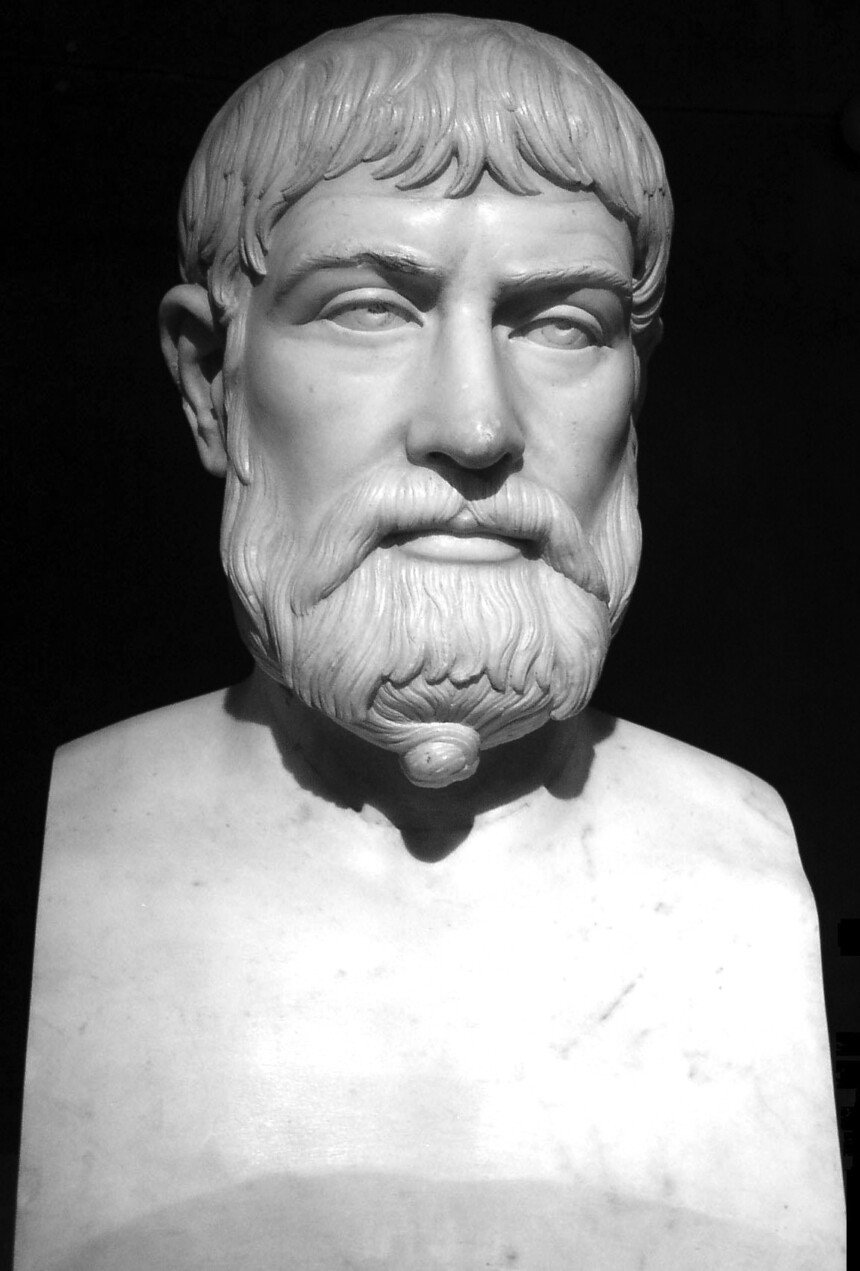

This past September Gentili’s edition of Pindar’s Olympian Odes was published in the distinguished Lorenzo Valla series. Gentili’s students equipped it with a thorough and up-to-date commentary to accompany his masterly translation. Pindar’s words and the structure of his verse, the form the words take on the page—the scholarly term is colometry—reflect the form found in medieval manuscripts, which report the work of scholars in the great library in Alexandria in the third century b.c., who edited and preserved the masterpieces of fifth-century literature—lyric, tragic, and comic, and the Homeric epics. Editors of Pindar arrange the poems on the basis of modern ideas of meter, just as scholars used to interpret the texts on the basis of modern ideas of literature. The interpretive battle has been won among scholars, but the metrical battle continues. Here as in so many other areas of our lives we are still under the hegemony of Enlightenment ideas and the 19th century’s development of and reaction to them.

In 1989 the international classics organization FIÉC (Féderation Internationale des Études Classiques) met in Pisa, Italy. The important French Hellenist (and superb stylist) Jean Irigoin organized a panel on textual issues that included a presentation by Drs. Thomas Fleming and E. Christian Kopff of the United States on the survival of ancient meter in the manuscripts of the lyrics of Greek tragedy. We distributed a one-page handout with a summary of our talk in French and Italian. No one seemed very interested, and during the discussion period that followed the talks, Irigoin suggested moving past our paper. A voice rang out from the back of the auditorium: “No! Ho un intervento che debbo fare sulla conferenza di Kopff!” (“I have a statement I must make about this lecture!”) Bruno Gentili descended to the front of the room to report that what we had noticed about the lyrics of Greek tragedy he had noticed about the lyrics of Pindar. If our observations were well founded, this was important.

“Vous voulez répondre, M. Kopff?” Irigoin inquired glumly. I nodded, stood up, and responded in Italian. That broke the dam. One of Gentili’s brightest students, Giovanni Comotti, stood up to explain that we were wrong because we were contradicting basic principles of the history of ancient texts developed over the past two centuries. The debate continued until officials had to turn the lights on and off to clear the auditorium. The most exciting discussion of the entire conference was not about sex, class, or political power, but about Greek meter. That evening Dr. Fleming and I celebrated by smoking two Cuban cigars I had purchased in Amsterdam a week before.

Every September a summer school on “Metrics and Rhythmics” meets in Urbino under the leadership of Gentili’s student Prof. Liana Lomiento. Students and faculty come from all over Europe (though not England) to study the ancient evidence for Greek meter and music, a small specialty of an old subject within the shrinking field of the humanities. They are learning the practice of tradition, how to recover what once was known and may still be important. Learning how to recover the words and the form of ancient texts can lead to learning how to recover the wisdom contained in those words and shaped by that form.

It is one thing to say that Gentili began by writing an introduction to Greek meter for Italian classical high school students and went on to change—or restore—the way we read Greek lyric poetry. There is no way to give an adequate idea of his living presence as scholar, humanist, and teacher. While sipping tea in his apartment before going out for dinner, he would speak in language that would range from elegant, even highfalutin, to vulgar and funny. “He was capable of tempests,” Professor Lomiento told the Italian press and added, “he was volcanic.”

I once tried to put in a good word for a friend who had been his student but had gone his own way. Gentili repeated his name scornfully. “Lo sputo della mia bocca.” (“I spew him from my mouth.”) Then he turned away to encourage a student in her work. I think of what Samuel Johnson said to Boswell about Edmund Burke: “[I]f you met him for the first time in the street where you were stopped by a drove of oxen, and you and he stepped aside to take shelter for five minutes, he’d talk to you in such a manner, that, when you parted, you would say, this is an extraordinary man.”

The young American architect in Helen MacInnes’s Decision at Delphi tells the skeptical Greek anarchist, “The past and the present aren’t so far removed. They are just separate rooms in the same house, and if you unlock the doors they all connect.” Bruno Gentili unlocked these doors for his colleagues, his students, and his country and showed us how we could move from room to room without getting lost. He had a scholar’s passion for accuracy and a humanist’s sense of style. His presence guides and encourages us still.

Image Credit: Bust of Pindar, Roman copy, fifth century B.C.

Leave a Reply