On the morning of July 13, 1985, as I noted in my journal, I woke with an exceptionally clear recollection of a dream. In it my wife, Elizabeth, and I were in a high-ceilinged Victorian room with brown walls fashioned of rotating metallic discs. From there, we moved outside onto New York City’s Park Avenue, where a group of elderly men were gathered for what seemed to be a parade. However, in a minute, most of them moved away. Elizabeth and I remained there, atop a steep hill, looking down on 34th Street and other city streets below. Up the hill (was it Murray Hill, which I remembered from a visit to the old Murray Hill Hotel in 1946?) marched a company of soldiers in World War I uniforms. They wore bright green sashes across their chests in the manner of certain Civil War regiments. We had a panoramic view of what appeared to be the old Pennsylvania Railroad Station, which I was familiar with in my youth. The railroad station and the cityscape were bathed in an eerie green light. There was snow on the ground.

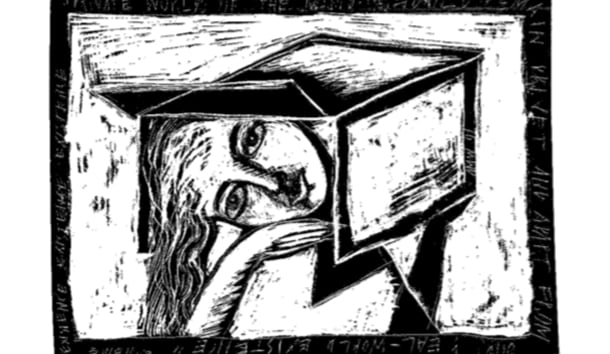

This is one type of private world—a fantasy world—that everyone knows at one time or another. From birth to death, we are constantly shaping and reshaping our visions of the world, creating worlds inside our heads. We do this even as we proceed with our normal daily activities, in a purposeful fashioning of an overall image of the various worlds that confront us or impinge on us, in daydreams and reveries, in dreams at night and in memory.

Loren Eiseley describes the power behind the cosmos this way: “It makes in fact all of the innumerable and private worlds which exist in the minds of men.” All too often we ignore these private worlds, which all of us know, and think only of the shared public world. The real world is always with us, to be sure, but it is subjected to private interpretation and conceptualization. Indeed, the real world is different for everyone. Consider the world of human relationships. They can’t be fully described in any objective way apart from the observer. The relationship of parent to child, child to parent, family members each to the other, friends to friends, and stranger to stranger are rarely identical. The individual sees every other human being in a special context; each individual exists in his and others’ frameworks of relationships or, in some cases, becomes virtually invisible. Relationships aren’t necessarily reciprocal or equal.

One of the strangest capacities of the human being is his ability in dreams to put real people in situations that are fictional, utilizing their known characters while giving them applications that have nothing to do with their real lives, as in the case of a dream I had that involved two good friends from different parts of the country and different social worlds. It was an intelligence-caper type situation in Nazi-occupied Europe. Pondering this sort of thing, one is bound to ask: what led to this peculiar dream scenario, which had nothing to do with the real life experiences of the individuals involved, even though they looked and acted in ways that were generally true to life?

In considering dreams and reveries, one realizes that our private amnesias are never permanent or complete, that nothing is truly lost to the human mind, though it is often difficult to access the distant past or even recent experience. Every minute of every hour of every year is stoked with impressions of people and things, places, nature, spiritual and intellectual experience. Every datum, every thought or fleeting impression is stored in the brain and available for use as a block to build a private world. Of course, the greater part of the material in the library of the mind is never used.

As I noted in my journal for a February day in 1979, I once again experienced a special world’ while taking a mid-morning walk on the beach near my home on Kiawah Island in South Carolina. A strong wind was blowing across the strand, but I was warm, as I was wearing a Navy aviator’s coat with a thick lining and a fur collar. It was a marvelous, sunlit winter day. I had the beach to myself, except for the shore birds. I sat down on the cold sand along the duneline, relishing the quiet, the natural beauty, and the soothing isolation. I took off my shoes and socks, rolled up my trousers, and walked in the gullies and the edge of the surf. The icy water produced a pleasant tingling sensation. It was a perfect day, no past and no future. It was as though time had stopped and I was alone in the world. Yet I didn’t feel lonely or in need of anyone or anything. That may be what it feels like when one transcends time—in eternity. The perfection of the world was all around me; it was completely undisturbed. I was beyond worry, discomfort, or disturbance.

The Kiawah experience belonged to a different type of private world. It was evidence of a real-life experience of living on an island and of my fondness for that type of quiet, isolated existence. The Kiawah experience also had in it an echo of my liking for a truly remarkable American book, The Outermost House, which tells of a year spent in an old cottage on Cape Cod in the 1920’s, long before there was any crowding or spoilation on the Cape.

Not all these worlds are painless; for example, our childhoods may have been painful experiences, and revisiting these worlds can be traumatic. But there are also youthful, private worlds that have a mixed character, worlds in which sadness and happiness are in equilibrium, as when I recall the private worlds of my summers in the half-dozen years after my father’s death—the early morning ritual of opening the stained glass front door of my family’s old house on Schroon Lake in New York’s Adirondack Mountains, and walking out on the porch to sit on the front steps next to geranium-filled flower boxes and to watch the sun playing on the waves a hundred feet in front of the house; it was a private world of stillness and profound peace. On those mornings I was keenly aware of my personal loss. Next to me was the outline of a large fish that my late father had cut into the floorboards, a sign of the presence that had been removed from us. Those peaceful mornings helped me tolerate my loss and accept an emptied world to a degree sufficient for me to function.

The relationships of childhood often fix in our minds and form the basic structure of our lives. Until my father’s death, my world was totally secure. I never heard an angry word in the home in which I grew up, and love and unity characterized my family. It was an extended family in the sense that our servants—immigrants from Scotland, Sweden, Germany, Switzerland, and Slovakia—were integral parts of the family and, hence, of my world. To this day I think of them and pray for them each day. Of course, whereas my childhood world was secure, it was not entirely so for the servants in my parents’ employ. Though treated with consideration, they were subject to economic uncertainty. My sister’s nurse, Louise, who sought to keep my sister an infant, had to leave when her methods became intolerable, though we kept in touch with her for the rest of her life. My Scottish nurse, Maggie, had to seek another position when it came time for me to have a governess. Our chauffeur, Anderson, returned to Sweden when my father’s death and the onset of the Depression made it impossible for us to employ a chauffeur or even keep a car. All this means that my private world of childhood did not correspond completely with the private worlds of the servants in my family.

As one grows, one’s private worlds multiply and become more extensive. Every year, every new place, every evolving network of relationships—school, college, young adulthood, marriage, parenthood and even grandparenthood—opens new private worlds of the mind. In this context, older private worlds may be reshaped to be made consistent with the experience of maturity. But one still never loses touch with the private worlds of yesteryear. One may enter them at any time and recapture their existential quality and even come to realize that there are many mansions in the house of time. And it is even possible to focus on a single private world, one niche in time, while largely ignoring the contemporary public world.

Both dreams and serious thought about different modes and forms of existence, such as the reverie on the winter beach, are reminders of the potential of human existence. Time prevents us from following all of life’s paths, but imagination can take us where we otherwise could not go. Private worlds of the mind suggest new and untried avenues; they establish and impose unanticipated new networks on our daily existence. If we understood this better, we would appreciate the fact that we live in and with a field of relationships—with family, friends, work associates, and strangers, all of whom are part of our personal landscape. Each figure in this landscape has his own landscape that relates to but isn’t necessarily part of ours, and the points of reference on his landscape are different.

Our access to private worlds enables us to transcend time to an important degree. Even as one approaches old age, it is possible to experience the zest and excitement of thirty years past, and to see one’s friends as they were in earlier decades. Thus the pleasurable world of the mid-to-late 1950’s comes alive for me as I remember such things as the parties given by my friend McColl Pringle in his family’s old house on South Battery in Charleston, in 1957. I can envision the crowds of friends who danced in the ballroom, the color of the girls’ evening dresses, and the sound of rock-and-roll in its first phase—songs such as “Behind the Green Door,” to which I danced with my wife.

This recollection—this private world—is much more than a fleeting memory. I recall the whole world in association with a period and a group of friends. The dances that I see with my mind’s eye, the feeling of being transported into a vanished era, are part of a world that exists in rich detail and variety—parties on Louis Green’s yacht in Charleston Harbor, a day at Billy Coleman’s country place on Wadmalaw Island, Sunday afternoon gatherings at Bob and Mary Hagerty’s Sullivan Island place with its antique private railroad car under a shed, an evening harbor trip in Aussie Smythe’s Boston whaler. This seemingly lost world isn’t lost at all—it can be retrieved and relived as a private world of the mind.

The smallest, most remote causal connection can open the mind to a private world often submerged under the exigencies of the real-life public world. The retrieval is occasioned by a bar of music, a taste of food or drink, a line in a book—the number of keys is myriad. One may recognize such keys as music associated with certain events or people, but the mind is full of many types of keys. One cannot begin to fathom the complexity of the trigger mechanism that prompts thoughts, recollections, and mental constructions. David Plante, writing of such triggers in an article in the New Yorker, has said, “I am drawn to objects of history. I love having on my desk, on shelves, in drawers so that I come across them unexpectedly, the handle of an amphora, a rusty key, a shell casing—stilled moments but moments that if they were put into motion by proper study would expand into years, decades, centuries.” In other words, these objects unlock his private worlds.

We can create private worlds in a vast number of areas. We can bring alive in our mind the world of Stonehenge, of the Great Depression, the Italian Renaissance, or the antebellum American South. Obviously, the knowledge we acquire in life, our reading and historical speculation, helps us to develop a transcendence that is manifested in the acquisition of extraordinary private worlds. But even the man or woman with little knowledge of other historical eras and types of human existence can open private worlds that he or she has a lifetime to explore.

Great writers are explorers of the private universe. One thinks of Henry Thoreau at Walden Pond. His time in that isolated spot enabled him to develop his unique perspective and idiom. From ancient times to the modern era—from St. Augustine to Santayana—there have been writers who discover new worlds to explore in the human mind. In reading them, we realize that there is much more to reality than the utilitarian comprehends. Indeed, as we penetrate the inner life of the mind, we may conclude that knowledge of private worlds is one of the greatest discoveries in life, as when we encounter writers who truly wake us to another dimension of meaning. Stephen Jay Gould once said of listening to a great German scholar, “I sat spellbound as wave after wave of expanded meaning cascaded over me.” James Webb, the novelist and former Navy secretary, reminds us that the duty of a writer is “to study human nature, to study the human condition.” He says that “The orientation for introspection is the chief benefit for writing.”

Painters as well as writers create and explore private worlds of the mind, no one more so than Hieronymus Bosch. The 16th-century master compels attention today, as he did in his own time, with his bizarre and terrifying masterpieces. His chilling visions are of demons, monsters, and unspeakable cruelties. His world is a world of horrible punishments. This vision was drawn from medieval folklore, with the rat as a symbol of filth and the mussel shell of infidelity being familiar to the people of his time. His art—his interior world—was in keeping with an era of violence, disorder, pestilence, and pessimism.

As one enters the private worlds of the mind—what Professor Peter Heidtman of Ohio University once referred to as “the metaphorically vast inner region”—one may become a somewhat lonely explorer. One may even become, as one critic has said of Loren Eiseley, “a solitary fugitive from the 20th century,” from its worst manifestations, at any rate—the time pressures, the homogenization of culture, the hectic quality of existence, and the trivialization of so much of life. These facts of modern life contribute to the breakdown of loyalties, bonds, allegiances, and the sense of community essential to a civilized existence. Hence the desire on the part of many thoughtful people for a measure of isolation, or at least quiet.

For most people, our private worlds do not constitute a place to hole up; they are instead a kind of bounty provided by our mental existence. They are enriching and proof of the spaciousness of our total being. They represent what Eiseley called the “enormous extension of vision of which life is capable.” Our dreams enable us to project our innermost concerns and attitudes into half-factual, half-fictional worlds, composites that provide clues to our deepest feelings and intuition. We learn from these private worlds, from these mental constructions and remembrances of the complexity of existence and of the extraordinarily numerous points of reference in life. We hear voices and imagine situations that we would not heed or come across in the workaday world of nonimaginative contacts.

To be sure, the private world of the mind can overtake consciousness so that there is a serious disconnection with the real world. Such is the world of the psychotic or near-psychotic individual. Others, who are almost overwhelmed by private worlds of the mind, may continue to live in a normal community but may experience visions and fears that gravely impair their lives. The autistic child lives in such a private world, a world sealed off from the real one; he has great difficulty breaking out of it and communicating or showing affection.

Whether there is a subterranean domain of ancestral memories that we draw on in our private worlds is a question that has engaged great thinkers for many years. The work of Carl Jung deals with what he describes as the archetypes of a collective unconscious. And Dr. Alexis Carrel, the great medical scientist, wrote in Man, The Unknown in 1935 that certain activities of consciousness seem to travel over space and time. He said that man is not wholly comprised of the physical continuum, noting that “clairvoyants may detect hidden things at great distance. Some of them perceive events which have already happened or which will take place in the future.”

For my part, I believe there is a ghostly kingdom of the mind that we are in contact with but cannot truly comprehend. The human mind seems to be full of echoes of sounds made long ago, scenes that are beyond the limits of our travel or reading. The concoctions of the brain sometimes seem to be based on experiences that are completely beyond memory or artful construction, as though we had tapped an ancient reservoir of vision and feeling. Have they surfaced from some unknown past? The question must occur to many people. Experiences we do not recognize seem to speak to us from afar. I have often wondered whether I hear the voices of ancestors calling out to me when I respond to a situation in a particular way, a way that seems to have been ordained long ago. This is all a part of a mystery that we shan’t unravel, the enigma of the potential existence, of the human mind. These archetypes ought not to be seen as a dark or sinister side of the brain, but rather as thrilling evidence of the way our ordinary real-life world is enhanced.

As we ponder the existence and proliferation of these private worlds, we are compelled to ask: what drives human beings? How many of our choices and actions are decided by these other worlds inside us, the worlds apart from reasoned consideration of decisions? Rosaline Shevach Diamant observed in the May 1988 Atlantic that “human beings are the only species that can elaborate mental processes called fantasies into the intricate mental structures that enable us to organize our lives.” A danger that we sometimes face is that what we regard as pragmatic decision-making has its roots in fantasy, in the private worlds of the mind that should remain private and apart from our real-world existence.

The past, therefore, has never really been abolished, and we may even have openings into the future through our explorations of these private worlds—private worlds that enrich our lives by adding to the wonder of human existence.

Leave a Reply