Patricia Highsmith is a peculiar taste, nasty and unpalatable to many. Readers who like her, however, tend to like her enormously. She was born in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1921, the unwanted daughter of a graphic artist who attempted to abort her by drinking turpentine. Her father left home before she was born, and she moved with her mother and stepfather to New York at age eight. In due course, she graduated from Bar-nard College and took jobs that included writing the storylines to the Superman comics.

Highsmith’s big break came in 1951 with the publication of Strangers on a Train. Alfred Hitchcock, in need of a good story to bolster his credibility with the Hollywood studios, bought the film rights for $2,000. The author was disappointed, but Hitchcock assured her that this would be the making of her career. Certainly, it meant the revival of his.

Hitchcock reshaped the story to conform to Hollywood sensibilities, and the usual innocent-man-on-the-run story ends happily with the death of the criminal. Similar liberties were taken with both film versions of The Talented Mr. Ripley, the stylish French version Plein Soleil and the even more unsatisfactory Matt Damon vehicle of 1999. Again, neither France nor Hollywood, even at this late date, could let the eponymous hero get away with murder.

Such tampering misses Highsmith’s vision entirely. As in life, murder in her world, more often than not, is never solved, nor are her malefactors brought to justice. Indeed, justice itself, when it appears, is a happenstance phenomenon. Highsmith cut slack only to animals. Something of a misanthrope but a devoted cat owner, she wrote a series of stories collected in The Animal-Lover’s Book of Beastly Murder, which makes up the first of the collections in this volume. The common theme is that of various members of the animal world taking their revenge on cruel owners or mankind in general. These are the only truly predictable stories in her work—she apparently could not bear to let the dumb chums get the short end of the stick.

Highsmith had no such qualms about members of her own human sex. In the second collection in this volume, Little Tales of Misogyny, we get short portraits of various types of women, chiefly 20th-century middle-class American, some sympathetic, most appalling; among them the 12-year-old who, encouraged by her mother, dresses like a trollop and finds some pleasure in complaining about the commotion she can cause. More than once, the price is rape, but she finds satisfaction in the punishment the law metes out to her own pathetic Humbert Humbert. Coquettes, conniving wives, wives distracted by serial enthusiasms, and the men who lose all in pursuit of them make up the bulk of this decidedly “politically incorrect” work.

Consider the “The Mobile-Bed Object”:

There are lots of girls like Mildred, homeless, yet never without a roof—most of the time the ceiling of a hotel room, sometimes that of a bachelor digs, of a yacht’s cabin if they’re lucky, a tent of a caravan.

For five pages, we follow Mildred’s short, disgusting, fitfully satisfying life until she is murdered quite matter-of-factly by her last squire and immediately forgotten by those few people who knew her. There is genuine mischief in this volume, stuff that might have given pause even to Dorothy Parker or Claire Booth Luce.

The first two books are thematically unified, even gimmicky. The final three (Slowly, Slowly the Wind; The Black House; and Mermaids on the Golf Course) are generally straightforward stories. As with Mildred, chance encounters with violence or even chance escapes mark the lives of Highsmith’s characters, set the small dramas on their way, or finish them abruptly. The optimistic American view that you can do or be anything you want to is scotched firmly and often in Highsmith’s universe. Those who try to manipulate affairs to satisfy their preferences tend to find that life is indeed haphazard.

Thus, in “The Baby Spoon,” we meet Claud Lamm, professor of literature and poetry at Columbia. Married to a nice but unsophisticated woman who irritates his soul, he finds cruel satisfaction in her loss of a keepsake spoon, apparently to the petty thievery of his most promising ex-student, now a starving poet who hits him up for sympathy and money. In time, however, he finds the loss of the spoon works changes in his wife, breaks her out of her childishness, even makes her into someone of whom he can actually be fond. Imagining that others are playing out roles in his own mental drama and for once wanting to share his understanding, he tips a wink to the thief, thanking him for his action. The poet—possibly innocent, certainly overwrought

—is offended at the suggestion and, instead of acknowledging his part in the affair, turns violent.

There are flashes of other writers and other stories, chiefly those sharing Highsmith’s jaundiced view of life. Evelyn Waugh’s watchful Pekinese in “On Guard” finds its more self-concerned counterpart in a Siamese cat in “Ming’s Biggest Prey”; his gentle lunatic strangler in “Mr Loveday’s Little Outing” gains a less laughable counterpart in “The Button.”

Not only is Highsmith deadpan, she is free of sentimentality. Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” that hopelessly obvious chestnut, gets its workover in “Not One of Us.” “It wasn’t merely that Edmund Quasthoff had stopped smoking and almost stopped drinking that made him different, slightly goody-goody and therefore vaguely unlikable. It was something else. What?”

What indeed? Certainly Quasthoff is a bore; beyond that, he is the kind of person who somehow makes your claws extend. It does not take much to make a group of Upper East Side sophisticates conspire to mistreat this weakest link in their circle so cruelly as to inspire suicide. Patricia Highsmith cuts a little closer to the bone than Shirley Jackson. Straight delivery triumphs over message or jokiness every time, and you quickly begin to see why she is not for everyone.

And so it should come as no surprise that, once she had hit her stride, Patricia Highsmith found more awards and far better sales in Europe than she did in America. Indeed, Little Tales of Misogyny was first published in German translation as Kleine Geschichten fur Weiberfeinde. The affection Europe felt for her was mutual, and after 1963, she spent the bulk of her life living and working alone in France, England, and Switzerland, where she died in Locarno in 1995.

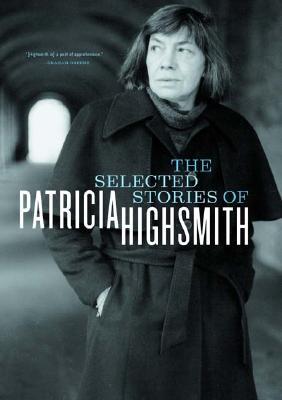

[The Selected Stories of Patricia Highsmith, by Patricia Highsmith (New York: W.W. Norton & Co.) 672 pp., $27.95]

Leave a Reply