According to a recent Roper poll, only 13 percent of the college graduating class of ’96 could pass a simple quiz on material suitable for elementary school students. Ninety-two percent of those taking this quiz failed to identify the author or the document that is the source of the phrase, “Government of the people, by the people, for the people.”

At his “Million Man March,” Louis Farrakhan claimed he was beamed up to a spaceship where he was provided with insights about life on earth.

A leading environmentalist said if the Amazon rain forest is destroyed there will be no oxygen left on earth, even though 98 percent of the oxygen is produced at sea.

A Senate committee on agriculture asked Jane Fonda, Jessica Lange, and Sissy Spacek to testify because they had appeared in films about farmers.

These items are not offered as definitive proof of social depreciation, but as the authors of the essays in Dumbing Down well realize, they are testimony to the direction we are headed. While this book does not identify a single culprit for our cultural decline, speculations on the passing of civility, on anti-elitism, undifferentiated educational standards, and slovenly speech point to radical egalitarianism as the primary villain. In a remarkable turn of events, equal opportunity has been transmogrified into equality of result, and equality before the law has been translated into equality of guilt and innocence. In no institution are these conditions more demonstrable than our schools, where, as Heather MacDonald explains, teachers of English composition emphasize the cultivation of “self esteem over competence and of self expression over the discipline of syntax.” Gilbert T. Sewall writes movingly of the insinuation of relativism into every crevice of basic education.

This American disease of the spirit is not entirely surprising. As George Kennan points out, Alexis de Tocqueville argued in the 19th century that excellence would be the casualty of advancing egalitarianism. It is now taken for granted that elitism is a pejorative, a sign of having lost touch with the common man. Mass culture is the instrument of egalitarianism, turning everything in its path into homogenized pabulum digestible by all people, satisfying to all tastes. High culture has been crucified on the cross of democratization.

While the essays in this book are uniformly lively, and some of them are exceptionally good—such as Cynthia Ozick’s “The Question of Our Speech: The Return to Aural Culture” and Armstrong Williams’ “I Feel Good to be a Black Male”—several suffer from misplacement and others from questionable judgment. John Simon, for example, challenges Joseph Epstein’s argument for discontinuing the National Endowment for the Arts by noting, “Any support, even to the wrong artists, is better than none; at least it stirs up controversy, and makes an inert public more aware that the arts exist and matter.” Really? I prefer to buy my own tickets rather than have some government bureaucrat tell me how tax dollars should be spent on the arts. Sven Birkerts criticizes the Internet as a virtual world cut off from reality, atomizing relationships and the natural rhythms of life. Here again, my own experience is different. Without exaggerating the importance of the Net, which houses as much trash as archival emeralds, a communications instrument touching millions of lives could be accessible in every home to break the communications monopoly that once impeded the free exchange of opinion.

David Klinghoffer offers a persuasive argument against kitsch religion—religion that is so secularized it regards New York Times editorials as more spiritual than the Bible or the Torah. But if mainline Protestant religions and Reformed Jews are losing congregants to orthodox faiths, as is the case, this trend would seem to run counter to the book’s thesis. Similarly, Carole Rifkind’s piece on “America’s Fantasy Urbanism: The Waxing of the Mall and the Waning of Civility” conflates a diminished sense of citizenship with private and commercial values. 1 would make almost exactly the opposite point: private property is continually encroached on by the spread of public space, usually under the banner of environmentalism, thereby challenging the traditional nature of citizenship. And I am startled to read the claim that “eating out is normally not at its best in America today.” Nahum Waxman, who makes this point, must be living in another country. Sure McDonald’s and Burger King are nothing to brag about, but in my judgment there are more fine restaurants, more gourmet treats available in modern America than was ever the case anywhere in history.

My difference of opinion with several essays has not diminished my heartfelt appreciation for a book that tackles America’s “dirty secret” directly. As someone who has taught in the academy for three decades, 1 am well aware of the social signs that bear testimony to a diminishing sense of genuine accomplishment. In far too many academic quarters, ideology has replaced critical judgment and democratization of the spirit has undermined good breeding and character. My ears are sensitive to the sound of student grunts and “ya know,” and I long for the day when language will be the inspiration for uplifting ideas. But that is not a day I will soon see. The inertial force of Dumbing Down is an avalanche that will not retreat on its own. All one can do is avert one’s gaze, dream of noble moments, and hope for the best.

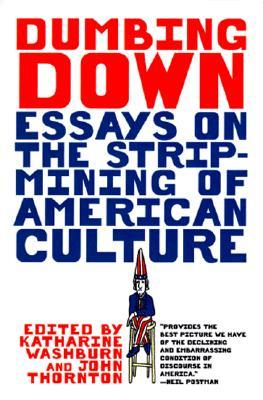

[Dumbing Down: Essays on the Strip-Mining of American Culture, Edited by Katharine Washburn and John Thornton (New York: Norton) 329 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply