One of the root problems facing our beleaguered world is that many of our contemporaries are belaboring the past as a burden, believing that the legacy and traditions of Western Civilization are a millstone around modernity’s neck. Cast off the shackles of the past, with its outmoded morality and outdated way of doing things, and we shall be free. Such is the credulity of what Evelyn Waugh called our “deplorable epoch.” The irony is that such unbelievable nonsense is believable only if we are ignorant of the lessons that the past teaches, an ignorance which is itself the consequence of believing that the past has no lessons to teach and contains nothing worth learning. Thus, it is intriguing that the West is seen metaphorically by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn as a millstone, as is clear from the title of these posthumously published sketches of his first years of exile there following his expulsion from the Soviet Union in 1974. It is perilous, however, to misread the metaphor. The millstone which the West represents is not the burdensome sort that hangs around the neck but the grinding sort that refines the meal into flour. Nor is it the “West” of Western Civilization but the “West” of 20th-century geopolitics. It’s not the West of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle; nor is it the Christian West, the West of the Church, the West of Christendom. It’s the West of Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, and Henry Kissinger; the secular West, the West of Wall Street, the West of the New York Times. The one West has nothing whatever to do with the other, except insofar as they are deadly enemies, and it’s crucial at the outset, if we are to understand Solzhenitsyn’s perspective, that the two Wests are never conflated. Solzhenitsyn is a friend and champion of the former and an indefatigable enemy of the latter.

Having oriented ourselves correctly we will see that the two metaphorical millstones between which Solzhenitsyn finds himself being ground are the Eastern millstone of Soviet communism and the Western millstone of secular liberalism. As for the book itself, it’s a gift for all those who admire Solzhenitsyn and especially those who recall the period that he sketches, enabling us to see his early years of exile, first in Switzerland and then in the United States, through his own eyes.

The Foreword by Daniel J. Mahoney, arguably the greatest living expert on Solzhenitsyn’s life and work, at least in the English-speaking world, raises with an appropriate degree of nous and gravitas the curtain on what follows, setting the scene and providing the context, as do the lines of the song that Solzhenitsyn selects as the epigraph to his sketches:

Thou distant land,

Land unknown to me,

Not of my own free will have I come to thee,

Nor was it my brave steed that brought me here:

What brought me here was misfortune.

These melancholic lines, the song of an exile in Pushkin’s novel The Captain’s Daughter, paint a picture, as only poetry can, reminding us, lest we forget, that the sketches of life in the pages that follow are drawn by an exile longing to return home. But the exile longs to return not to Soviet tyranny but to a renewed and revitalized Russia, liberated from the communist yoke, a Russia that had not yet emerged from under the rubble but which Solzhenitsyn, as a true prophet, knew was there beneath the surface, awaiting her resurrection.

Among the aspects of Between Two Millstones that will be of particular interest to European readers are Solzhenitsyn’s first impressions of Western Europe. Take, for instance, his description of Cologne:

We soon reached the train station . . . without my having seen much through the window, and hurried to the platform . . . getting there just two minutes before our train was to pull in. . . . But what two minutes! Right before me, in full view and in all its perfection, was that work of beauty, no, that miracle, the Cologne Cathedral! More than its intricate ornamentation, it was its spiritual depth that struck me, its towers and spires striving up to the heavens. I gasped, and stared with my mouth open, while the reporters, ever alert and already on the platform, took snapshots of me staring. And then the train pulled in and swallowed us up.

These are not the words of the modern iconoclast who bewails our Western heritage as a millstone around our necks! Solzhenitsyn confesses to having a fondness for Germany, which he attributes to his enjoyment of studying German and his learning of German poems by heart, and to his reading of books of German folklore, as well as The Song of the Nibelungs, Schiller, and Goethe. He was, however, disappointed by his first impressions of the Rhine, which “seemed dirty and industrialized, no longer poetic.” Even the Lorelei Rock, which was pointed out to him, had been spoiled, sullying his romantic vision of its timeless charm. “It must have been idyllic before it had been spoiled in this way. But the main beauty of the area, the centuries-old huddling houses and narrow streets, could not be seen from a passing train.”

Finding himself homeless and searching for a suitable place to settle with his family, he thought that Norway might prove to be a sort of home away from home, or at least a place that might remind them of home even if it could never be a substitute for it. Its “wintry northern land, long nights, [and] wood throughout the home” eased his exiled heart, and in the works of Ibsen and Grieg he detected “a certain similarity with the Russian character and everyday Russian life.” Had he been familiar with the works of Sigrid Undset, that greatest of Norwegian writers, he would have felt there a kindred spirit beyond the faint echoes to be found in the dour northernness of Ibsen.

Much of Between Two Millstones is the venting of Solzhenitsyn’s spleen against the Western media, which is not surprising considering the scandalous way in which he was treated at their hands. Take, for instance, this riposte against the New York Times for suggesting that he was “not a democrat”:

And yet I am much more of a democrat than the New York intellectual elite . . . [I]n my view, democracy means the genuine self-government of the people, from the bottom up, while these people see it as being the rule of the educated classes.

Here we find an allusion to the political philosophy that Solzhenitsyn would articulate brilliantly in Rebuilding Russia, a vision of society rooted in the principles of subsidiarity and solidarity that harmonizes with Western thinkers such as E.F. Schumacher, G.K. Chesterton, and Hilaire Belloc, and which dovetails with the Catholic social teaching to be found in papal encyclicals by successive popes, from Leo XIII and Pius XI to John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

Much more could and should be said. There are descriptions of Solzhenitsyn’s attendance at Russian Orthodox services, resonant with images of worshipping in the catacombs; there are his views on nuclear weapons which the present writer believes to be naive and wrongheaded; we read further of his much-publicized falling out with fellow dissident Andrei Sakharov; his fear for the safety of his children; his stumbling upon the grave of Rilke; his pilgrimage to Shakespeare’s Verona; his sickened astonishment at the profusion of communist graffiti in Italy (“A dose of the real thing might have opened these people’s eyes”); his admiration for the Swiss model of democracy; his views on tensions between Russia and Ukraine; his disdain for neoconservative Russophobia; his disgust at the ugliness of New York City; his experience on Meet the Press; and, most welcome of all, his response to the fallout of his Harvard Address.

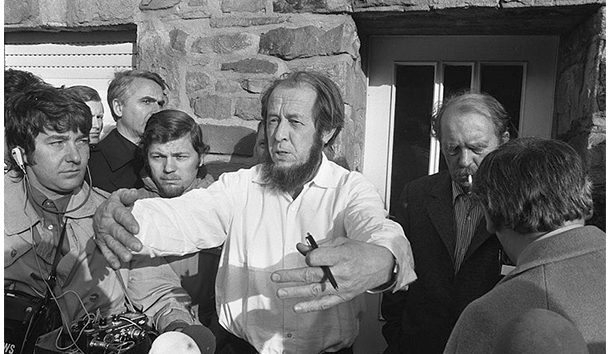

If there’s one negative dimension to the book it’s the pervasive tone of po-faced self-justification. For those who do not know Solzhenitsyn, such a tone might appear arrogant or pompous, though it must be said that his pomp is never without circumstance. What is missing is the human side. Instead of the public persona of the prophet and man of letters, it would have been good to see the sense of humor and the humane warmth that I witnessed when interviewing him in Moscow in 1998. The mischievous glint in the deceptively boisterous China-blue eyes; the infectious chuckle. The serenity. Dare one even suggest, the sanctity? It is true that the Solzhenitsyn of 1998, four years after his return to Russia after twenty years of exile, was much mellower than the Solzhenitsyn of two decades earlier, the warrior in the heat of the fray whose sketches these are. Perhaps, one day, his own family, his wife and three sons, might collaborate on a memoir that will reveal the private man, the father and the husband. Until such time we must be grateful for these sketches and the insight into the times that they offer, as well as the all-too-rare and occasional glimpses of the lovable man behind the publicly impenetrable mask.

[Between Two Millstones, Book 1: Sketches of Exile, 1974-1978, by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (University of Notre Dame Press) 480 pp., $35.00]

Leave a Reply