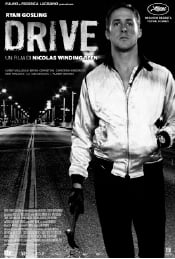

Drive

Produced by Bold Films and Odd Lot Entertainment

Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn

Screenplay by Hossein Amini from the novel by James Sallis

Distributed by Film District

At the close of George Stevens’ 1953 big-screen version of Jack Schaefer’s novel, Shane, ten-year-old Joey Starrett (Brandon De Wilde) called repeatedly to his wounded idol, “Shane, come back,” as the saintly gunslinger rode into the mountains surrounding the Wyoming valley in which Joey and his parents lived. Joey’s plaintive appeal proved unavailing. Shane (Alan Ladd at his stoic best) kept riding into the hazy distance, having completed his mission. He had just saved Joey’s imperiled family by facing down evil in the person of the demonic Wilson (Jack Palance), a hired gun retained by the territory’s cattle baron. It was now time to ride away so that he could be with the Starretts in spirit forevermore.

Schaefer’s novel and Stevens’ film were elegant reworkings of the Christ story set in 1880’s Wyoming, complete with echoes of crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension. It’s a wonder that the ACLU didn’t sue Paramount for scandalizing the filmgoing public.

Today, it seems there’s more saving to be done, for Shane has at long last heeded Joey’s call and come back. Last month, I reviewed John McDonagh’s film The Guard, in which Brendan Gleeson, playing a Connemara constable, steps somewhat heavily into Shane’s boots, girding his expansive gut with his pistol belt and giving his policeman’s cap a determined tilt before waddling out to face the old enemy. There’s even a boy of ten attending Gleeson’s showdown at a distance, convinced that, whatever the outcome, the big guy will come back.

Now comes Danish-American director Nicolas Winding Refn’s highly stylized and self-serious film Drive, adapted from a novel by James Sallis, in which Ryan Gosling has taken up Shane’s burden. In case you haven’t noticed, this is the movie much of the advanced critical community has been trumpeting. Gosling plays a loner, conspicuously unnamed, who shows up at Bryan Cranston’s Los Angeles auto-repair garage without a shred of personal history in tow. This is OK by Cranston because the young man’s an ace at repairing cars and is willing to drive exquisitely for pay, regardless who’s hiring: film studios in need of auto-vehicular stunt work or gangsters looking for spectacular scores. Driver, as he’s referenced in the film, is an existentialist whose identity is constituted not by who he is but by what he does. In a word, he’s cool. You can tell by his nearly expressionless face and soft, uninflected voice.

Driver is as extraordinarily handy with cars as Shane was with guns. He’s a professional’s professional, as we learn in the opening sequence, in which he drives two thieves to their larcenous appointment with a Staples office-supply store, informing them beforehand of his driving rules: “You give me a time and a place. I give you a five-minute window; anything happens in that five minutes and I’m yours no matter what. . . . I don’t carry a gun. I drive.”

Driver embraces a purely instrumental ethic. Not so Refn, who takes pains to make sure we don’t get the wrong idea. He doesn’t want us to think he’s made a mindless action film. To that end, he begins the proceedings with an agonizingly slow getaway from the Staples holdup. Rather than swerving through L.A. on two wheels, with the cops in squealing pursuit, Driver calmly navigates his souped-up Impala as though he were a thrifty suburbanite trying to save on gas. He’d rather evade the cops than race them. Why challenge the local constabulary when you can outwit them? He goes about his task quietly, only revving his engine when absolutely necessary, as when he dodges under a handy freeway ramp in order to hide from a couple of pursuing squad cars. He watches from the shadows with icy regard as the cops whiz right past him. Then he drives at an almost leisurely pace to his clients’ drop-off destination. This is not the kind of car shenanigans that built the careers of Steve McQueen and Mel Gibson. While such restraint is commendable, it seems at first a bit starchy for what is, apparently, a genre movie. But then the Shane business kicks in, and you realize you’re not watching some dumbass chaser, but a serious film.

Shane explained to young Joey that a gun is just a tool, only as bad or good as the man who wields it. So, too, the cars Driver wields. While we witness him using them for criminal purposes, they’re not his purposes but those of others. He’s a knight errant in a debased world who, in the absence of worthy quests, occasionally sells his expert services to the bad guys, while remaining antiseptically insulated from them. Then he meets Irene (Carey Mulligan) and her son, Benicio (Kaden Leos), who live down the hall from his nondescript, industrial-zone apartment. Once they enter his life, he has a quest worthy of his talent.

Irene is attached, sort of, to Standard (Oscar Isaac), the child’s father, now in prison for thievery. Despite having formed such a dubious alliance, Irene, as you would expect, is sweetness itself. She displays such devotion to her boy that she quickly wins Driver’s innately noble heart, and he begins courting her in a studiously chaste manner. “Would you like to take a drive or something?” he asks her, laconic to the point of being nearly inarticulate. He takes her and the boy—whose name means “blessed,” in case you were wondering—to the Los Angeles River Drainage Basin in which so many biker films have been set, including the Terminator’s motorcycle chase. Once there, he drives them through some of the concrete channels at speeds well within the legal limit. He’s no “hasta la vista” Terminator; he’s a hero who sees things through, as the soundtrack embarrassingly emphasizes with a syrupy song by Electric Youth featuring the lyrics “A real human being, and a real hero.”

As Driver continues to visit Irene, he finds, as did Shane before him, that he’s acquired an obligation. When he discovers Irene’s husband is being hounded by thugs after he comes home from prison, his first instinct is to help the hapless fellow for Irene’s sake. The thugs are pressuring Standard to pull one last robbery. Driver decides to lend his services in order to make sure Standard comes home to his family. Unless you’ve been away from the movies for the past 75 years or so, you’ll know what’s going to happen next.

I’m all for hero stories, especially those draped in Christian allusions. But I had a problem with this film. It’s too mannered, too impressed with itself to be as fully engaging as it could have been. In short, it’s egregiously self-regarding. Refn spends a good deal of time cuing the audience that they’re in the presence not of mere entertainment but of genuine Art. He paces his plot glacially and overly arranges scenes (every time Gosling is driving, he’s shot from the level of his car’s floor so that he looks monumental behind the wheel). The characters have been given self-reflexive commentary to spout. Albert Brooks, playing a jaded Jewish gangster with various interests, none of them completely legal, decides to back Driver’s NASCAR ambitions. As they discuss plans, he tells Driver for no discernible reason that he once made movies in the 80’s. “Action stuff,” he explains. “One critic called them European,” he recalls almost wanly before turning acid. “I thought they were shit.” It’s an amusing moment, but it has nothing to do with the story and everything to do with Refn’s evident need to signal us that he has made something far superior to a commercial entertainment. Frankly, I would have enjoyed a little crass commercialism by this point. The slow pace of both the cars and the film is meant, I suppose, to make things more realistic, but, oddly, it undermines verisimilitude. We’re given far too much time to ask questions we shouldn’t. Why would Driver, the consummate professional, take up with a woman so obviously compromised as Irene? Why would he so quickly offer to assist Standard with a harebrained robbery? And why would Ron Perlman, playing Brooks’ criminal partner, run into the Santa Monica surf to escape a determinedly lethal pursuer? Wouldn’t the beach and boardwalk have offered far more negotiable terrains on which to attempt his escape? I’ll answer this last question with recourse to film history. Refn’s scene pays tribute to Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly, another film that has been hailed as European by cineastes, and shit by others. In its conclusion, Aldrich has his antihero Mike Hammer running desperately into the same Santa Monica surf to escape the ultimate pursuer, an atomic explosion. It seems Refn is waging a rear-guard action by means of cinematic quotation. As Driver descends into the criminal world without being contaminated by it, Refn wants us to know that although he has descended into the sordid tropes of film noir there’s no reason to suppose his work is defined by them.

Refn, Danish by birth and American by choice, was trained in the cinema of both nations and clearly loves his medium. His moody lighting, lengthy tracking shots, and elliptical dialogue all declare his devotion to his art. But it’s not enough to love your medium’s strategies. A successful director must love his story enough to serve its interests before all other considerations. Refn is not in love with his story; he’s in love with his cinematic rendering of his story. The distinction is critical.

There’s much that’s interesting in this film, and I’m not surprised it has enraptured the more thoughtful among young filmgoers. I think it a good sign when a film deploying an allegory such as Drive does connects with its audience. Nevertheless, I found Refn too self-regarding to engage me. I’ve never cared for directors who constantly ask us to be dazzled by their artistic choices.

Leave a Reply