Pat Buchanan set off political sparks during the 1992 primaries with his charge that President Bush was allowing foreign agents to run his reelection campaign. Ross Perot later fanned the sparks into a prairie fire with accusations that former government officials earn $25,000 and $30,000 a month representing foreign interests. Bill Clinton joined in with a campaign blast at “high-priced lobbyists and Washington influence peddlers.”

Rarely had this inside-the-beltway issue drawn such a stir in a presidential campaign. But it did not take long for the flames of revulsion to flicker and fade. The main targets of criticism, Charles Black and James Lake, remained as officials in Bush’s campaign. Clinton’s staff also included Americans who had lobbied for foreign interests, and he named a few to high positions in his administration even while issuing orders to tighten control over foreign lobbying.

In reality, no President or Congress has been able to avoid working with lobbyists if only because of their knowledge of government and their ability to get things done in Washington. Indeed, lobbying is an entirely legitimate form of free speech in a democracy. “The real issue,” says Pat Choate in his book Agents of Influence, “is whether the manipulation of America’s political and economic system by . . . foreign interests has reached the point that it threatens our national sovereignty and our future.” He might have added world peace.

Many of those who represent foreign firms and governments make an effort to comply with the Foreign Agents Registration Act requiring disclosure of certain information. But the law is weak and “ignored every day of the week,” according to Jack O’Dwyer, publisher of a newsletter on foreign lobbying. As a result, it is impossible for anyone to get a clear picture of the impact of such influence on American government and public opinion.

Not all foreign representatives pose the threat cited by Choate. Most are concerned only with such matters as seeking financial aid and improving a country’s trade or public image in the United States. But others go far beyond this point, working largely in secret to alter public opinion and government policy on matters as vital as war and peace. Take the Persian Gulf crisis, for example. In the five months between Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait and the first bombing runs, few Americans were aware of all the foreign interests in Washington trying to get American troops into battle without waiting to see if trade sanctions would work. One of the most influential forces was Hill & Knowlton, the nation’s largest public relations firm. Another was a mysterious organization dedicated to promoting Israeli interests known as the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC). Though neither calls itself a foreign lobby, both use large sums of money to influence public officials on behalf of other countries, the essence of foreign lobbying. And they both have enjoyed considerable success, largely beyond sight of the news media. In fact, it was not until long after the Persian Gulf War began that some of the secret manipulations leading up to it Isecame visible.

In the case of Hill & Knowlton, the p.r. campaign it conducted for the Kuwaitis—in the name of a front group called “Citizens for a Free Kuwait”—turned out to be one of the most effective ever. It was also one of the most lucrative, yielding over $11 million for only 20 weeks of work ending when the war started in January 1991. But to the Kuwaitis, the price represented only one ten-thousandth of their royal family’s holdings outside Kuwait during the war, surely a bargain for getting their oil patch back.

In seeking to get the United States into war, the firm left no lever of influence untouched. It even had a man at the White House, an old pal and former staff chief of Mr. Bush, Craig Fuller. While serving as the firm’s president and chief operating officer, he was frequently observed by reporters at the White House during the Gulf crisis. Precisely what he accomplished is not known. But at least one unusual event had his fingerprints all over it.

It was a special meeting of the United Nations Security Council just two days before its vote to set January 15, 1991, as the deadline for Iraq to pull out of Kuwait. When U.N. members arrived on the morning of November 27 expecting to debate a Palestinian issue, they found their august chambers turned into a propaganda forum for Kuwaitis with gory stories to tell about Iraq’s occupation of their tiny fiefdom. The walls were plastered with photographs of alleged torture victims, and an extra large contingent of journalists had been invited by H&K to see the horror show. When some American members objected, they were overruled by United States Ambassador Thomas Pickering, whose turn it was to serve as president of the council that day.

During morning and afternoon sessions, Kuwaitis testified to many unspeakable atrocities reportedly committed by the Iraqis. The most shocking story was told by a man calling himself a surgeon and claiming that 120 newborn babies had been dumped out of their incubators and left to die on the floor. He said he had helped bury 40 of them. News outlets gobbled up his allegations without question or even a hint to the public about the p.r. machinations so clearly apparent to reporters.

Actually, the incubator charges were not new; only the numbers were. Six weeks earlier, a 15-year-old Kuwaiti girl identified only as Nariyah, a hospital worker, had caused a sensation when she tearfully told a public hearing of the Congressional Human Rights Caucus that she had witnessed 15 such murders by Iraqi soldiers. Eventually, Amnesty International pushed the toll to an incredible 312 in testimony before the House Foreign Relations Committee. That was far more than even the number of incubators in Kuwait.

H&K had done its job well in arranging these public forums, rounding up witnesses, and writing testimony. The escalating incubator charges had a strong impact on the American people and their elected representatives. Several legislators cited them among the reasons they voted for military action. President Bush trumpeted the claims on numerous occasions. John R. MacArthur, author of a book on the Gulf crisis, called the charges “the most influential factor” in getting the United States into war.

But the story was not true. The facts did not emerge until after the war when reporters went to Kuwait to check on the accusations. They found abundant evidence of Iraqi cruelty but nothing to indicate that infants were deliberately murdered. A year after hostilities had ended, MacArthur revealed that the alleged hospital worker was actually the daughter of the Kuwaiti ambassador to the United States. Private investigators working for the Kuwaiti government later interviewed her and found that she had been merely a brief visitor to the hospital and had seen only one baby outside its incubator. Meanwhile, the U.N. “surgeon” turned out to be a dentist professing no knowledge of incubator deaths.

But it was too late to matter to anyone except I I&K’s competitors in the public relations business, who resented the possible effect of the firm’s behavior on the image industry’s public image. Yet this was not the only debatable activity of the firm in the name of Kuwaiti “Citizens.” Behind that facade, the firm generated much propaganda for war by organizing rallies and special “days,” such as National Free Kuwait Day. It also produced and distributed 40 video “news” releases, recycling creations like Nayirah’s story as news to viewers around the world.

Unlike some American representatives of foreign interests, H&K eventually registered at the Justice Department as a foreign agent, disclosing details of its contract but no copies of its propaganda as required. It was not until April 1992 that “Citizens” finally filed data revealing its true identity as a creature of the Kuwaiti government, not a grass-roots organization as indicated by its title.

Meanwhile, agents for Kuwait set up other “citizens groups,” which advertised widely for military action. One was The Coalition for America at Risk headed by Sam Zakhem, former U.S. Ambassador to Bahrain in the Reagan administration. In a full-page ad in the Washington Post, the group warned against negotiating with Saddam Hussein. In a news story, the Post trustingly reported that the group had raised nearly $1 million from private citizens. Eighteen months later, the paper reported Zakhem’s indictment on charges that he had secretly taken $7.7 million from Kuwait’s ambassador for a grass-roots campaign but had diverted all but $2 million to himself and two friends.

Another effort to win public support for war was launched by the Committee for Peace and Security in the Gulf. It started with a full-page ad in the New York Times arguing that more urgent than freeing Kuwait was destroying Iraq so it could not “threaten the security and well-being of all nations.” Co-directors were Richard Perle, a defense official for Reagan, and Ann Lewis, a former political director of the Democratic National Committee. The main organizer was Stephen Solarz, a New York congressman who was gerrymandered out of office in 1992.

What was not said in the ad was that the organization represented the unspoken but influential Israeli factor in the Gulf affair. The 50 prominent signers of the ad reflected the unique power of the pro-Israel lobby to unite liberals and conservatives, Jews and Gentiles, in bending American foreign policy to the benefit of the Jewish state. Solarz, a liberal Democrat, was one of the leading backers of Israel—and war—on Capitol Hill. The Committee had enough clout to meet with President Bush twice. The ad reflected the expressed fear of Israeli government officials and others that the budding U.N. coalition might free Kuwait but not destroy Iraq’s military power, which they saw as the principal threat to Israel’s security.

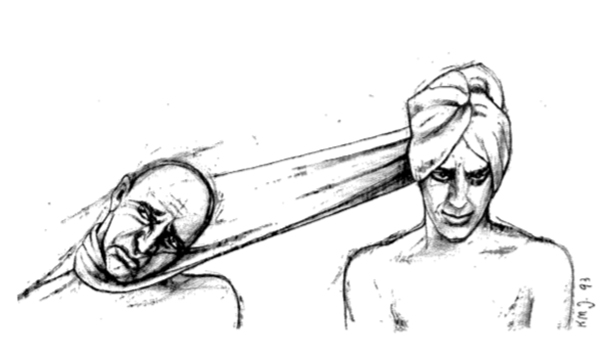

Although the Israeli factor in the Gulf crisis was “very instrumental” according to James Zogby, president of the Arab American Institute, it was rarely discussed in public. Three weeks after the Iraqi invasion, right-wing commentator Pat Buchanan blurted out on a TV talk show: “There are only two groups that are beating the drums for war in the Middle East: the Israeli defense ministry and its amen corner in the United States.” Although his remark contained some kernels of truth, he had broken an unwritten rule of American politics: never criticize the Israeli lobby in public. The usual penalty for a non-Jew who utters such remarks is to be forever labeled an anti-Semite. The chief enforcer in this ease was New York Times columnist A.M. Rosenthal. With unrestrained anger, he accused Buchanan of spreading “venom about Jews” and implying that Jews have “alien loyalties for which they will sacrifice the lives of Americans.” These charges shadowed Buchanan throughout his campaign for President.

Not until after the war had started did the sensitive topic attain the status of news. That came in a Wall Street Journal story telling how the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) had “worked in tandem with the Bush administration” in a “behind-the-scenes campaign to gain authority for the President to commit American troops to combat.” Reporter David Rogers said AIPAC’s influence was “crucial” to that decision, though the group “took pains to disguise its role.” Executive Director Tom Dine acknowledged that AIPAC had been active.

Indeed, quiet power is the trademark of AIPAC, the biggest pro-Israel lobby group in the United States, with a staff of over 100 and a budget of $14 million from American donors. It is also “the most powerful, best-run, and most effective” foreign lobby in the United States, according to the New York limes. Founded in 1959 by Zionists, AIPAC has become the dominant political voice of American Jews. In recent years, it has sought to strengthen its leadership by establishing a secret investigative unit that author Robert I. Friedman says is used to harass dovish Jewish groups and what it calls “anti-Israel activists.” AIPAC officials deny the accusations.

Much of AIPAC’s power comes from its ability to issue “action alerts” to Jewish leaders and to generate grass-roots action among many of the six million Jewish Americans. But its real power stems from its close ties with numerous pro-Israel political action committees (PACs) around the country and their ability to reward friendly candidates as well as punish those who stray from the demanding line that prevails among them.

AIPAC has consistently denied that it is a PAC or coordinates any PACs. But a memo and taped telephone call that have leaked from its inner sanctum have indicated to unbelievers that AIPAC has been very influential in determining where all the Israeli lobby’s money goes. Its activities include sending newsletters to its 55,000 members and holding frequent conferences and pilgrimages to Congress. The presidents of 48 major Jewish organizations sit on its board.

Citing this information, several former State Department officials and others filed a formal complaint in 1989 to the Federal Election Commission alleging that AIPAC was violating election laws by directing money to federal candidates through numerous PACs, thus avoiding legal limits on donations from a single PAC. Last June, FEC General Counsel Lawrence Noble decided that AIPAC had “probably” violated the law. But the commission vetoed his call for legal action.

The decision left pro-Israel PACs free to continue contributing the maximum allowance to each candidate. To help disguise the extent of their network, almost all these PACs omit the word Israel from their titles. The result is a patchwork of names like National PAC, Washington PAC, and Americans for Good Government. In 1984, author Ed Roeder managed to break the codes and make it possible to determine total amounts for the AIPAC lobby. According to Stealth PACs, a book produced by the American Educational Trust, pro-Israel PACs have consistently raised more money and contributed more to Congress than any other group. Yet reporters often omit the Israeli lobby from news stories about the largest PACs.

In 1987-88, for example, pro-Israel PACs raised $10.8 million and contributed $5.4 million to political candidates, according to AFT. The next largest spender was the National Association of Realtors, with contributions of $3 million. In the 1989-90 season, 95 pro-Israel PACs contributed $5 million, compared to $3.1 million from the realtors, the next largest group. Preliminary figures for the latest presidential campaign cycle are similar. Over the last five election cycles, pro-Israel PACs have raised over $50 million and spent nearly $24 million.

But that’s only half the story. Many of the contributors to these PACs give equal amounts directly to their chosen candidates. In a study of the 1990 campaign, the Center for Responsive Politics found that for every ten dollars that went through pro-Israel PACs, nine went directly to the same candidates from the same donors. On that basis, the total from pro-Israel contributors during this same period was closer to $46 million, more than three times what any other specialinterest PAC gave and 300 times what Arab-American PACs spent.

Such massive contributions have brought the Israeli lobby unchallenged control over Congress and American policy in the Middle East. Since 1979 its ardent backers have obtained $53 billion in direct and indirect assistance for Israel, far more than any other country has gotten, not including $10 billion in loan guarantees approved last year. Israel has also cost the United States another $300 billion or so for such things as lost arms sales when Arab nations had to seek other than American suppliers, according to George W. Ball, former Undersecretary of State and coauthor of Passionate Attachment.

Aid to Israel, unlike aid to other countries, is not subject to any American oversight or penalties for not spending it on intended purposes. Also unlike some other nations, Israel has never been denied aid because of its record on human rights or nuclear proliferation.

To make sure that Israel gets everything it wants, pro-Israel PACs have buried members of key committees with cash. Seven members, a majority, of the 1992 Senate Foreign Operations Subcommittee, which handled foreign aid, had divided $1.6 million from such groups over the past three elections, according to FEC data. An equal amount was paid by Israel directly to American lobbyists, according to the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit think-tank in Washington, D.C. But more important than the amount of aid to Israel has been the impact of these PACs on Middle Eastern peace prospects. Pro-Israel money has gotten Congress (mostly the Senate) to oppose almost every White House initiative aimed at stopping settlements on Arab land and negotiating peace with the Palestinians. Yet these issues are “central” to resolving tensions throughout the Middle East, according to George Ball.

The record begins in 1962, when Jewish groups proved too formidable for President Kennedy’s efforts to allow displaced Arabs to return to Israel. A similar initiative by the Nixon administration was scuttled when AIPAC sent 1,400 Jewish leaders to pressure key members of Congress against the idea. Lobbyists became particularly adept at using congressional letters and resolutions for their purposes, often with little notice in the press. In 1975, AIPAC got 73 senators to block a move by President Gerald Ford merely to consider a peace bid by Egyptian leader Anwar Sadat. Then in 1985, AIPAC got 72 senators to back a resolution that killed an effort by King Hussein and PI.O Chairman Yasser Arafat to start negotiations.

President Bush also got thoroughly burned for his efforts to seek a freeze on Israeli settlements in occupied territories, an idea overwhelmingly supported by American citizens. In 1989, when Secretary of State James Baker began pressing Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir on that point and others, 94 senators signed a letter telling Baker to back off. Later that year, 68 senators sent a letter urging Baker not to issue a visa allowing Arafat, who had made some conciliatory gestures, to address the United Nations in New York City. In October 1991, 70 senators sponsored a veto-proof bill to grant Israel’s bid for $10 billion in loan guarantees. But they delayed final action to give Bush and Baker time to bargain with Israel for a freeze on Jewish settlements in the occupied territories. Six months later, facing a tough reelection fight. Bush caved in, and the measure passed the Senate (99 to 0) and later the House without a housing ban. Altogether, Bush and Baker encountered more than a dozen such roadblocks on their way to setting up Mideast peace talks.

Failure of a legislator to support any measure desired by AIPAC often causes pro-Israel groups to funnel money with a vengeance to his election opponent. One of the few who has spoken out about this is ex-Senator James Abourezk, a Lebanese-American from South Dakota, who quit in despair over what he saw as hypocrisy in his liberal colleagues. “Senators who criticize Israel,” he said, “do so at their political peril. The lobby hurls the charge of anti-Semitism against those who dare to voice opposition to Israel’s occupation of contested territories, to the bombing of Arab refugee camps, and to other ghastly practices which, when undertaken by any other country, bring great cries of protest from the same people who will not allow criticism of Israel.”

In a noted case, Republican Senator Charles Percy lost a pivotal reelection bid in 1984 after being singled out for defeat by the lobby because of his vote for President Reagan’s plan to sell AWAC planes to Saudi Arabia and his expression of concern for Palestinian “rights.” Pro-Israel PACs gave $500 to him and $301,000 to Paul Simon, his Democratic opponent in Illinois. In addition, Michael Goland, a California businessman, spent $1.2 million directly on negative advertising against Percy. Goland was later fined $5,000 for concealing his identity. His expenditures were examples of “soft money,” which can legally be spent directly on a candidate’s expenses. Altogether, over $3 million went to Simon from pro-Israel groups, according to Edward Tivnan, author of The Lobby: Jewish Political Power and American Foreign Policy. Afterward, says Tivnan, AIPAC Director Thomas Dine claimed credit for the onslaught and said American politicians “got the message.” It was enough to frighten Congress into almost complete submission to the lobby ever since.

By concentrating funds on key congressional races, the network of pro-Israel PACs often exercises its biggest influence at the local level. The largest amounts are reserved for legislators with the best pro-Israel records and for challengers of legislators deemed to have imperfect records. Like Percy, most of the targets for defeat have been Republicans generally friendly to Israel. Victims include ex-Representative Paul N. McCloskey of California; ex-Senator Roger Jepsen of Iowa; ex- Representative Paul Findley of Illinois; and ex-Senator James Abdnor, an Arab-American from South Dakota. Survivors include Senator Jesse Helms, who barely escaped losing reelection to a PAC attack in North Carolina in 1990. Another near-victim is Senator John Chafee of Rhode Island, whose staff attributed his reelection in 1988 to exposure of the AIPAC campaign against him on 60 Minutes. Chafee did not get a cent from pro-Israel PACs, while his opponent, Richard Licht, received $242,000. That is 25 times the legal contribution limit for a single PAC. An earlier victim was former Democratic Senator William Fulbright of Arkansas. His crime was to hold public hearings on foreign lobbying.

As the 1992 election neared, the Israeli lobby had gotten virtually everything it wanted from George Bush, including pulverization of Iraq’s military power, stalled peace talks, $10 billion over five years in loan guarantees, $3 billion in foreign aid, plus, in the words of AIPAC President David Steiner, “a billion dollars in other goodies that people don’t even know about.” But lobby leaders were not satisfied. They steered their biggest contributors and most of their votes to Clinton and Gore, from whom they expected still more. In selecting Gore as his running mate, Clinton chose one of the most enthusiastic Israel-boosters in the Senate. In his campaign remarks, Clinton joined the choir. One-upping Bush, he said Israel should not be pressured to stop settling Arab land, adding that “the Arabs are the obstacles to peace.” Not all Jewish groups have agreed with hardline AIPAC stances. Some have sought to encourage talks with the PLO and an end to settlements on occupied land. But AIPAC has managed to build a virtual monopoly, much to the dismay of less conservative Jews and sometimes even to the displeasure of Israeli government leaders. Last August, the Washington Post reported that Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin accused AIPAC of inflaming relations between Israel and the United States by overplaying its hand on the $10 billion loan.

But his pique had no visible effect. By then, AIPAC leaders had deeply infiltrated the front-running Clinton camp. One even took to boasting about it. A month before the election, AIPAC’s Steiner told a potential contributor: “We have a dozen people in [Clinton] headquarters . . . and they’re all going to get big jobs.” He said he was already negotiating for the next Secretary of State. But when a tape of this conversation was given to the Washington Times, Steiner’s AIPAC presence suddenly evaporated. So did a few of the high appointments expected from Clinton. But Jewish leaders were unfazed. They took their complaints to the press.

That restored their clout in a hurry. Within hours of being named Secretary of State, Warren Christopher felt the need to call Jewish leaders and ask them not to worry even though he was not their preferred candidate. Clinton himself admitted he had “a problem,” which he promised to resolve with sub-Cabinet appointments. The New York Times quoted transition aides as contending that “the real worry of the Jewish groups” was that “their monopoly on representing Jewish positions is being broken.”

If “monopoly” means the absence of any countervailing place for Arab interests in American politics, the word is fitting. Despite signs that an Arab-American lobby is finally coming alive, it is hampered by limited funds and a relatively small population base in the United States. It is also hampered by a press with little interest in exploring all sides of the issues.

As a new administration took over in Washington, there were signs that Israel was shifting its position slightly. The Knesset voted to stop prosecuting citizens who contact the PLO. But, more importantly, there has been no change in policy or staff at AIPAC. The big questions for peace prospects in the Middle East remain whether AIPAC will relax its grip on American foreign policy and whether the Clinton White House will force the issue. The omens were not positive.

As Secretary Christopher sought to resolve an impasse between the U.N. and Israel over its deportation of some 400 suspected Arab terrorists, AIPAC got 68 senators to sign a letter backing Israel. The effect was immediate. Christopher approved a partial return of Arabs and agreed to veto any U.N. sanctions against Israel, at the risk of losing leverage with Arab parties in the stalled peace talks.

Nor were the omens positive that renewed efforts to reform election and lobby laws would dilute the power of such groups as AIPAC and Hill & Knowlton to shape American foreign policy in semisecrecy. The most likely plan to improve campaign laws would have little or no effect on pro-Israel PACs. And the leading proposal in Congress to tighten control of lobbying would not alter AIPAC’s status as a registered domestic lobby or diminish H&K’s role as a foreign agent for hire.

Coincidentally, the chief sponsor of lobbying reforms is Senator Carl Levin, a Michigan Democrat who received more pro-Israel money than any other member of Congress in the 1990 elections.

Leave a Reply