Why we don’t need grand theory.

Conservatives understandably want to see our current cultural and political crisis as an apocalyptic struggle rooted in grand philosophical issues of good, evil, and the nature of the universe. Public schools inviting half-naked groomers to twerk in front of small children seems a portent of something earth-shattering. The COVIDiocy, with its lockdowns, child gagging, and banishment of the elderly to disease infested nursing homes was (and may again be) the kind of tyranny that kills societies.

Unfortunately, when the stakes are the highest, attempts to place our current crisis in a grand theoretical context can do more harm than good. The enemies of our way of life have done us the service of making clear the depth and breadth of their hostility toward every aspect of our tradition. In a time of such primal conflict, too much attention to broad causes may produce two alternate but equally debilitating responses. First, unreasoned boasting of our tradition’s supposed perfections, turning politics into a kind of civil religion. And second, a kind of self-flagellation—or “America flagellation”—that mischaracterizes the tradition we are losing and leaves us pining for a lost world that never really was even as the barbarians, already within the gates, continue to rape and pillage.

Abandoning our tradition-based constitutional republic, whether for a mythical medieval shire, an idyll of Lockean abstractions, or even a Church militant, is neither necessary nor prudent. While our republic and our character as a people each may be lost in its full vigor, they remain the sole historical bases on which we may rebuild a decent, civil social order.

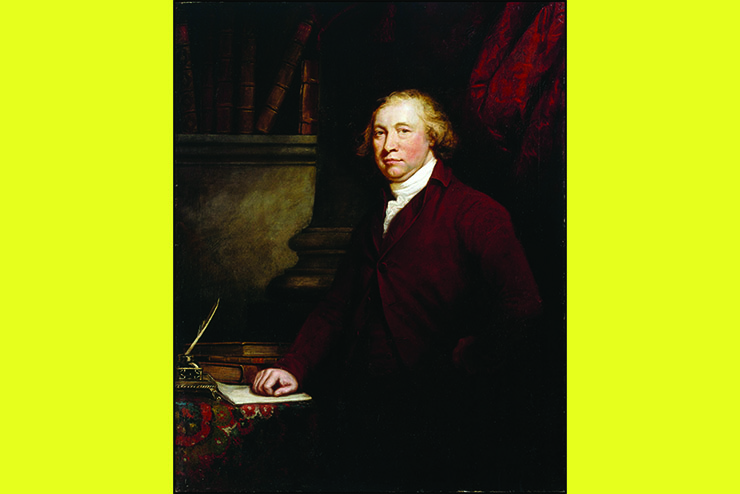

In this light, I’d like to offer some observations from the 18th century Anglo-Irish statesman, Edmund Burke. Burke is and should be a consensus figure for conservatives. He remains oft-quoted because he both gave measured support to American revolutionary claims in the face of British tyranny and, soon after, faced down the French Revolution that spawned our current madness. His positions were less a matter of grand theory than of pointing out each revolution’s practical consequences for human character, social cohesion, and the maintenance of civilized life. He can serve as a guide helping us develop a clear-eyed view of our adversaries’ character and goals, our own assets, and the grounds of contention, especially that for which we must fight.

To begin, we must understand with Burke that politics is fundamentally a matter of character. As he put it in his Reflections on the Revolution in France, “men of intemperate minds cannot be free, their passions forge their fetters.” Burke’s adversaries were the grandfathers of our adversaries. They were the “sophisters, economists, and calculators” empowered by French revolutionary rationalism; these Jacobins were men of small, twisted souls who sought unlimited power by tearing down France’s fundamentally religious social order and replacing it with grand schemes of mass organization and control. But compared to the “social justice warriors” of today they were veritable giants.

We no longer live in a time of great, murderous revolutions. We live in the wasteland created by Jacobins, Marxists, Maoists, and Progressives. The Jacobins claimed to be freeing people from the dead hand of the past so that their natural goodness could rule. In reality they stripped from the people what Burke called the wardrobe of a moral imagination—their self-understanding as social beings in need of faith, family, and the genuine freedoms of local self-government. The revolutionaries left only man’s naked, shivering nature, to be reshaped by those in power. Having done so, however, they left their successors with only broken characters and warped personalities, incapable of engaging in reasoned, good-faith discussions regarding the common good.

We must take the fact of our adversaries’ corrupt characters into account in our current struggles. For example, while it is easy to show the basic flaws and dishonesty undergirding today’s claims of “systemic racism,” “gender fluidity,” and various cooked-up global crises, the purveyors of these delusions cannot be argued out of their positions. Resentment, greed, psychological trauma, and pure lust for power, not reason, explain the actions of those on the front lines of the culture wars. In political terms, they are simply working to eliminate social and cultural obstacles to absolute political power.

Today’s social activists serve their inner demons and the interests of myopic functionaries in Washington. Indirectly, of course, they serve the high-tech and financial overlords whose money buys them power but not wisdom. In their often-delusional thinking, these would be global demigods and their servants are not working to solve any specific crisis, let alone establish any specific utopia. They simply want to keep power in “the right hands.” Thus, debates over “climate change” and the like are largely beside the point. There will always be another crisis so long as we cede to our central government any claim to legitimacy in ordering our lives as one formless, subject people.

Those possessing ruling class credentials and/or wealth care little whether most of us are impoverished, effectively enslaved, or even killed by various experiments and side-effects so long as we can be organized into more efficient units. Through control of public education, agriculture, transportation, and daily life (e.g., determining who will receive how much electricity once our overlords render it in short supply) our betters are working to get more product from us per calorie consumed. They will make us exist in ways far more symmetrical and aesthetically pleasing to them than the chaos of families, churches, and that plethora of local associations and functioning local governments that once characterized our common life.

A life sustained by eating bugs in our dormitories while waiting for the electric bus to take us to work in our cubicles might sound bad to you and me, but it would leave plenty of untrammeled environment for elites and their hangers-on to enjoy; it would look good on a spreadsheet; and it might just be sold to the common American as a great way to make sure there is plenty of tech and dope to go around.

Reasoned discourse will not stop this onslaught. Plutocrats have no motive to listen to reason, or even allow it to be uttered. They will not be won over and so must be neutralized by taking down their power structures in the deep state and its supporting institutions. There is, then, no substitute for radically shrinking the size and power of the political, social, and cultural institutions arrayed against decent self-government. To take back local school boards and local government more generally, to ban public sector unions, eliminate universities’ subsidies and their control over status, end civil service protections, disarm armed bureaucrats, and eliminate the FBI and other elements of the surveillance state, would be only to make a good start.

Electoral politics promise little. Around half of Americans (far higher percentages in Canada and Europe) have followed their appetites into addictions to drugs, social media, and/or ideologies that render them incapable of recognizing, let alone practicing, genuine ordered freedom. And we can expect few allies among our political class. Every branch of the federal, most state, and even local governments, along with nongovernmental pressure groups from public-sector and teachers’ unions, to corporations and charitable organizations, have been corrupted by persons and ideas deadly to good character. The deep state runs the federal government because legislators choose to make vague so-called laws declaring that various ills shall be cured and then hand the actual law-writing over to bureaucrats. Instead of taking the time and risk of writing detailed, purposeful legislation and thereby take responsibility for their actions, they punt. The goal is simply to stay in power, enjoying its lucrative benefits through influence peddling—separation of powers, federalism, and the rule of law be damned.

How do we come to some agreement with our adversaries on issues of the day? We don’t, because we can’t. What can we who value our traditions but control no center of power, do? What assets do we have to defend and rebuild our way of life?

Hope lies, somewhat ironically, in the historical American character—a character Burke professed to find somewhat distasteful. Burke urged Britons to govern us, not according to general ideas, but according to our character as a people, or let us go. That character was unruly. Americans, he said, “augur misgovernment at a distance; and snuff the approach of tyranny in every tainted breeze.” They have a “fierce spirit of liberty” developed from their British traditions, combined with dissenting religion, settler experience, and long-standing habits of defending their (sometimes overstated) rights as persons and communities. All this had spawned traditions hostile to centralized power and rooted in local self-government. And Americans were willing to fight for their way of life.

Americans were not merely unruly. Left to themselves they also were self-governing; their passions were “fettered” by traditions that emphasized limitations on political power and the duties of republican citizenship. Where the French Revolution led to mass murder, the American Revolution led quickly and smoothly to self-government. As Burke noted at the time, the Americans “formed a Government sufficient for its purposes, without the bustle of a Revolution, or the troublesome formality of an Election. Evident necessity, and tacit consent, have done the business in an instant.”

It is this character, still dominant in a significant portion of the country and people, and still latent or at least reachable for many more, on which we must build. Americans know this. The ill-fated Tea Party movement of 2009 sought to tap into this reservoir of unruly action, but was too polite and too vigorously put down by government actors before it had garnered enough supporters. The deep state has become even more vigilant and vindictive. But “the spirit of ’76,” while a bit cloyed as a slogan, remains active, as it has over the course of our history as our settler people forged new lives in their communities, often in opposition to national political forces.

We have examples to follow. But they are to be found less in the realm of politics than in that of local life, rooted in the most local concerns. I think in particular of those brave Armenian-American parents in Glendale who refused to be cowed by Antifa beta-thugs seeking to shut down opposition to child grooming in the public schools. They fought to protect their children from people they knew, in their bones, mean harm to their characters.

Other examples abound, not least the long-term activism that finally brought an end to the travesty of Roe v. Wade and began the real work of changing hearts and minds in our states regarding the sanctity of unborn life. On abortion, as with every important cultural issue, the fight has just begun; the dark money victory in Ohio’s recent elections, enshrining in the state constitution a “right” to kill children in the womb for any reason at essentially any time, is proof of that. Then again, overturning Roe achieved only one small but necessary good: stopping the national courts from imposing an abortion regime on every American. Resuscitating a civilized understanding of childbearing, as with cultural issues more generally, is the work of generations; it must be undertaken within each state and community, even as disinformation and activists are piped in and shipped in by globalists.

The key to any substantial victory is recognition of the real grounds of contention, namely control over our own lives as communities. Americans long demanded the freedom to publicly worship, educate their children, and maintain order for themselves within their townships. Here we see a third Burkean insight important for American recovery: the grounds of contention today come down to respect for our “little platoons.” This Burke quotation is perhaps too-well known, as it is too-little understood: “To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affections.” This is not some call for withdrawal into idyllic isolation or for a sentimentalist politics It is a call to recognize, encourage, and build upon the wealth of social, economic, and political ties naturally formed in local associations to protect our fundamental traditions—what we know is good in part because it is and long has been ours.

The American Way was real, rooted in families whose rights trumped the demands of the state because families are more natural and fundamental than the state. Churches were central because religion is natural to us and because they, like other local associations, are a traditional focus of community life. The government, to the extent it affected people, was primarily local and rooted in the needs and demands of its people to protect families and other associations from violence and outside forces. Broader, more distant powers were distinctly derivative and severely limited.

We must remember that it is right to question authority, especially centralized authority, and that civility is a good thing only among those who seek the common good. Too many of us have become too compliant in the name of “law and order” at a time when laws are few and orders coming from central powers are many and both illegal and unjust. The required government reforms are simple but far-reaching and must begin with simply dismantling current centers of power in Washington and especially its deep state.

This will come about, not by seeking common ground with an utterly corrupt set of adversaries and false friends, but by working through lawsuits, whatever electoral tools come to hand, and public action to encourage and build on local, natural associations devoted to protecting our children and our way of life.

Leave a Reply