The West should consider how to address Russia’s need for security guarantees to end the war in Ukraine, French President Emmanuel Macron said in an interview on Dec. 3.

“This means that one of the essential points we must address – as President (Vladimir) Putin has always said – is the fear that NATO comes right up to its doors and the deployment of weapons that could threaten Russia,” Macron said.

Macron’s statement made sense: Russia’s apprehension about NATO reaching its vulnerable southwestern border is at the very heart of the war, which could have been avoided had the United States agreed to Ukraine’s becoming a neutral buffer between the Western alliance and the Russian Federation.

Nevertheless, Macron’s statement has drawn a chorus of criticism from those who believe that Russia can and should be defeated and that no diplomatic concessions of any kind should be offered to Moscow. Last May, Macron was also criticized for saying that Russia should not be humiliated—so that when the fighting stops, a diplomatic solution can be found.

Of greater immediate import for the war was a meeting of European Union finance and economy ministers in Brussels on Dec. 6, when Hungary blocked the EU’s loan package, worth €18 billion ($19 billion), for Ukraine. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán insisted that “there is no veto, no blackmail,” but the move is widely seen as part of an attempt by the government in Budapest to unfreeze €7.5 billion of Cohesion Fund payments and €5.8 billion of the Recovery and Resilience Fund, which have been blocked because of Hungary’s alleged violations of the rule of law and its failure to tackle corruption.

The dispute reflects preexisting differences between Orbán and some of his partners over support for Ukraine. Since 2018, Hungary has been blocking ministerial-level political meetings between NATO and Ukraine in protest over Kiev’s violations of ethnic minority rights, specifically the limiting of their right to be educated in their native language. In addition, the State Language Law makes the use of the Ukrainian language compulsory in all spheres of public life. While Russian speakers were the main target of such discriminatory legislation, hundreds of thousands of Hungarians, Poles, Greeks, and others have suffered collateral damage from the law’s strictures.

Hungary’s position on the war itself was summarized by Orbán last July: the Western focus “should not be on winning the war but on negotiating peace and making a good peace offer.” The task of the European Union is not to stand alongside either the Russians or the Ukrainians, he went on, but to stand between Russia and Ukraine. “Sanctions and arms deliveries won’t lead to results,” Orbán reiterated in August. “When one rushes to put out a fire one doesn’t bring along a flamethrower.”

Such views are considered heretical by the dominant political establishment in Europe. Daniel Freund, a German Green Member of the European Parliament, said that the Hungarian veto of the EU loan package for Ukraine represented a “full escalation” by Orbán and called for EU funds to Hungary to be cut off. Valdis Dombrovskis, the European Commission executive vice president, said that the first payment to Ukraine will be made next month one way or another.

If Hungary does not secure support for its recovery plan in the EU Council before the end of the year, the country risks losing 70 percent of its share of funds. This is unlikely to happen, however, because Germany will be reluctant to go that far in antagonizing an important economic partner. Hungary and the other three countries in the Visegrád Group (Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia) provide one of Germany’s main export markets and manufacturing hubs in Europe.

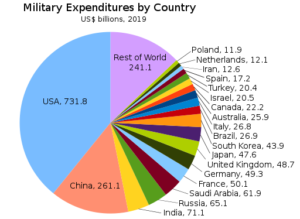

Germany also has an additional motive to appease Orbán and thus swiftly secure the aid package for Ukraine. That motive is to avert displeasure in Washington for Germany’s continued failure to reach the long-overdue 2 percent of GDP spending on defense. Government spokesman Steffen Hebestreit announced on Dec. 5 that the defense budget inaugurated after Feb. 24 would be downsized and that the 2-percent target will be missed in 2022 and probably in 2023 as well. Germany is “determined to come as close to the two-percent target as possible with the options we have,” Hebestreit said, and to reach the 2-percent target “in this legislative period,” which means some time in 2024-25. With the German economy in crisis and unlikely to improve in the years to come, this promise is near-certain not to be honored.

While the energy crisis continues to cripple Europe’s economies, the EU, the G7, and Australia announced on Dec. 3 that they were imposing a $60 per barrel price cap on Russian oil. The cap is supposed to be enforced by making it illegal for Western insurance companies to provide insurance to tankers transporting Russian oil if it was sold for more than $60 per barrel, which is about $25 below current global prices.

In response to the price-cap maneuver, Moscow has announced immediately that it will not sell oil below the market price. Meanwhile, China and India, Russia’s main customers, are simply ignoring the price cap. They are likely to develop new insurance arrangements that will only further erode Western dominance over the global maritime industry. An oil ministry official has said that the sanctions on Russian oil won’t apply to India because Delhi intends to use non-Western services to transport seaborne Russian crude oil to India.

In the coming months, the market price will stay well above $60 per barrel; Russia will refuse to sell its oil to the countries supporting the price cap, and the EU will be forced to get it from other sources, likely at much higher prices. With the Saudis backing Russia at OPEC+ and refusing to increase production, there may be oil shortages and increased inflationary pressures within the EU. The imposition of the oil price cap is yet another measure adopted by the EU that will harm its member countries more than it will harm Russia. By enforcing sanctions that have had minimal effect on their target, the Europeans are continuing to destroy their own economies.

The issue of when and how to press Ukraine to end the war may be creating some differences of opinion within the Biden administration as well. General Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has expressed doubts about whether Ukraine can regain control of the territories it lost after Feb. 24. “The probability of a Ukrainian military victory defined as kicking the Russians out of all of Ukraine to include what they define or what the claim is Crimea, the probability of that happening anytime soon is not high, militarily,” Milley said on Nov. 16. In the same vein, on Dec. 6, he said that the time was drawing closer for potential peace talks.

National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan is said to favor a deal with Moscow, which would not necessarily entail the return of all Russian-controlled territory to Kiev’s authority. Last month, Sullivan readily admitted that the U.S. was maintaining direct channels of communication with senior Russian officials.

The importance of maintaining direct channels of communication with Moscow became evident last month, when the Kiev regime obstinately rejected evidence that a missile that landed in eastern Poland and killed two men was not fired by Russia but by Ukrainian air defense. Zelensky effectively called for an all-out escalation by describing the incident as a “Russian attack on collective security in the Euro-Atlantic.” Not even the uber-hawkish government in Warsaw endorsed Zelensky’s patently false claim.

The Beltway Swamp, nevertheless, remains solidly bellicose, with the White House asking Congress for an additional $38 billion in aid for Ukraine. The military component of this package would more than double the entire U.S. expenditure since the conflict began ten months ago. More significantly, in October, the Senate Armed Services Committee submitted its amended draft of the National Defense Authorization Act for 2023, which would establish an “emergency” multiyear plan to award massive contracts to Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, BAE Systems, and others to manufacture weapons for Ukraine and to “replenish” U.S. stockpiles and those of “foreign allies and partners.” An amendment to the bill would allow the Pentagon to award noncompetitive no-bid contracts to arms manufacturers.

via Wikimedia Commons)

It can be predicted with near certainty that—faced with the prospect of endless billions in noncompetitive no-bid contracts—the military-industrial-congressional complex will prevail over Macron’s common sense, Orbán’s misgivings, Milley’s realism, and the American interest. That complex will be more than pleased to continue fighting Russia to the last Ukrainian militarily and to the last European economically.

Leave a Reply