Last year, just before his 21st birthday, my son Jacob learned of a condition called aphantasia. In its strictest form, aphantasia is the inability to create mental images. Like many such conditions, aphantasia affects those who have it to varying degrees. In Jacob’s case, his mental images are very fuzzy and indistinct. In my case, they are utterly nonexistent. When I close my eyes and try to conjure up an image, all I see—all I have ever seen—is blackness.

I was a few months shy of 50 years old when Jacob made his discovery. I had never heard of aphantasia, and my first reaction was disbelief—not that such a condition could exist, but that it wasn’t universal. From the time I became aware of language implying that we should be able to create mental images (at will or involuntarily), I had always assumed that such language was metaphorical. I had never thought that “Picture this” was meant—much less could have been meant—as a literal command.

The next several days were both disconcerting and exciting, as I experimented with family and friends and coworkers. I discovered that the ability to make mental images is not consistent—while almost everyone else, it seems, can conjure up a vivid image to some extent, there is a range of detail, as the difference between my experience and Jacob’s had already indicated. My daughter Cordelia has a very active and extraordinarily malleable ability to create mental images, and she quickly grew tired of my interrogations:

Me: Imagine a sheep. What color is it?

Cordelia: White.

Me: How many legs does it have?

Cordelia: Four.

Me: Are you sure it’s white? Isn’t it purple?

Cordelia, with a nervous

laugh: It is now.

Me: And doesn’t it have six legs?

Cordelia, exasperated: It

does NOW.

At 13 years old, Cordelia has just won two local prizes for her art—hardly, it seems to me, a coincidence. In a similar interrogation, her older sister Grace, now 18, saw an orange sheep with five legs standing on the dome of the Huntington County courthouse, once I told her it was there. Grace’s images, though, are more cartoonish, while Cordelia’s are vividly realistic, even when they cannot exist in reality.

Assuming you haven’t turned the page already—since, in all likelihood, you have no trouble visualizing images and you find my inability to do so an uninteresting defect—the point of this column is not to introduce you to aphantasia, much less to declare myself special for having this condition, and even less to excite your pity. Rather, it is to explore the implications of a question that the quondam Chronicles author David Mills raised when I discussed aphantasia on Facebook. In response to my self-diagnosis, David asked whether I thought my condition may have affected my politics, and how.

Because of the way in which David phrased a portion of his question (“For example, does this make you more rational/more principled/less swayed by emotion or [as a critic of your politics would say] less sympathetic/less caring?”), I responded a bit churlishly at the time, but I’ve thought a lot about his question over the intervening year, and I think that David may be on to something.

My political views, as well as my religious ones, have always been deeply connected to my epistemology—my understanding of how we know what we know. Epistemologically, I am an empiricist—not in the modern, limited sense that excludes any experience that is not reproducible and quantifiable, but in the Aristotelian sense: We have no knowledge of reality except through our experience. Even our leaps of intuition depend, at base, on prior experience.

By my early 20’s, as a grad student in political theory at The Catholic University of America and long before I learned of aphantasia, I had become a dedicated foe of philosophical abstraction—and the social and political consequences of the modern embrace of it. Reconstructing society on the basis of theories that have no basis in the lives of real people living in real places makes as much sense to me as worshiping an orange sheep with five legs perched on the dome of the Huntington County courthouse would. I have no use for economic “laws” based in “self-interest” that are contradicted by the everyday experience of family and community life. I recognize that men and women and even children routinely set aside their “self-interest” out of love for others, and that characterizing such actions as exceptions to the norm is, in fact, an attempt to redefine the norm.

The love of a mother for her child, family ties, the bonds that bind a community together—all of these are things that we can and do experience, but they are not quantifiable in ways that translate into economic laws or political systems. They are, however, all experiences that remind us, as Christians, of our encounter with the One Who created us, Who mourned our fall, and Who died to save us from ourselves.

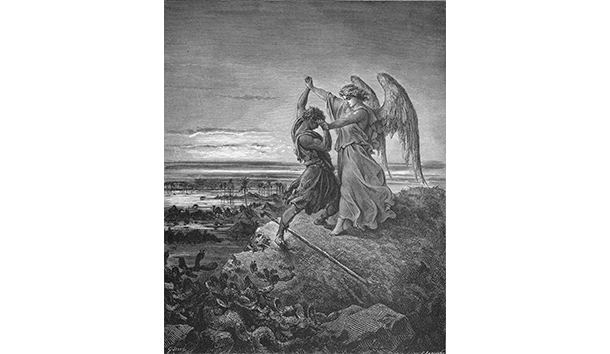

A god who does not become man must remain, in a very real sense, forever outside of human experience. Those who are not aphantasic may conjure him up, but they risk creating him in their own image. A God Who becomes man, however, is like the angel whom Jacob faced at the ford of the Jabbok: someone with whom one must wrestle—a reality, and not an abstraction. And wrestling with Him must inevitably affect how one views the rest of the world.

Leave a Reply