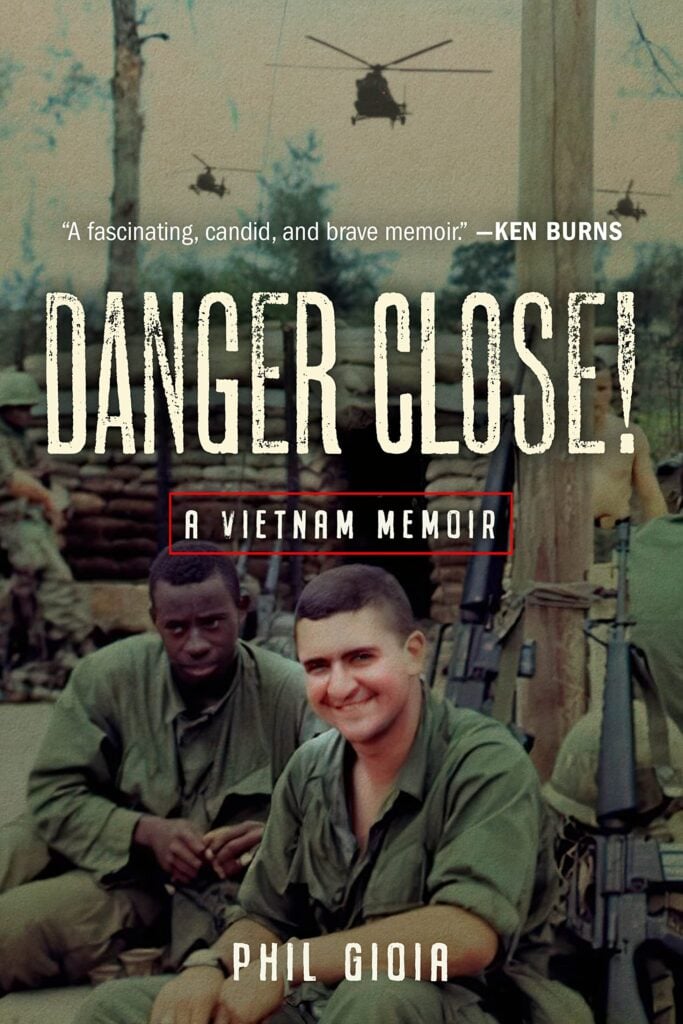

Danger Close! A Vietnam Memoir, by Phil Gioia(Stackpole Books; 335 pp., $29.95). This volume could have been titled The Life and Times of Phil Gioia because it’s not only his personal story of growing up in post-WWII America, but a history of the era. Gioia was a typical American boy, although as the son of a career Army officer, the family moved whenever his father changed duty stations, including posting overseas. Following Gioia through his early life is part nostalgia and part melancholy journey. The differences between then and now are profound. Sadly, most are not for the better.

Gioia was born in 1946 in New York City. His parents were children of Italian immigrants. At the time, his father, a WWII veteran who served as an intelligence agent in Italy, was stationed at Fort Dix in New Jersey. The family soon moved into base housing and Gioia’s life as a service brat began. In 1949 it was off to Yokohama. Gioia vividly describes his three years there and provides historical context for everything he experienced. This style suffuses the entire book—vivid personal recollections accompanied by a history of the place and era. The result is an engaging read and a history lesson.

When his father was stationed at West Point in the mid-1950s, Gioia became a Cub Scout and later a Boy Scout. He learned to shoot, hunt, and ride horses, and each summer was sent off to camp. He loved sports and competed with a vengeance. He also became a voracious reader, especially of military history and American heroes. This all was a boy’s life in the ’50s.

Gioia went to the Virginia Military Institute for college, which was something like spending four years in Marine Corps boot camp. He then subjected himself to the most demanding training the Army offered for infantry officers, including the famed Ranger School.

Gioia was as prepared as one could be for the war in Vietnam, which for him meant fighting mostly in the Central Highlands against well-equipped and well-trained North Vietnamese Army regulars, who could quickly retreat across the border into sanctuaries in Cambodia. He was first a platoon leader and then a company commander. Unlike some who secured rear-echelon duty, got their ticket punched, and returned home none the worse for wear, he humped hills, dodged bullets and shrapnel, and suffered from wounds and malarial fever.

Gioia takes the reader along with him in the heat, the muck, the stench, and the death. Nothing escapes his keen eye, and he pulls no punches.

(Roger D. McGrath)

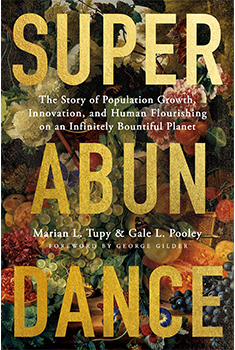

Superabundance: The Story of Population Growth, Innovation, and Human Flourishing on an Infinitely Bountiful Planet, by Marian L. Tupy and Gale L. Pooley (Cato Institute; 392 pp., $34.94). The Malthusian “settled science” holds that population growth will deplete Earth’s resources and doom us to starvation. Nobody pushed this theory harder than Paul Ehrlich in his 1968 book The Population Bomb. Today’s environmentalists are neo-Mathusians who continue to agitate for governments to curb population growth. China forced abortions as part of its one-child policy. In the 1970s, Indian authorities withheld water and wages from those who refused to undergo forced sterilization.

The authors of Superabundance demonstrate that Earth is not running out of food and resources for an increasing population. Just the opposite. Tupy and Pooley cite data showing for every percentage point of increase in population, food and resources increase even more. Why? Because the human brain is a powerful resource. More people on the planet means more innovation, which increases food supplies and material abundance.

Tupy and Pooley follow in the footsteps of polymath Julian Simon, whose book The Ultimate Resource 2 rebutted Ehrlich’s arguments. In 1980, Simon bet Ehrlich that five crucial commodities would not only be more abundant but cost less by 1990. Simon collected on the wager.

Superabundance arises when human creativity operates in an environment of free economic activity, scientific inquiry, and information exchange. Natural scarcity begets creativity. Take electric wires for example. As copper supplies dwindled, scientists transformed the abundant sand beneath our feet into fiber optic cable.

Tupy and Pooley introduce a new measurement: time price. Unlike currency, which governments can and do inflate, no one can create more time. The authors use this metric to compare the labor hours it takes in a given year to earn enough to buy something. Unsurprisingly, the required labor hours decrease over time due to human innovation. A 43-inch flat screen TV that cost $15,000 in 1997 has fallen an astounding 99 percent to $130 today.

The authors conclude that knowledge is the ultimate accumulated resource, based on the human capacity to learn. The human race is on a learning curve for creating abundance.

(Michael McCarthy)

Leave a Reply