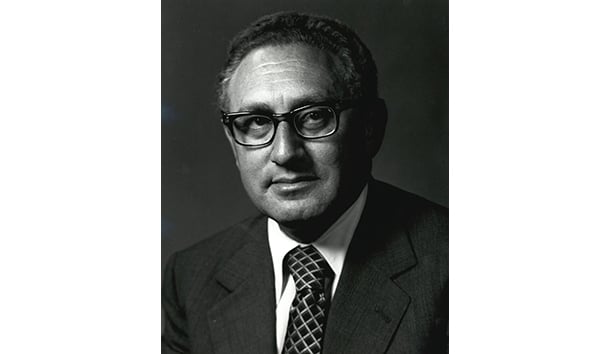

In his 1968 essay “Bureaucracy and Policy Making,” Dr. Henry Kissinger argued that there was no rationality or consistency in American foreign policymaking. “[A]s the bureaucracy becomes large and complex,” he wrote, “more time is devoted to running its internal management than in divining the purpose which it is supposed to serve.” There is only so much that even the President can do against the wishes of the bureaucracy, Kissinger warned. Unless he can get the willing support of his subordinates, simply giving an order does not get very far.

Three years later, Sen. Stuart Symington (D-Mo.) made a speech denouncing “the concentration of foreign policy decisionmaking power in the White House” which had deprived Secretary of State William P. Rogers of his authority. Symington singled out for attack “the unique and unprecedentedly authoritative role of Presidential Adviser Henry Kissinger,” who had become “clearly the most powerful man in the Nixon Administration next to the President himself.”

Symington’s diagnosis was correct even though his complaint was flawed. Nixon, an accomplished geostrategist, brought Kissinger on board and gave him extensive powers exactly in order to bypass the bureaucratic behemoth. It was an inspired move that allowed Nixon to open relations with China, crowned by his 1972 visit. It pushed the bipolar world in the direction of tripolarity and thus contributed to the weakening of the Soviet Bloc. Had Nixon relied on Foggy Bottom to see the project through, it may not have happened at all.

Half a century later, national security and foreign policy are still largely within the president’s constitutional purview, but the kind of control Nixon achieved appears unattainable in practice. President Donald Trump has faced formidable obstacles, both from his top appointees and from within the bureaucratic apparatus.

Former National Security Advisor John Bolton was notably audacious in trying to impose his will on the President, and he was not alone. As former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley noted in her new memoir With All Due Respect, “In every meeting of the president’s cabinet and national security advisors, there was a faction that seemed to think they, not the president, should make the final decision when it came to policy.” According to Haley, former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and former White House Chief of Staff John F. Kelly tried to recruit her to subvert Trump to save the country: “It was their decisions, not the president’s, that were in the best interests of America, they said. The president didn’t know what he was doing.”

The ambition to make policy decisions, rather than merely execute them, is present among middle-ranking bureaucrats more starkly than ever before. In testimony before the House Intelligence Committee, Ukrainian-born Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman said that he was “extremely disturbed” by Trump’s phone conversation with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. Vindman thought he was authorized to nurture “bipartisan support” for U.S. policy in Ukraine, and to treat the country of his birth as essential to America’s national security. In the same spirit the U.S. ambassador to the European Union, Gordon Sondland, declared that State Department personnel “should take responsibility for all aspects of U.S. foreign policy toward Ukraine.”

The striving of unelected officials to usurp presidential powers is all-pervasive now, with serious implications for the conduct of U.S. foreign policy. There is no comparable case in modern diplomatic history of a major power undermining its own status as a unitary actor.

Mikhail Gorbachev’s dismantling of the Soviet Bloc and Deng Xiaoping’s radical reforms ran counter to the preferences of many old-guard apparatchiks, yet there was no sustained resistance on a comparable scale. The U.K. Foreign Office is mostly staffed by pro-EU remainers, but they have refrained from staging a systemic obstruction of Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s Brexit agenda. On a smaller scale, President F.W. de Klerk’s momentous decision to dismantle apartheid was not resisted by South Africa’s solidly white senior bureaucrats and uniformed officers.

It is in the American interest that Trump survives impeachment and wins in November. If he does, a purge of the mandarins and their lower-ranking fellow travelers in the diplomatic, security, and intelligence services should top his agenda.

For as long as the neocon-neolib hydra remains in place, Trump’s attempts to turn America into a normal, non-missionary nation-among-nations will be thwarted; neither the U.S. nor the world will be safe from their millenarian urge to “engage” America in pursuit of universal ideals. Its pernicious role is inseparable from the impeachment farce: in both cases, the elite class has subverted the law and voters’ will in order to assert its power. Machina delenda est should be Trump’s motto.

Leave a Reply