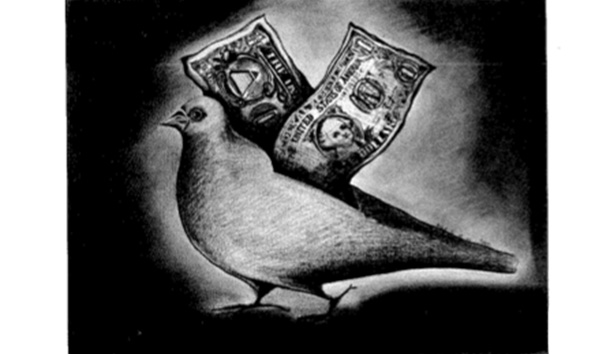

Peace is busting out all over, and along with the prospect of peace comes the debate over how to spend the so-called “peace dividend,” supposing there is such a dividend. The administration doesn’t think there is, and Secretary of Defense Cheney has warned against spending the money saved on defense until it is in the bank. Some commentators have estimated that the savings could amount to more than $200 billion by 1995, and the Democrats are already devising schemes to buy more constituencies by spending more on domestic programs. The administration, on the other hand, has argued that whatever pittance is realized should be applied to the deficit in the short run and, in the long run, to the national debt.

All things considered, the Democrats have been surprisingly quiet on the subject. A few years ago they would have been holding hearings and summoning the President’s men to account, but these days all we hear are gentle “spendmore” bromides from unrepentant leftists like Senator Paul Simon of Illinois. Robert Zelnick, himself a graduate from Northeastern People’s Radio to ABC, is disappointed and quite correctly suggests that “along with five out of the past six Presidential elections. Democrats have lost their political nerve.”

But if leftists are bewildered by recent events in Europe, conservatives are equally disorganized. To understand why. it is necessary to realize how much both sides have invested into the Cold War. It is no exaggeration to say that much of postwar American conservatism has been little more than McCarthyism writ large, since many conservative groups have occupied themselves primarily in opposing the spread of communism abroad and the increase of socialism at home. At the same time, the left has devoted itself to opposing anticommunism, by favoring the sovietization of the United States and by working for a foreign policy of submission and disarmament.

Whatever the reality of the situation in the U.S.S.R., the Cold War is over for the time being, and both conservatives and leftists find themselves at loose ends as rebels without a cause. For some groups, this means bankruptcy, and not of the merely moral variety. Conservative fund-raiser Bruce Eberle told the New York Times that “there’s much less interest” in anticommunism as an issue, and many anticommunist organizations are already feeling the crunch. But the peace and disarmament groups aren’t doing any better. Nuclear Times is out of business and membership is plummeting at SANE/Freeze. As former arms negotiator Paul Warnke observed, decommunization has done to the peace movement “what the Salk vaccine did for the March of Dimes.”

The collapse of communism, anticommunism, and anti-anticommunism brings us back to where we left off in the 1940’s, before the United States divided up into two warring camps of left and right. It was an age when most “conservatives” persisted in calling themselves liberal—Albert Jay Nock and Robert Taft, to name only two—and the great conservative themes were limited government, low taxes, the autonomy of state and local governments, and “isolationism,” which was nothing more sinister than the determination to leave other nations, respectfully, alone. Many of these old conservatives had opposed America’s entry into World War II, nearly all had supported the war effort, and all deplored the concentration of state power that Franklin Roosevelt had managed under the guise of emergency measures for national defense.

There was no conservative movement in those days, but there were learned men of conservative principle; individualists of the stripe of Mencken and Nock, and most prominent among them was Frank Chodorov; such Southern agrarians as Donald Davidson and Richard Weaver; and the desperate ex-Communist Whittaker Chambers. Some conservative writers in those days managed to carve out successful careers as scholars and journalists, but many realized that, if they wished to speak frankly about politics, economics, and history, they could never hope to be acceptable, much less popular. Senator McCarthy, Chambers, and the other anticommunists were abused and reviled by Edward R. Murrow and the other propagandists who still run CBS News. Mencken is even now being libeled by the literary journalists who make a career out of character assassination and sycophancy, and the youthful William F. Buckley, Jr. found himself being mocked and mimicked by Jack Paar on live television after he had made a brief appearance on the Tonight Show.

The poet Robinson Jeffers, although by no means typical of anything, was representative. Hating Roosevelt’s policies as subversive of everything distinctively American and blaming him for dragging us into “the war we have carefully for years provoked,” Jeffers railed against the men who were “plotting to kill a million boys for a dead dream.” He, nonetheless, applauded Britain’s heroic fight against the Germans and resigned himself both to the war and to the barbarization he knew would follow. In “I Shall Laugh Purely,” he assumed the prophetic mantle. These convulsions were not the end of the world, or even of our civilization—that would take years. But,

[we] shall beware of wild dogs in Europe and of the police in armed imperial America:—

Jeffers hoped Christendom would “go down in conclusive war and a great red sunset” and not linger like India, “old and holy and paralytic.” In a reprise of his great early poem, “Shine, Perishing Republic,” Jeffers delivered his final verdict on the republican experiment he still cherished:

I have often in weak moments thought of this people as

something higher than the natural run of the earth.

I was quite wrong; we are lower.

We are the people who

hope to win wars with money as we win elections.

For his views on Roosevelt, Jeffers was excommunicated from America’s literary pantheon, and to this day his work is studiously ignored by critics. Even his publisher, Bennett Cerf at Random House, lent his hand by inserting into a Jeffers volume a preface that condemned the poet’s political views.

What Jeffers would say about America in the 1980’s, it is neither difficult nor pleasant to imagine: a nation of lewd consumers, cripples leaning upon electronic crutches; a population addicted to drugs and sex at the upper and lower ends, while the saving remnant in the responsible middling classes is a dwindling minority; a nation where men of principle and learning are despised, Donald Trump admired, and athletes adored.

Poets are always extremists, and there remains much to celebrate in contemporary American life, but we are dishonest or obtuse if we refuse to recognize something of ourselves in Jeffers’ picture. But now that “armed imperial America” is preparing to disarm, what is next? In particular, what are conservatives going to do, after winning the good and necessary fight and goading several administrations into opposing the Soviets, much as Aaron and Hur propped up the arms of Moses?

Terrified over the loss of their one trump card—the Soviet threat—some conservative power brokers are floundering desperately for issues: the drug war, democratic globalism, and minority rights. If you think these sound like recycled liberal issues, then you might also think there is something strange about a conservative leader whose model for the movement is “the great Democratic New Deal Party.” U.S. News & World Report described this and other newly respectable conservatives as “suddenly sounding oddly like Democrats.”

Now, if ever, is the time for conservatives, liberals, and even radicals to think through where they stand in the hope of forging new and principled alliances to replace the old, bankrupt coalitions of anticommunism and anti-anticommunism. Now, more than ever, there is a pressing need for a free and open debate. Unfortunately, a vigorous discussion is highly unlikely. The left seems permanently wedded to anti-Americanism and countercultural resentment, and conservatives who dissent from the ever-changing orthodoxy of Washington—and even those who only lag behind in embracing the party line—are read out of “the conversation” or consigned to the inner circles of “the fever swamp,” a term used by Suzanne Garment and other East Coast conservatives to designate the yahoos, rednecks, and Nazis that inhabit middle Amerika.

There is nothing new about attacks on conservatives. In the 1950’s conservatives were repeatedly called bigots, nativists, and fascists, and it did not seem to do them a great deal of harm. Of course, in those days it was the liberals doing the name-calling; today, it is people who insist upon calling themselves conservatives, usually “progressive conservatives” and “neoconservatives.” The so-called coalition they worry so much about in Washington is falling apart, and it will take more than the shoddy plaster of slogans and marching orders to fix up bridges that are so badly in need of repair.

What is really going on in conservative circles cannot be divided up into neatly labeled camps of traditionalist, neoconservative, New Right, and libertarian. There are, however, a number of themes or approaches, in part philosophical and in part political, that do recur in the writings of self-described conservative thinkers of the 1980’s. Three of them, in various permutations and combinations, might serve to explain the movement.

1. Reaction. To one extent or another, most conservatives (like most radicals) define themselves by the golden age they are pining to restore. For Richard Weaver it was the High Middle Ages; for other Southerners it was the antebellum South; for many Cold War anticommunists, it was a period some time before FDR, when the U.S. still enjoyed a republican form of government; for the neoconservatives, it tends to be the period from Roosevelt through Kennedy. Whatever their period of choice, reactionaries recognize, at least implicitly, the importance of historical myths in shaping the world view and political agenda of the present, and no conservative movement will get anywhere until it can put together something like a coherent myth of the past.

2. Conservation. Conservatives by definition are conservative, that is, they believe there are elements in the present political arrangements that are worth preserving. For neoconservatives it is some sober version of the welfare state; for traditional conservatives it is the vestiges of limited government, autonomous families, and Anglo-American civilization.

3. Progress. Until fairly recently, one did not hear much about the future or growth or progress from rightists or conservatives anywhere. In America, however, no cultural or political movement can afford to do without a positive vision of the future, if only because Americans in the 20th century have been, by and large, dopey progressives. Many otherwise sensible people find the idea of a “conservative opportunity society” irresistible and call for “no limits to growth” almost in the same breath that they are defending the “values of Judeo-Christian civilization.” The doctrine of progress, in its current forms, celebrates technology, economic growth, free trade, global democracy, and open borders. All of this is repellent, to earlier generations of conservatives, who have made a serious tactical error in rejecting the spirit of progress out of hand. The best quality of our own civilization—I do not say the best quality of any civilization—has been an exuberant confidence in our ability to solve problems, although we rarely take the time to reflect that most of these problems are the result of earlier solutions.

These themes cross all boundaries and hostile frontiers, and several can turn up in the same man: George Gilder’s entire career looks like a sort of juggling act between reaction and progress, and while I frequently disagree with him, there is no political journalist I admire more. The task that lies before conservatives, it seems to me, is to come up with a framework that combines these three approaches in a fashion that is faithful to the most essential principles and will serve the needs of the post-Cold War America.

I have neither the space nor the inclination to sketch even the most general lineaments of such a synthesis. Instead, let me concentrate on one issue as a metaphor: the environment. Except for libertarians, conservatives really don’t have an environmental ethic, and Chronicles intends to make an attempt at remedying that deficiency in our August number. However, the three themes of reaction, conservation, and progress do serve to define the most common approaches to environmentalism.

At one end of the spectrum is the reactionary agrarian—sometimes Luddite in the intensity of his hostility toward technology, population growth, and pollution. On this Christian conservatives, like Wendell Berry and Jacques Ellul, shake hands with hard-bitten leftists, like Jeremy Rifkin. Once upon a time, so the myth runs, the waters were clean, the air pure, and the forests magnificent. Human technology, such as it was, worked in the service of man and nature. Today, with technology in the saddle, man is servant to the machine that has befouled his air and water, deforested the landscape, and covered the coasts of our continent with ugly suburban sprawl. So runs the myth, and like most myths it is true in its essentials.

The conservative approach is aptly called “conservation” or “preservation.” Although the imagination of conservationists is typically fired by a reactionary rustic vision, the approach is not so much a question of opting out or returning to the land, in the manner of Wendell Berry. Conservationists want to preserve our dwindling resources by establishing and maintaining forests and wilderness preserves from which human influence is excluded and in which human activity is sharply curtailed. While conservationists might prefer a better world, they will settle for conserving what we have.

The party of progress and growth rarely sees any real environmental problems, and what few difficulties exist can be settled by an exclusively free market approach in which dirty industries may buy some of the unused pollution rights of clean factories. Is the air of Los Angeles unbreathable? Then the solution is better technology, not more regulation, because regulation, in fact, has almost always done more harm than good.

My point, in drawing out the example, is this. Both the reactionaries and the progressives have a great deal to contribute to the debate, while the conservationists—call them conservatives—are, because of their obsession with the status quo, unable to respond creatively to environmental crises and opportunities. Radicals and reactionaries are both capable of changing things for the better, while it is in the nature of conservatives to pamper a lingering illness rather than take a chance on a cure.

There is, however, a new environmental movement, one that concentrates on restoration, not preservation. Restoration of a prairie or a forest requires all the tools that science and technology can supply; it also requires the hard work, ingenuity, and creativity of thousands, indeed millions, of human beings. Rather than excluding man from the wilderness as something vile, restoration work drags people out of the suburbs and into the fields, where they will learn once again to play the role of Adam, this time restoring and not just tending the garden. Of course, a restored prairie is not the same thing as a primitive prairie; man is now part of the equation and has a part to play, and only a resolute enemy of mankind will object.

Some aspects of this example cannot be applied to the general plight of conservatives. More can be. Like it or not, we live in the late 20th century, and while we cannot do without the myths of historical golden ages, we must recognize that the attempt to realize those myths will produce results that bear only a slight resemblance to the 12th century or the 1850’s—least of all to the 1950’s. Both the Renaissance and the Reformation were reactionary movements aimed at restoring the world of antiquity. Both were radically constructive. Neither was—in a literal sense—conservative.

Perhaps it is time even to rethink the effectiveness of the term conservative, which always begs the question: “What are you conserving?” There is so much wrong with modern America that the language of caution seems inadequate. Surely it will take at least a moral and cultural revolution to clean up our cities, end the drug trade, and restore civilization.

Call yourself what you like, but be sure of this. Nothing good can be done on the basis of a simple formula derived from the experiences of the Cold War years. Global anticommunism cannot be replaced with global democracy, and the left’s dreams of world government cannot be countered with a state-capitalist vision of a world economic order. Our job is to restore America, not to convert the world, and this task will require all the resources of science, economics, and technology we have at our disposal, but those resources must be harnessed to serve the traditions of individual responsibility, starkly limited national government, and the rich diversity of local political arrangements that our Constitution was intended to preserve.

What I have in mind is both reactionary, in its appeal to the vision of America’s founding, and radical, in its willingness to use the honest tools and weapons put into our hands by sociobiology, anthropology, and economics. What all of these technical disciplines reveal is a humanity that is both flawed (or self-interested) in conception and yet most creative when least coerced. Both science and traditional wisdom will also show us that government, while it is necessary for men in every stage of social development, can only be regulatory and limiting; it cannot produce anything of itself the more laws a people has, the more corrupt its morals.

This is the prospect for America’s public intellectuals, especially those who have called themselves conservatives: to begin the arduous task of reconverting a blighted social and cultural landscape into prairies, villages, towns, and cities and to restore the self-government that has been polluted by the centralized political machinery that has misappropriated the name of democracy. If we fail—and nothing in the past ten years suggests that we are not failing miserably—then let us go down in honorable defeat, without calling, our disaster a victory and without changing our colors in a pathetic effort to join the winning side. Of course your enemies will lie about you, because that is the universal fate of honest men. As Jeffers told his own generation:

That public men publish falsehoods

Is nothing new. That America must accept

Like the historical republics corruption and empire

Has been known for years.

Be angry at the sun for setting

If these things anger you.

Leave a Reply