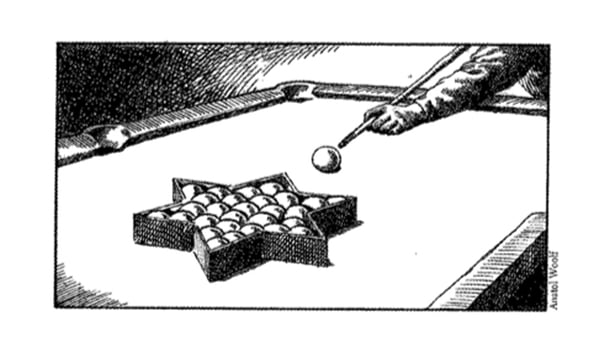

Any conversation about conspiracy theories inevitably turns to “the Jews.” On one hand, the critics of “international Zionism” claim that U.S. foreign policy (or the world’s resources) are being devoted to promoting Israel’s interests; on the other, there are those who warn against an “international Jewish conspiracy.” The second group can be traced at least as far back as the mid-19th century. Ranging from relatively reasonable social commentators to conspiratorial nuts, members of this group sometimes hallucinate about the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, an agglutinative text that owes much of its present form to the czarist secret police of the early 20th century. Making its way through France, Austria, and finally the United States, this steadily embellished narrative eventually entered the Middle East as an anti-Israeli document.

Behind the setting of the Protocols (in which Jewish dignitaries assemble in a Prague cemetery to discuss plans to take over the world) is a less bizarre belief Jews are clannish as well as resourceful, and this combination of traits may make them appear a unified force determined to conquer the gentile world. Despite exaggerations, psychologist Kevin MacDonald makes this argument in his books. MacDonald’s view of coordinated Jewish efforts does not require the existence of a Jewish state. It assumes a conscious, collective attempt by Jews in high places to acquire or expand power on behalf of their group—sometimes to the detriment of gentiles.

Until recently, however, Jewish infighting in the United States was far more intense than anything Jews suffered at the hands of WASP patricians. Dislike between German Jews and Ostjuden in New York could fill tomes of socio-psychological studies. A common Jewish explanation for why there was not more done to help Eastern European Jews escape the holocaust is that snooty German Jews in the United States blocked the entry of other, less socially acceptable Jews.

Moreover, there is no indication that Jewish liberals in the media or at universities behave differently from their pseudo-Christian counterparts. At one point, Yale and Princeton both had Jewish heads, while Harvard was led by a Catholic president with a Jewish father. Still, these university presidents were selected not because of concerted Jewish efforts but because the old WASP establishment looked favorably upon them, and because they may have exerted themselves a bit harder to climb up the greasy pole of professional success. There seems to be no central Jewish control responsible for the rise of Jewish liberal academics and mediacrats to eminence. And whatever obnoxious ideology Jewish liberals spread, others in the United States, Canada, and Europe would happily promote it in their absence.

Zionists, in contrast to other Jews, focus their attention on building and supporting a Jewish state—and on trying to convince Jews (other than themselves) to settle there. This movement arose in the late 19th century in Central and Eastern Europe. Despite some reservations among Eastern European rabbinic leaders and the expected opposition of assimilated German Jews in Germany and the United States, the Zionists embraced what turned out to be a winning cause. But Zionists did not invent Jewish nationalism; it was there all along, even if it took the Zionists to give that sentiment a political expression.

Since the creation of Israel in 1948, this political expression has been easy to recognize, both outside the Jewish homeland and within it. Represented in the United States by such advocates as the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), Zionist activists have sometimes aroused anger through their intimidating tactics. They have targeted politicians thought to be friendly to Arab interests and helped to defeat two Illinois members of Congress, Charles Percy and Paul Findley, for championing negotiations between the Israelis and the PLO. Even more shamelessly, AIPAC has exploited misplaced American Christian guilt over the holocaust when lobbying for U.S. military support for Israel. If the source had not been a right-wing journalist, many Jews on the left would have agreed with Pat Buchanan’s description of how the “branding iron of anti-Semitism” has been wielded.

But the best days for AIPAC and other American Zionist groups may be in the past. In recent years, Jewish liberals have attacked Zionist intransigence for denying the injustices committed against the Palestinians. Although the New Republic continues to follow old party lines. Moment, Tikkun, and other American Jewish magazines both favor the Israeli-Palestinian peace process and proclaim the justice of Palestinian demands for statehood. They argue—with some justification—that it is dishonest for Jewish liberals to champion other victims of Western imperialism while slighting Arab minorities expelled by Jewish settlers. These second thoughts have surfaced alongside efforts within Israel to rethink the Zionist origins of that country. Partly influenced by a growing recognition that Arabs were living in Israel when European Jews arrived, this reassessment reflects other considerations as well: Israelis would rather Israel be a normal nation-state inhabited by their own nationality than a Middle Eastern extension of world Jewry or a colony of Miami-Dade County.

While the idea of a worldwide Zionist conspiracy seems less and less believable, the older conspiratorial view about concerted Jewish malevolence may be making inroads again. This is traceable, perhaps, to the form that Jewish separatism is taking. While, as Peter Novick shows in The Holocaust in American Life, there is a continuing obsession among American (and, even more, European) Jews with the holocaust, the set of interests attached to that obsession continues to change. Well into the 1980’s, that preoccupation was connected to support for Israel and was used to make Christians feel responsible for the relatives of people they had supposedly victimized. Once intermarriage became common, holocaustomania also provided a pseudospiritual link between Jewish agnostics and their gentile spouses reaching out to a persecuted minority.

All of this, however, soon developed into something more unpalatable, namely, the recasting of the holocaust as the ultimate symbol of evil in the present cultural wars. It came to represent the omega point toward which our “prejudiced” heritage would lead us unless politically correct managers and educators pointed us in the opposite direction. The national press and Jewish organizations argue that we are headed down the slippery slope toward the Third Reich unless we relentlessly crusade against homophobia, sexism, and Christian intolerance. The most shocking expression of it I have encountered was a recent display at the local Barnes and Noble, sponsored by B’nai B’rith and the National Gay and Lesbian Alliance. Next to The Diary of Anne Frank and other holocaust-related literature were Heather Has Two Mommies and further instructional studies produced by the advocates of “alternative lifestyles.” This reading matter, explained the accompanying poster, was essential to the crusade “to end hate right now.”

In fact, the holocaust’s association with fashionable agendas has become so clear that even critics of this arrangement try not to notice, if only for digestive reasons. When Congressman Jerry Nadler of New York perceives the “whiff of fascism” among George W. Bush’s supporters in Florida, when Alan Dershowitz tells us that homosexuals—like Jews —were exterminated under Hitler (as opposed to Poles, who were only “selectively murdered”), or when an elderly Jewish woman in Dade County compares the (presumably Republican) poll officials who put her in line to vote to the guards at Auschwitz, I try (usually to no avail) to ignore these predictable idiocies. Needless to say, gulags do not serve the same propagandistic function as Nazi death camps—that is, as metaphors for political incorrectness carried to an extreme. In France and Italy, under communist leadership, the political left has denied the historicity of communist atrocities, while backing the efforts of Jewish organizations to showcase the holocaust.

This highlighting of “fascist crimes” is tied to the punishment of “crimes of opinion” committed by presumed holocaust deniers and journalists who challenge multicultural immigration policies. Holocaust entrepreneurs have joined communist deputies to impose a steady diet of la politique commémorative upon the French people—official plaques and civic holidays that memorialize the deportation of Jews from France (most of them refugees from other countries) by the Vichy government. As noted by Eric Conan and Henri Rousso—two impeccably leftist French journalists who, nonetheless, fear that things may be getting out of hand—the fêtes nationales set up to commemorate the liberation of France from the Nazis have less and less to do with national heroism or national suffering and have become guilt trips laid on the French for what the Vichy government did —not as the government of an occupied country but as the representative of Catholic European society. Small wonder that the nationalist right in France risks criminal prosecution to complain about Jewish communist efforts to dishonor la patrie. While such callous acts did occur, the attempt to blame all non-leftist Frenchmen is both boorish and dishonest.

The alacrity shown by Jewish organizations that use the holocaust to promote political correctness and multiculturalism is not, as far as I can see, aimed at dominating gentile society. All Jewish liberals I have known believe that the United States and other Western countries are swarming with hostile Christians and that the Religious Right is as dangerous as the Nazi movement before Hitler came to power. Although I am not often on their side, I fully share the amazement of Norman Podhoretz and Elliott Abrams, who, after looking at the attitudes of American Jews regarding the prevalence of antisemitism in the country, wondered aloud whether they shared the same reality.

The Religious Right, a screed put out by the Anti-Defamation League in 1994, illustrates this mindset. Abe Foxman and the rest of his equally anxious executive committee think that the Religious Right’s “assault on tolerance and pluralism” signals a widespread antisemitic and homophobic Christian culture. Pious Americans who favor prayers in public schools or creches in public places or who try to place restrictions on abortion are not fellow Americans with whom the left has honest differences. These zealots are the forerunners of antisemitic theocracy and exemplify (note the originality of this characterization) the “paranoid style in American politics.” One telltale proof of this style is the tactlessness of Christian “extremists” who compare abortion to Nazi inhumanities. Unlike gays, blacks, French Stalinists, and impatient geriatric Jewish liberal voters in southern Florida, opponents of abortion have no right to overuse holocaust analogies.

Leave a Reply