I first heard Roger Scruton speak at the 1993 regional Philadelphia Society meeting in Dearborn, Michigan, organized to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Russell Kirk’s The Conservative Mind. Scruton spoke on the topic of “The Conservative Mind Abroad” in a soft but authoritative voice that gently drew and kept the listener’s attention. However, his professorial demeanor never got in the way of making a forceful point. This was demonstrated in 1997 at a debate in London sponsored by the Edmund Burke Society. I was invited to attend the bicentennial celebration of Burke’s death and the festivities included a debate over his continued relevance.

As a dutiful managing editor, I cornered Scruton at the reception afterwards to invite him to write for Modern Age, knowing full well that by that point in his career he had plenty of venues in which to publish his writing. Scruton finally appeared in Modern Age 10 years later—in the 50th anniversary issue no less—with an exceptional essay I commissioned on a subject few conservatives had the intellectual wherewithal to pull off: “Conservatism Means Conservation.”

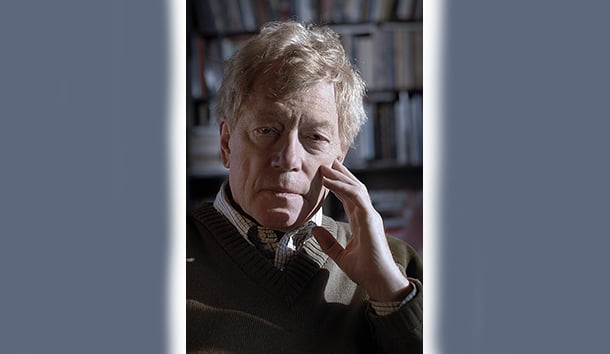

Scruton’s death on Jan. 12 of cancer at the age of 75 was a great loss for our civilization. He was a prolific, trailblazing man of letters—particularly in the United Kingdom, where philosophical conservatism had long been ridiculed and banished from polite society. Conservative ideas regained respectability in the U.K. over time due in part to his influence.

After growing up in a working class family, Scruton studied modern philosophy at Cambridge, and in 1968 while teaching in France, found himself repulsed by the Paris youth uprisings, an experience which turned him into a conservative. In 1971 he secured a post at Birkbeck College, London, where he was professor of aesthetics. He was the only conservative on the faculty and his colleagues made sure that his was a lonely existence. He began a journey of discovery into philosophical conservatism in the 1970s while studying for the bar exam—he completed his courses but never practiced. At the time there were many intellectuals on the right in America, but in Britain, wrote Scruton, “conservative philosophy was the preoccupation of a few half-mad recluses.” It was during those years that he discovered Burke.

Burke helped to explain the violence and mayhem that Scruton observed in Paris in 1968. His decade-long investigation into Burkean conservative principles came to fruition in The Meaning of Conservatism, published in 1980. This was his third book, and Scruton’s style needed much refinement. Years later he would confess, “I am embarrassed by quite a bit of it now.” Even so, it made a splash, for good and for ill. He wrote in recollection that the book’s “Hegelian defence of Tory values…blighted what remained of my academic career.” Despite left-wing outrage, the book found readers, and was written primarily for the free marketeers and libertarians who supported Margaret Thatcher. Scruton said he was “trying to say that conservatism is something other than what they believed it to be.”

In the ’70s, Scruton’s interest in creating a foundation for British conservatism had led him to join Sir Hugh Fraser, a Conservative MP, in founding the Conservative Philosophy Group, established in 1974 to cultivate a deeper appreciation for conservative principles among Tory MPs. Its failure to transform the Conservative party during the group’s 20-year existence was predicted by Maurice Cowling, the eccentric Cambridge University historian, who told Scruton that conservatism was “a political practice, the legacy of a long tradition of pragmatic decision-making and high-toned contempt for human folly.” Only naive Americans, asserted Cowling, would attempt to turn it into a philosophy.

Undaunted, Scruton eventually became the first editor of The Salisbury Review, founded in 1984. Samizdat versions of the journal began to appear in Eastern Europe, and this led to invitations for private lectures from freedom-starved intellectuals living behind the Iron Curtain. The dissidents to whom he offered intellectual and moral support would honor him when they gained power after 1989. For example, Václav Havel, when president of the Czech Republic in 1998, awarded Scruton the Medal of Merit for his service to the Czech people. When not sowing seeds of dissension in Communist lands, he was raising a ruckus as a weekly columnist for The Times of London from 1983 to 1986.

One of Scruton’s most adversarial books was Sexual Desire, a 1986 rejoinder to Michel Foucault’s The History of Sexuality (1976), which Scruton called “mendacious.” Scruton had discovered Foucault during his time in Paris, and said that the French radicals he had encountered there used Foucault’s theories to “justify every form of transgression, by showing that obedience is merely defeat.” English law, Scruton believed, is the answer to Foucault. “The common law of England is proof that there is a real distinction between legitimate and illegitimate power, that power can exist without oppression, and that authority is a living force in human conduct,” he wrote in his 2005 memoir Gentle Regrets: Thoughts from a Life.

Of the 50-odd books to his name, Scruton was most proud of The Aesthetics of Music (1997), a work primarily based on his philosophy of music lectures delivered during his three-year visiting professorship at Boston University. Music was of more than just academic interest for Scruton. He was also an organist and a composer of several libretti, two of which he set to music. One of these was a two-act opera entitled Violet, based on the life of British harpsichordist Violet Gordon-Woodhouse, twice performed in London in 2005.

In 1995 he abandoned Boston and full-time academic teaching to take up popular writing. More than ever, the academically trained author applied his philosophical mind to current concerns. Against Tony Blair’s fox-hunting ban, Scruton wrote Animal Rights and Wrongs (1996) and On Hunting (1998). His Green Philosophy (2012) targeted environmental studies.

When he discovered culture as a young man, Scruton sought out modern music, poetry, painting, and novels. But he could not abide modern architecture. In Scruton’s view, the modernist pioneers were “social and political activists who wished to squeeze the disorderly human material that constitutes a city into a socialist straitjacket.” His first scholarly treatment of the subject was The Aesthetics of Architecture (1979). He actively supported the preservation movement in England, and at the Bath Preservation Trust he met Sophie Jeffreys, an architectural historian, who would become his second wife and mother of his two children.

Scruton’s full awareness of the importance of religion developed late in his life, though he had been drawn much earlier to the Latin liturgy and traditional architecture and developed an intellectual appreciation for Catholic teaching. Even so, he readily admitted that he had trouble believing in God’s existence. Moreover, he was dismayed by the iconoclasm that swept through the Catholic Church after the Second Vatican Council. Years later, his faith restored, he came to worship in a small Anglican chapel where he played the organ. In The Face of God: The Gifford Lectures (2012), he challenged atheistic culture by arguing for human uniqueness and for the existence of meaning and purpose in the world. In The Soul of the World (2014), he defended the sacred against assaults from fashionable manifestations of unbelief.

Scruton’s personal story and intellectual contribution are discussed in Gentle Regrets and in Conversations with Roger Scruton (2016), edited by Mark Dooley. The philosophical underpinnings of his conservatism were informed by the insights of modern authors. In defense of human nature and human freedom rightly understood, he used those insights to develop arguments against the worst excesses of the political left.

Traditional conservatives know that politics is downstream of culture. While establishment conservatives ignored the treacherous left-wing assault on the foundations of Western civilization, Scruton fought an often solitary battle on behalf of our cherished customs and institutions. If we ever hope to conserve what is good, true and beautiful, we will need more culture warriors like Roger Scruton.

Leave a Reply