It is June 1994, and Anthony Hilder is attending a Southern California gathering called “The New World Order.” Two overhead projectors beam book-covers alleging Masonic conspiracies onto the walls. Hilder, white and middle-aged, is the host of two syndicated talk-radio shows, Radio Free America and Radio Free World. He has brought tapes to sell to other attendees, and is doing a brisk business; quite a few people have wandered through the smoke-filled room to peruse and purchase his wares.

Many might assume Hilder and his customers to be racists. They will be surprised to discover that the event was a multiracial rap/rock concert in downtown Los Angeles, featuring Ice T, Body Count, Fishbone, and Ice Cube, among others; that the gathering was organized not by a white man donned in camouflage, but by a black record producer who calls himself Afrika Islam; that the smoke thickening the air was not burning tobacco, but burning marijuana.

The popular stereotype of the militia movement does not leave much room for cultural diversity. The media have had to acknowledge one prominent African-American militiaman—James Johnson of inner-city Columbus, Ohio—if only because of his high profile in the movement. But he is treated as an aberration—or, worse vet, a token. More common are hysterical quotations from representatives of the Anti-Defamation League and the Southern Poverty Law Center, both of which have accused the militia movement of fomenting bigotry. Their evidence is about as solid as J. Edgar Hoover’s was for claiming the civil rights movement was controlled by communists: a handful of offenders on the edges of the insurgency, whose association is considered enough to presume everyone else’s guilt. Bob Fletcher, a former leader of the Militia of Montana, sums up the situation by reversing Sturgeon’s Law: “About 10 percent of America is racist, and I suppose that’s true of the militias, too. You get that in any organization.” Once you ignore this small klatch of Christian Identity bigots, the case for militia racism dries up. Though predominantly white and Christian, militia groups include blacks, Hispanics, and Asians; nonbelievers, Muslims, and Jews.

But what happened in Los Angeles in June ’94 went beyond this. The New World Order party was not in any sense a militia meeting—indeed, organizer Islam says he does not “really have an opinion” about the movement. The concert was a sign that men and women far removed from the militia milieu not only share the patriots’ basic concerns—a fear of state repression, a populist demand for self-government—but are recognizing that these “right-wingers” may be kindred spirits, political labels be damned. After all, blacks and white radicals have similar reasons for distrusting the state. Both fear the government’s increasing police powers. Both resent the abuses of civil liberties that have come with the war on drugs, and both accuse government officials of being involved with the drug trade themselves. The firebombing of MOVE and the beating of Rodney King catalyzed the same resentment among blacks that the Ruby Ridge standoff prompted among many whites.

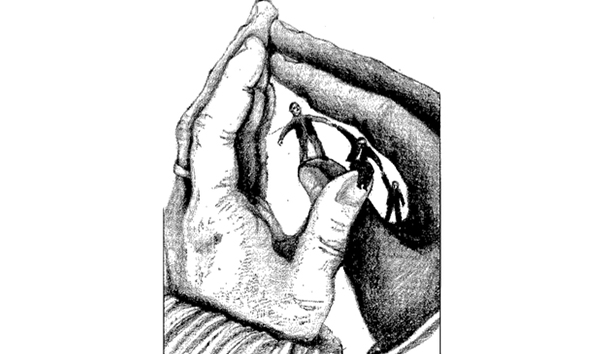

The Waco holocaust brought the message home. Almost half the Branch Davidians killed at Mount Carmel were minorities—28 blacks, six Hispanics, and five Asians. So there was a good reason for militants of different races to start cooperating: more and more, they seemed to be fighting the same fight. As Fletcher put it, “As things get worse, blacks and whites will be thrown into the same trash-pail.” To avoid that fate, the black nationalist and militia movements began to fuse along their edges. As of yet, no media have covered this story. Tacking it down meant following a labyrinthine phone tree, and often calling people who were at first too suspicious to talk. Consequently, it is hard to say just how widespread the crossover is. It is clear, though, that the intersection is real and growing.

Two organizations figure prominently in the tale: Zulu Nation and the Nation of Islam. Zulu Nation was born in the early days of hip hop. Afrika Bambaataa has been a DJ and community organizer in New York City since the 1970’s; along with Grandmaster Flash, Cool Here, and others, he was one of the founding fathers of rap. Zulu Nation was his creation. Meant as an alternative to gangs, the group invited ghetto youth to concentrate on rapping, breakdancing, and graffiti, and not on criminal violence. Today, the Zulu Nation includes musicians, filmmakers, and others around the world—a quarter-million, claims Islam, himself a member. One of the “primary functions of getting in,” he adds, is sharing and spreading interest in theories about the New World Order.

In 1994, Islam’s friend Hilder appeared on The Front Page, a popular talk show on KJLH, a black-oriented radio station in Los Angeles owned by Stevie Wonder. There, Hilder mixed the conspiracy theories popular in the militia movement with appeals specifically targeted to a black community ruptured by unemployment and crime. One listener who tuned in that day was Rasul Al-Ikhlas, host of The Story of Soul, a wide-ranging public-access television program. Al-Ikhlas invited Hilder onto his show—and, at his guest’s suggestion, had Fletcher come along as well.

News of the newcomers traveled fast, thanks largely to the Zulu Nation network. Hilder’s black girlfriend had the amusing experience of visiting a village in Belize, only to be recognized by a native who had heard a tape of her speaking on the radio. Soon, Islam introduced Hilder to Michael Moor, a reporter for the Nation of Islam’s newspaper, The Final Call, and shortly afterward Moor appeared on Hilder’s radio show. There they argued that the powers-that-be are driving America toward a race war, and that men and women of all ethnicities should work together to defuse the battle before it starts. Other Muslims, such as Cedric Welch of The Final Call, also began to show an interest in the militia/patriot worldview.

Many readers, learning that elements of the militia and Black Muslim communities have begun to cooperate, will assume that the common ground is bigotry. Both groups, after all, have been plagued by accusations of anti-Semitism. There is indeed anti-Jewish sentiment among many Black Muslims—Hilder recounts an unpleasant confrontation with the infamous Khallid Mohammed, whom he describes as a “crazy” who wants to kill all whites, especially the Jewish ones— but it does not play much of a role, if any, in the black-white crossover. “The blacks that are anti-Semitic won’t have anything to do with me,” Hilder explains, “because they’re also anti-white.” (Hilder did once share a microphone with Steve Cokely, a black militant I have witnessed citing The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and casually using the word “Jewboy,” but the pairing didn’t work out: after the program, Hilder was snubbed by Cokely and his companions because of his race.) As for the other side of the equation, Fletcher’s wife is part Jewish and Hilder, though a Christian, is a former member of the Jewish Defense League. The patriot movement as a whole includes many Jews, including half the directorship of the San Diego Militia.

More troublesome is the extent to which the new overlap is based not on a common political agenda but on dubious conspiracy theories. Hilder and company’s power analysis, alas, owes more to Gary Allen than to C. Wright Mills. It is one thing to expose corruption in high places, or the growing power of executive agencies, or the rapidly globalizing corporate state. It is quite another matter to assert that a single cabal of Illuminati stands behind it all. Even leaving credibility-of-evidence issues aside, the sheer resilience of the power elite indicates that such a conspiracy could not be true, for much the same reason that centrally planned economies fail while freemarket systems succeed.

But below the surface one finds a concern with issues more concrete than the quest for a Grand Unified Conspiracy Theory. As Mack Tanner put it in Reason magazine, people “aren’t seared because they believe in conspiracy theories. They believe conspiracy theories because they’re scared.” The militiamen want to preserve gun rights, free speech, national sovereignty, and privacy, and to prevent any more incidents like Waco or Ruby Ridge. Those may not be the black militants’ chief concerns, but that does not mean they disagree with the militias’ agenda. Al-Ikhlas says, “I don’t like guns, period,” but then adds that he supports the Second Amendment. Islam agrees that gun control is not an essential issue, but he believes that guns represent power and control, and that this is why the state wants to seize them. For their part, the blacks are mostly concerned with local issues—Al-Ikhlas, for example, is now involved in an effort to turn an empty, government-owned building over to a volunteer drug treatment program.

And behind both the conspiracy talk and the single-issue concerns, there is common political ground. The militiamen want to make America a decentralized, constitutional republic; the black nationalists are calling for neighborhood power—which, in practice, is pretty much the same thing. “I would like the government, the police and councilmen, to live right here in the community,” concludes Al-lkhlas. Moor goes further, striking an almost Tolstoyan note: “If we’re all following and submitting to the will of God . . . then you don’t need government.” Hilder, a philosophical anarchist, is quick to agree.

This is not to say that any of this will last. Moor, for one, has cooled to the idea of black-white cooperation. When I called him to discuss this story, he was unenthusiastic. “I don’t talk to the white media no more,” he told me gruffly. “Every time we talk to Whitey, something happens.” The militias “seem sincere,” he continued, “but you have to wonder what their hidden agenda is, who’s pulling their strings.” There’s always the chance that “behind closed doors, we’re still niggers to them. I’m not necessarily talking about Anthony [Hilder], but sometimes I don’t even know where he’s coming from.” After all, “They’re getting too much pub’ from the white media. . . . After they overthrow the overlords, maybe they’ll start lording it over people of color.”

Al-Ikhlas—a black and a Muslim, but not a Black Muslim—remains tolerant, but even he has his doubts. “When militia people talk about ‘the good old days,’ I want to ask them, ‘How far does the militia want to go back?'” Despite this, he rejects the popular image of a movement dominated by white supremacists. “The media portray it differently than what it really is,” he says.

The alliance that remains is determined to stick it out, and to propagate its message as far as it can. Islam has been busy producing an album on Warner Brothers for a rap/rock supergroup called the Bubbleheads, a CD he promises will include a trove of conspiracy lore. In the meantime, Hilder has recorded a rap of his own, a catchy number called “Ordo Ab Chao.” And if the vision it expresses seems a little, er, apocalyptic . . .

Masonic mind manipulation

Inciting riots, it’s crisis creation

Biochip implantation

Vaccinate your kid for U.N. identification

. . . the wake-up message behind the X-Files motifs is still loud and clear:

They’ve numbed us down and dumbed us down

With TV, drugs, the NEA, and public schools.

They’ve taken your brightest and our best

And made them public fools.

Cast the tired old labels aside. From here on out, things only get stranger.

Leave a Reply