“If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth.”

—Psalm 137:6

This troubling memoir of James Dickey by his son, Christopher, is troubling as well for me to review because I knew James Dickey a little, and I greatly admire his work. Whether all the scenes in it are true or not—who of us really knew our father and mother—it is perhaps normal for an admirer to be defensive on his behalf Let me put more of my cards on the table: James Dickey blurbed two of my books, and my wife, Beverly Jarrett, has published two or three books about him and one by him (Striking In: The Early Notebooks of James Dickey), perhaps the last book published in his lifetime.

Before I had so much as heard of the memoir’s existence, someone called me to say the New York Times had nm a review (by the son of a former teacher of mine, incidentally) entitled “Liar and Son.” What the hell was going on? Dickey had always had literary enemies (poets are an especially cantankerous bunch at best, at worst vindictive churls), not a few of them in New York, and a presence as powerful as his was bound to challenge the impotent and the second rate, and even the first-rate. But this attack was by one of his own children.

There is no denying that Dickey drank too much and behaved sometimes outrageously. Many of us do. There is also little doubt that for children to witness their parents quarreling is a terrifying, traumatic experience. Christopher’s own son was spared this particular agony by his father’s early abandonment of the scene. Jim Dickey’s drinking was well documented long before the appearance of this memoir; thus I do not see how piling up stories of his drinking is useful in the pursuit of “truth.” Should one be interested in such stories, however, he will find a plentiful supply of them in this book.

Christopher makes much of Jim’s penchant for exaggeration, for creating other personae. Dickey himself had discussed what he was up to in “Barnstorming for Poetry.” He admitted he had a public persona and a private one—God help the person who does not. He admitted this was a problematic way to live, or to have to live. He exaggerated when he spoke about flying 100 missions in the Pacific: Although he had soloed and passed his final check (poorly, according to him), he ultimately became a radar intercept officer (according to Christopher) and flew, though not as a pilot,

thirty-eight combat sorties over thousands of miles of enemy territory and empty, hostile seas. He strafed, he bombed, he acted as bomber escort and provided cover for landing forces and convoy attacks. He was commissioned a lieutenant overseas, and got five bronze stars for offensives in the Philippines, China, Borneo, and Japan.

Goodness! How far from the truth the original was!

At one point in his memoir, Christopher Dickey remarks that “demythologizing was becoming my obsession.” He candidly admits his father passed on writing assignments to him that his father did not want to do, thus giving him a start in his current trade. Christopher tells about a commission from Life to write about the making of the movie Deliverance, a story that eventually was turned down for being “too negative.” Must have demythologized too much.

There is an undeclared assumption in a lot of expose journalism that merely by revealing the private, a purpose is served that is laudable and moral, to say nothing of financial. But even if, via the police state or “police journalism,” a camera were placed in every bedroom, every bathroom, when the camera is turned off and the fever of prurience has subsided, one still has the burden of meaning, of interpretation, to contend with. Any Jew or Roman walking on the road from Calvary could have given a passerby the details of the recent gory execution of three criminals, but what was the meaning of the event?

Christopher Dickey repeats the well known words of Monroe Spears to his father: When writing a poem, “no artist is bound by the truth.” Of course, between two intelligent and educated men, it was understood that “truth” used in this way meant a literal unfolding of the events that a poem might be based on, but that the poem itself could create another kind of “truth.” In discussing the poem “String,” Jim explained to his son that he had made up certain of the events. Christopher notes that his father then said, “But you’re a journalist. So the truth is important.” Christopher replies, “In journalism it is.” His father, he said, “considered that proposition for a time, as if waiting for more or better air.” What James Dickey might have been waiting for was his son’s acknowledgment that the “made-up” poem has its own important truth. From the context, however, the reader is not led to conclude that the memoirist understands this.

Interestingly, Christopher tells how his father did string tricks like Jacob’s Ladder for him when he was a child. Like most kids, the son wanted to know how it was “really done.” “Teach me to do it.” Jim agreed to show him, adding that “the secrets of this magic had to be kept just between us.” (If this were an opera, we would hear the basses and cellos presaging a dark final act.) On several occasions, the grown son still seems to miss the point of how poetry is made. Concerning the incident from which “The Bee”—where the father in the poem has to dash to save his son—was developed, Christopher remarks that his father just “took a couple of steps, reached out, and grabbed Kevin to keep him from backing into traffic. That was all that happened.” He seems to fault his father for not writing about the time in Italy when he “really had risked his life to save his son.”

Summer of Deliverance has some striking inconsistencies. Take, for example, this: “My father’s ideas of nature, for all that he wrote about it, were mostly imagined from movies safely watched in air conditioned theaters.” This is a real shot at the poet who wrote so deeply about the natural world. First off, the son was not born until his father was 28 years old, and what Jim did for the next five or six years would be mostly unknown to him, too. James Dickey’s father was a fox hunter, and there seems little doubt that his son knew something about rural Georgia. Later in the book, Jim takes Christopher camping, telling him “he had wanted to give me a little something of what his father had given him.” About this camping trip, Christopher feels compelled to say (I assume as an adult), “My father knew nothing about camping.” Later, about Jim’s archer)’ practice, he says, “He just preferred being in the woods.”

Only four pages later, Christopher is relating the canoe accident his father and his friends had.

They’d busted up the canoe in a stretch of rapids on the Coosawattee, a stretch of river they were noway ready for in a deep, narrow gorge, and AI, banged up badly on the rocks, almost drowned. The canoe had wedged up against him, filling with water, crushing him with the weight of the river. With all his strength and with all my father’s strength prying and pushing, he’d only just slipped free.

After this incident, which occurred in Georgia, the Dickeys moved to Oregon where Christopher says, “We still went camping together. . . . We’d drive deep into the mountain forests, which were so much bigger and wilder than anything we’d seen in the Appalachians. . . . Elk wandered in the woods near our camps, and bear were close by, too.” (An air conditioned theater?)

Such inconsistencies and contradictions occur throughout, and I have the feeling that Christopher Dickey, the adult author of this memoir, has not yet completed his journey of reconciliation. The book is very much the story of Christopher Dickey—maybe more, even, than that of his father, who lends it whatever interest it might have. Long-time students of James Dickey will not learn much that is new or essential for understanding Dickey’s art. They will learn something about one of his children, however. Here is a start: “My childhood was an adventure story, not a horror show. My father and mother had adored and spoiled me.” Christopher was an only child for seven years. He was read to often by his father. He writes about how Jim “wanted to share” the magic of the beach with Kevin, the younger son, and did.

The difficulty of providing for his family was not obvious to his sons, yet Dickey worked for an advertising agency during the lean years and worked long hours at night on his poetry. Christopher’s childhood was not haunted by talk of poverty, or the reality of it. When Jim made money, he sent his son to France to school, whereupon his son withdrew, came back to the States, and married when he was only 18 years old and had no visible means of support. His father, with the girl’s parents, provided for the young couple for five years. Dickey even bought his son a Jaguar XKE. None of this seemed enough, however. “I wanted to believe him when he said he admired me for whatever it was he claimed I’d done well. But every bit of praise was just that bit off target, as if he were talking about somebody else.” Nothing will satisfy the spoiled first-born.

There is, of course, a reconciliation at the end of the memoir. James Dickey is dying, and Christopher’s second wife (an Italian-American who understands family) urges her husband to see his father. In the midst of Jim’s terrible second marriage and his illness, Christopher, with his brother Kevin, steps in and helps put the house in order. There is no gainsaying this, nor do I wish to. His father needed help, as did his young half-sister Bronwen, and Christopher gave it.

This is a book, I think, that should never have been written. But it has been written and must be looked at for what it is, and not as a work of the imagination by which writers licitly transmute family experience into art. Christopher Dickey allows praise for his father, but somehow the words are undercut—taken away sometimes subtly, sometimes not so subtly. An opening sentence tells us, “My father was a great poet, a famous novelist, a powerful intellect, and a son of a bitch I hated.” Nothing subtle there. Later in the book, Christopher calls him a “cracker bard.” Part of this hatred comes from the way he says his father treated his mother. Fair enough. A son ought to defend his mother. And his father. Adultery is a cruel business, a betrayal. As he tries to come to terms with his father and mother, Christopher Dickey admits his mother could have left. After all, it was her second marriage. Christopher blames his mother’s drinking on his father’s drinking. But Maxine’s mother was a big drinker. The two women drank together.

For a tell-all exposé to carry authority, the writer must tell all he knows, unless what he really wants to do is an ax job disguised as praise. Christopher Dickey admits that he committed adultery himself while married to his first wife, drank excessively, and put his career ahead of his second marriage, staying overseas for months. Why didn’t he, to be fair, provide the sordid details of his own marital fights, the seamy specifics of his own adultery? Probably because they would embarrass him by making him look bad. He may have even wanted to protect members of his family, to be loyal to them.

On a car trip from Louisiana to Washington, D.C., in 1984, my wife and I stopped in Columbia, South Carolina, to visit with Jim. During dinner the first night, he mentioned that Christopher was in El Salvador as a journalist. I made an idle remark that, as far as the government was concerned, journalists and Catholic priests were considered the enemy down there. At first, misunderstanding what I had said, he thought I intended something negative about Christopher. Leaping to his son’s defense, he protested, as I recall, that he knew which side he was on and affirmed what he would do if the government dared to mess with his son. His fierce loyalty was touching. But Christopher would call this “an excuse for his overplayed emotions.”

The next morning at breakfast, which was to have been fixed by Jim’s second wife, Deborah, (who would not, however, emerge from the bedroom), Jim read his long, rhymed poem about Bronwen, his young daughter. This was the only time I ever saw her. She was quite a charmer at three or four, and I photographed her. Her father died when she was 15, and she wrote a one-page memorial to him in the March 24, 1997, issue of Newsweek that is precociously brilliant. It is hanging for all the writing students to see at the University of Arkansas.

Seeing him dying in the hospital, Bronwen broke into tears and thought:

Here was the man that changed my diapers, made me peanut-butter sandwiches (with the crusts cut off), showed me how to throw knives and to shoot a bow, read me poetry, stayed up with me all night when I was sick, taught me to play chess, came to all my recitals, braided my hair, watched movies with me, checked my homework.

She is left, she says, with memories of greatness, the greatness of a father. Bronwen concludes, using some of Jim’s favorite quotations,

I will live blindly and upon the hour. I will catch the dream in flight, though I do not know the color of the sky. And my father’s eyes, though they will not see my graduation, my marriage or my children, will always be somewhat strangely more than blue.

I must say I think Christopher’s much younger sister has written the better memoir, even if it is only a single page in length. Among Jim’s last words to Christopher were, “Remember what I was—to you.” Yes, indeed: remember. Even talk —among the family and close friends—about the bad times, if it seems necessary for you to do so. As for ridicule and attack, there will be strangers aplenty to volunteer for the job. Especially to “demythologize.” What we need more of are mythmakers to take the debris of the banal and commonplace and fashion stories to lift our eyes from the ground to the horizon, “to catch the dream in flight”—more people who understand the meanings of the myths.

If one is going to criticize one’s parents in public, one should have the courage to do so while they are alive to defend themselves. Otherwise, the secrets should be kept among the family as the magic itself is honored, by the confidants of blood.

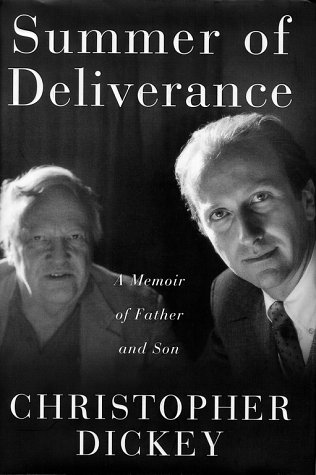

[Summer of Deliverance: A Memoir of Father and Son, by Christopher Dickey (New York: Simon & Schuster) 256 pp., $24.00]

Leave a Reply