The road to hell, I was taught as a child, is paved with good intentions. Surely no one could fault the intentions of the Reverend Ralph David Abernathy—Martin Luther King’s right arm and successor in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference—as revealed in this fascinating and moving autobiography. Inspired by faith in Divine mercy, by a Christian vision of brotherhood among the races, and by hope of succor for the poor, the weak, and the oppressed, Abernathy has devoted his life to the cause unstintingly, courageously, even heroically. Moreover, grand as this dream may have been, it was the moderate position in the context of the civil rights movement of the 1960’s, even as SCLC’s advocacy of nonviolent demonstrations was the tactic of moderation. SCLC stood midway between an older generation that preferred not to rock the boat and a younger one, led by the likes of Rap Brown and Stokely Carmichael, whose counsel was “Burn, baby, burn.”

But the enterprise was inherently flawed. For openers, almost extra-human discipline was required to keep nonviolent demonstrations nonviolent, and though SCLC managed to do so for a while, the movement ultimately and inevitably got out of hand. The riots in Watts (about which Abernathy is strangely silent) followed the last great peaceful march at Selma by only five months. And even in the most controlled phases of the movement, there was something intrinsically violent in the massing of protesters; by Abernathy’s own account, though the demonstrators were carefully taught restraint, their purpose was to provoke a violent response by law enforcement officers and thus attract media attention and capture the sympathy of the nation. Finally, whatever the philosophical merits of civil disobedience, its destructiveness is potentially enormous, for any society that is restrained only by individual conscience inexorably degenerates into a Hobbesian state of nature.

Still, Abernathy and King were asking no more than they were constitutionally and morally entitled to, and, given everything, nonviolent resistance was possibly the only effective means available. Besides, it worked—for a time. The most difficult and most successful venture was that in Birmingham early in 1963. Despite court-decisions declaring that de jure segregation of public facilities was unconstitutional, Birmingham remained rigidly segregated, and its police commissioner. Bull Connor, was a brutally sadistic racist. But after weeks of daily demonstrations and continuous boycotts, the city’s business leaders negotiated a desegregation agreement. That campaign was followed in August by the march on Washington, where King gave his “I have a dream” speech before a crowd of 250,000, which in turn was followed by the enactment of the Public Accommodations Act of 1964. A year later came the march from Selma to Montgomery, which resulted in the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

That was the climax. Those in the center of the movement were soon to learn some painful lessons; for the walls that had come tumbling down were those of a Southern world that—the humiliations of Jim Crow and the brutality of Bull Connor notwithstanding—was a good deal kinder and gender than the world on the outside. The lessons began in 1966, when the SCLC invaded Chicago to form a coalition of black groups and “dramatize the plight of urban blacks to the decent people of Chicago and to the nation.” Instead, Abernathy and his associates encountered intense hatred—intra-as well as interracial—and a solidly entrenched system. Strange as it may seem, they had as yet experienced little of either. Abernathy’s description of his childhood will astound those who know the segregated South only as a stereotype. He had grown up in rural Alabama, surrounded by a loving (and disciplining) family. The one ugly racial incident in his youth came when a drunken white taunted and vaguely threatened him, but the drunk was quickly silenced by another white: “Don’t you touch that boy! That’s the son of W.L. Abernathy.” Abernathy served in a segregated unit in the Army during World War II, but he was discriminated against primarily as a Southerner, not as a black. During the demonstrations in the South, white officialdom had harshly maltreated the marchers, but with surprisingly few exceptions the white citizenry had looked passively upon their doings. By contrast, in Chicago, the Daley political machine neutralized them through co-option, while the white citizens, seething with rage, hurled epithets, bricks, and bottles at them. Even more shocking to Abernathy was the behavior of Chicago’s blacks. “We had no idea,” he writes, that black “gangs existed in Chicago . . . looting, robbing, raping, and terrorizing whole neighborhoods. . . . They had nothing but contempt for the church and for religion, which meant that we could not appeal to them.” Worse yet was the fierce hostility of black jailers, guards, and wardens: “It never occurred to me that blacks would hold such jobs and treat other blacks in such a manner.”

The harshest lessons came in Washington during the summer of 1968, shortly after King’s assassination, and took the form of challenges to Abernathy’s naive and endearing faith in the goodness of his fellow creatures. King had planned, and Abernathy carried out, a project called Resurrection City: he leased space in the Washington mall and erected a tent city, in which poor people of mixed race and ethnicity were to “live together in peace and mutual respect” for a few weeks, thus simultaneously impressing Congress with the plight of the poor and setting up a “model for the rest of the nation.” But things did not work out that way. First, a group of young blacks from Chicago and Detroit appeared, formed a gang, and set up a “protection business.” Then it turned out that the diverse groups—whites, blacks, Hispanics, Indians—flatly refused to be integrated. Even in that mini-village, “They not only preferred to live in separate groups, they insisted upon it.” Resurrection City ended as a fiasco, evoking no government response. And Abernathy came to a startling realization—”A good many people in government were quite happy with the status quo. They liked the idea of a huge, economically dependent population. The fact that there were third-generation welfare families pleased them.”

Abernathy headed the SCLC for eight more years, but for practical purposes the movement (and the book) was over. As for the book, it has been criticized for its comments about Martin Luther King’s sexual prowess, but that is a tangential matter that simply sets the record straight in a quiet way. As for the movement, it did help bring about a better South, for blacks and whites alike; and middle- and upper-class blacks elsewhere are perhaps better off. For the teeming masses, however, the urbanislums were already becoming a hell, and what the civil rights movement did for them was to prompt paternalistic legislation that made their hell permanent.

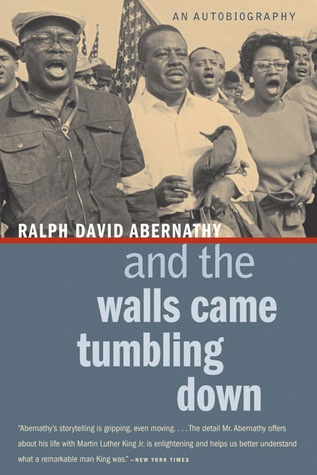

[And the Walls Came Tumbling Down, by Ralph David Abernathy (New York: Harper & Row) 638 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply