Gone Girl

Produced by New Regency Pictures

Directed by David Fincher

Screenplay by Gillian Flynn, from her novel

Distributed by Twentieth Century Fox

If only James Thurber were still with us. I’d love to hear him address Gone Girl, both Gillian Flynn’s novel and David Fincher’s film adaptation thereof. Why? Because the story trades on Thurber’s central theme: the perpetual war between men and women. Admittedly, Flynn has rendered this chestnut with a far more savagely satiric sheen than Thurber would ever have allowed. Flynn has brought to the party a particularly mordant, not to say homicidal, tincture. Still, like Thurber, her aim has been to create a stylized whammy of sexual impertinence. Unfortunately, Fincher’s talents don’t run to satire. He’s clumsily literalized everything in sight.

Both the novel and the film, however, do manage to convey Thurber’s view that, while men might win a battle in the sex wars now and then, ultimate feminine victory is never in serious doubt. Thurber knew that on the field of battle men were no match for the guileful tactics deployed by women. Not heterosexual men, anyway. Give the merest glimpse of feminine beauty, the heterosexual male is likely to sink into a libidinous lather quite inimical to reason. Men should know better, but desire easily beclouds their minds. Fortunately, most women regard such male helplessness as a charming tribute and are thus inclined to go easy on the inferior sex. But, as the practitioners of noir fiction have illustrated, such courtesy is far from universal.

Gone Girl is an admirably wicked satire on love and marriage that lays waste to all the currently correct notions concerning sexual equality. That’s why Flynn’s being excoriated in some quarters. She has not hewed to the feminist line. It’s also, I suspect, the reason her general audience is so delighted by her. Whatever they will say publicly, heterosexuals in both camps know innately that today’s officially approved sexual politics are sheer malarkey. In the 18th century Samuel Johnson could remark that “nature has given women so much power that the law has very wisely given them little.” To say or even cite these words today would be to invite moral condemnation followed swiftly by ruinous legal action.

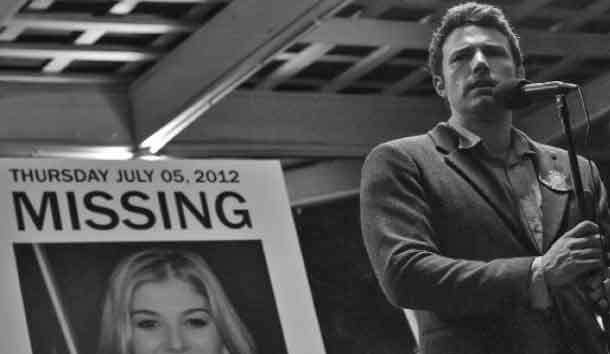

Following Flynn’s screenplay, Fincher’s film opens with Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) looking down on the back of a beguiling blonde head resting on his knee. It belongs to Amy (Rosamund Pike), his wife. What, he wonders alarmingly, would he find if he cracked open this lovely skull and unspooled the brain inside? The rest of the film does just that: It opens Amy’s skull and examines its curious innards.

Amy is a woman in her late 20’s, the only child of parents who make their living as psychotherapists while pursuing a profitable avocation. They write children’s books featuring a little girl whom they’ve named Amazing Amy, as if in honor of their only child. Sounds cuter than bone buttons, doesn’t it? There’s just one problem: In their stories, Amazing Amy leaves the real Amy panting hopelessly behind her. Whereas the flesh-and-blood Amy stumbles on the soccer field, Amazing Amy scores goal after goal. Amy tires of her piano lessons and quits upon starting middle school. Amazing Amy, though weary of the keyboard, perseveres nevertheless. Needless to say, Amazing Amy’s recitals go on to win her applause and honors, while real Amy must bear her parents’ smiling reassurances that it’s quite all right to quit if that’s what she really wants to do.

With such monstrously passive-aggressive parents, we’re left to infer, Amy’s every rebellious instinct has been thwarted in advance. As a result, she’s gone quietly mad under a perfectly varnished veneer of obliging pleasantness.

This explains what happens when Nick shows up. Amy immediately recognizes him as the weapon she needs to avenge herself. He couldn’t be farther from her parents’ idea of Prince Charming. He carries himself in a boorish, almost thuggish manner. His ambition registers on his personal Richter scale just a few degrees above zero. His notion of romantic dalliance is to hike up Amy’s skirt and perform oral sex on her between the stacks of a public library, while more scholarly inclined patrons search for books in the neighboring shelves. Sprawled on a table, she’s so pleased she interrupts his erotic efforts to tell him she really, really likes him. It’s obvious what she’s actually thinking: Wait till you get a load of this guy, Mom and Dad.

If Amy is delusional, so is Nick. How could he miss seeing there’s something screwy about his new inamorata? But, like so many other young men, Nick hasn’t the imagination to look further than the moment’s rutting. So when we jump ahead to the fifth anniversary of their marriage, we’re not entirely surprised to learn that their union has begun to unravel. They’ve lost their jobs in New York and moved to Nick’s Missouri hometown to take care of his mother in her final days. This becomes yet another of Amy’s disappointments. She’s falling even further behind Amazing Amy.

To say more would be to give away too much. Suffice it to say that things go absolutely bizarro when Amy goes missing and Nick is suspected of foul play. In a media-driven society, this spells carnival time, especially when Nick is revealed to be an adulterer. It’s this part of the film that I found most interesting. Flynn’s screenplay and Fincher’s direction finally come together to dramatize the sheer nuttiness of American life viewed under the tyrannical assumptions of popular culture. But be warned. Even by today’s abysmal standards, this movie has scenes of sexual excess and rabid brutality that would turn James M. Cain’s morally weathered cheeks scarlet. In this respect, Gone Girl is thoroughly gone.

The performances are all very good. Pike couldn’t be better as Amy—cute and perky as a kewpie with a rich hint of lunacy behind a plasticine visage. Affleck is stolid and stiff as usual, but this is just what the story requires. He’s a fellow adrift in his own stupidity. I was especially surprised by Tyler Perry playing an astronomically priced defense attorney. He’s hilarious as the kind of officially condoned black con artist operating just this side of the law.

Leave a Reply