The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once mentioned the self-punishing limitations of his projected but never written autobiography: “I cannot write my biography on a higher plane than I exist on. And by the very fact of writing it I do not necessarily enhance myself; I may therefore even make myself dirtier than I was in the first place.” Mary McCarthy, paraphrasing Orwell’s essay on Salvador Dali, agrees that this genre demands a devastating honesty that often forces the writer to portray herself in a negative light: “an autobiography that does not tell something bad about the author cannot be any good.”

McCarthy was the American equivalent of the English bluestocking, Rebecca West. She was an extremely intelligent Latinate stylist, subversive satirist, and skeptical observer of social nuance; a novelist, travel writer, literary and theater critic who was passionately interested in politics and ideas. This memoir— more sexual than intellectual—is thin, gossipy, fragmentary, and clearly unfinished (many obscure friends are not identified). And the striking anecdotes are rarely developed into serious and significant events. Nevertheless, this is a ruthlessly self-critical and tantalizingly interesting book.

This brief work is organized around two conflicts: political and personal. It begins two years after McCarthy had graduated from Vassar, when she was beginning her literary career by writing severe reviews in the Nation and New Republic. Though only slightly attracted to communism, she drifted into the Partisan Review circle and was caught up, during the purge trials, in the fanatic ideological wars between the Stalinists and Trotskyites. Her mentors on Partisan were passionately pro-Trotsky, but she was far too intelligent to swallow the party line. As Scott Fitzgerald (to whom McCarthy bore a remarkable physical resemblance) observed of Edmund Wilson’s politics in the late 1930’s: “A decision to adopt Communism definitely, no matter how good for the soul, must of necessity be a saddening process for anyone who has ever tasted the intellectual pleasures of the world we live in.”

The young and beautiful McCarthy was also torn between husbands and lovers. She leaves her first husband, Johnsrud, but does not know why, and loses interest in her lover John Porter— whose main function was to dissolve her marriage—for equally vague reasons. Following the advice of an old teacher, she tried hard to “come to real love free of any neediness.” But, having been orphaned as a young child, she never succeeded in reaching this pure state and became quite miserable when poor, loverless, and lonely.

Her innumerable lovers included the original of the hero of her story “The Man in the Brooks Brothers Shirt” who worked for a plumbing company in Pittsburgh, and an earnest communist actor who wore lifts in his shoes. McCarthy once had three different lovers within 24 hours. But she neglects to mention how she organized the logistics or what she did between sleeping with them. The main difficulty, however, was choosing between two high-powered literary critics: the gruff and rancorous Russian-Jewish Philip Rahy, who had dark lustrous eyes and “the look of a bambino in an Italian sacred painting,” and the pop-eyed, pink-skinned, short, stout, and breathy Edmund Wilson, who stole her away from the passive Rahy. The first time she went out with Wilson, whom she called the minotaur and savagely portrayed as Miles Murphy in A Charmed Life, McCarthy got very drunk, passed out, and woke up in a strange hotel room with every reason to fear the worst. But she found herself next to her companion of the previous evening, the vain and dumpy Margaret Marshall, literary editor of the Nation.

At their second meeting, though not sexually attracted to Wilson, McCarthy allowed him to make drunken love to her. Still unclear about what she wanted, she absurdly agreed to marry him, against her inclinations, as punishment for having gone to bed with him. Though the marriage was over just after the wedding night, she remained with Wilson for seven more years. It is astonishing that McCarthy’s penetrating, analytical mind had so little insight into the motives that influenced the crucial emotional decisions of her life.

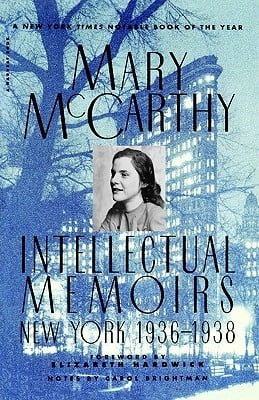

[Intellectual Memoirs: New York 1936-1938, by Mary McCarthy, foreword by Elizabeth Hardwick (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich) 114 pp., $15.95]

Leave a Reply