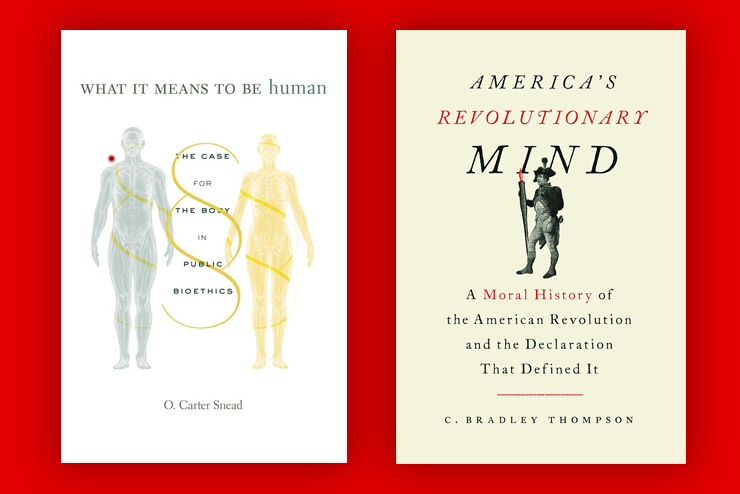

America’s Revolutionary Mind, by C. Bradley Thompson (Encounter Books; 584 pp., $32.99). Thompson’s examination of colonial America’s natural rights political culture and the effects of the Declaration’s oft-quoted passage about unalienable rights is not likely to please members of the traditional right, and as such I consider it required reading. Thompson presents copious evidence that those who led the American Revolution and established American governments afterwards embraced Lockean views about inborn individual rights.

Thompson demonstrates that early America’s prevalent understanding of Lockean rights stressed their universality. This belief in universal individual rights, according to Thompson, superseded the Declaration and the case made therein for American independence. Although Murray Rothbard, Thomas West, and Michael Zuckert have made similar arguments, Thompson’s thoroughness makes the best case. Those seeking to disprove his argument will have to do more than just repeat that Edmund Burke, not John Locke, was America’s true philosophical founder.

The antebellum South’s traditional way of life and social hierarchies resembled European feudalism more than the Lockean individualism Thompson focuses on. Historian M. E. Bradford remarked that Southerners living in a society of unequal members could not have understood “all men being born equally” as we do today. So why did Virginia’s planter class feel obliged to begin statements of political belief with an incantation they did not accept?

Constitutional historian Forrest McDonald noted the influence of ancient and modern Europeans, as well as the Bible, on early American political thinkers. McDonald argued early Americans eclectically constructed their regime around these multiple references. Still, natural rights skeptics ignore Thompson’s exhaustively researched scholarship at their peril.

(Paul Gottfried)

What It Means to Be Human, by O. Carter Snead (Harvard University Press; 336 pp., $39.95). This important new book tackles three “vital conflicts” whipping up today’s bioethics maelstrom: abortion, assisted reproduction, and end-of-life choices. Americans have wrestled with bioethics for over half a century. In 1965, Harvard professor Henry K. Beecher’s lecture to a science writers’ symposium uncovered more than a dozen medical experiments with neither therapeutic benefits nor, shockingly, the patients’ consent. Details of the U.S. Public Health Service’s decades-long exploitation of poor, syphilitic African-Americans in Tuskegee, Alabama horrified Americans in 1972. And just one year later The Washington Post reported on an NIH debate about funding European research on “newly-delivered human fetuses—products of abortion—before they die.” Do white coats smother the soul?

Sadly, smothered souls have ruled the debate since Beecher’s tocsin. Here Snead explains why. He argues that American law grounds itself in a pernicious view of man as “atomized [and] solitary,” whose ultimate worth hinges on his “capacity to formulate and pursue future plans of his own invention.” Such reductionism converts the world and the human body into tools solely dedicated to realizing one’s own will. So, if pregnancy interferes with your upcoming trip to Disney World, just remove the impediment. Or, as Justice Ginsburg alleged in her dissent in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, restrictions on abortion “center on a woman’s autonomy to determine her life’s course,” whether that course leads to decades of motherhood, or merely to an afternoon with Mickey.

Snead cites “expressive individualism” and its solipsistic drive for “one’s self-invented destiny,” first identified by sociologist Robert Bellah, as the theoretical culprit. Courts have used this egoistic perspective to rationalize sundry scientific enormities. Snead proposes we shift to an “anthropology of embodiment,” which discounts cognition and will, and instead reminds us “we experience the world around us as living bodies.” As such, humans surrender to natural limits imposed by death, senescence, and disability. Throughout life we rely on others in times of need, from infancy, to illness, to old age. Therefore we must act “without demand for or expectation of reciprocation.” Under Snead’s anthropology, all members of the human family—regardless of age, sex, cognitive ability, or the opinion of others—deserve care and protection. Remarkably, he makes his argument without invoking religion.

And therein lies a problem. While Snead lays out the history and philosophy of bioethics and applies his framework to each of the vital conflicts with great success, his solutions sputter. His general recommendation that the law “must be devised to secure the intrinsic dignity of children” will engender as much respect for the young as gun laws do for shooting victims. Our culture’s rot runs deep. The law can’t fix it; only cultural, moral, and religious change can. But credit to Snead for explaining the problem.

(John Greenville)

Leave a Reply