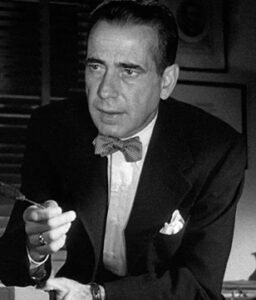

Blonde

Directed and written by Andrew Dominik ◆ Adapted from a novel by Joyce Carole Oates ◆ Produced and distributed by Netflix

The Enforcer (1951)

Directed by Bretaigne Windust and Raoul Walsh ◆ Written by Martin Rackin ◆ Produced by Milton Sperling ◆ Distributed by United States Pictures

Americans have a long romance with blondes. Think of Blondie and Dagwood, Janet Leigh, Meg Ryan, Cate Blanchett, Michelle Pfeiffer, Margot Robbie, Charlize Theron. The one that stands out from the crowd is, of course, Marilyn Monroe, the blondest of them all and apparently well aware of this simple and highly profitable truth.

The first thing to ask about Joyce Carol Oates’s biographical novel, Blonde, is why Oates decided to explore the life of Monroe in her book and then participate, however passingly, in the making of the film. Hadn’t Monroe’s reputation suffered enough before she died in 1962? Did we need to rehash the supposed sexual relationship between our Harvard-bred president, John F. Kennedy, and our homegrown blonde bombshell? I, for one, have had quite enough of the Monroe scandal juggernaut through the years and am quite willing to decline any further delving into this tawdry enterprise.

I can’t be sure, but I suspect Oates has it in for the Kennedys. For evidence, I submit her novella Black Water, in which Oates depicted what happened when Ted Kennedy had his driving accident, fatal to his passenger Mary Jo Kopechne, on Chappaquiddick Island in 1969. This book, too, became a film, Chappaquiddick, which I reviewed in these pages in 2017.

When Ted’s little accident happened, I was teaching at Bishop Loughlin Memorial High School in Brooklyn, and I recall with embarrassment that the more sentimental Irish brothers with whom I taught morosely referred to the incident as a witch hunt. There was no shaking them from their inexcusable Irish allegiance to what some commentators have laughably called America’s “royalty.”

But getting back to Monroe, there’s no question that Blonde, both book and film, is a profitable product. There was and continues to be money to be made from Monroe’s notoriety. More than anything else, she was a moneymaker—and still is, as she continues to fascinate the public 60 years after her death.

Certainly, Monroe’s beauty is indelible and mysterious, though as an adolescent, I couldn’t totally understand her appeal. Yes, she was beautiful, sexy, and famously (or infamously) willing to pose nude. But Monroe’s screen acting was almost always over the top—as with everything she did: it was too much.

In 1956, for instance, she starred in director Joshua Logan’s Bus Stop as a down-on-her-luck cafe singer pursued by an unbelievably celibate multimillionaire Montana rancher, played by Don Murray. The resulting film isn’t very good, but it has its share of comedy. Monroe does a merely passable job as the young woman and Murray better than okay as the befuddled rancher, a man both besotted with and wary of the young woman to whom he finds himself attracted, despite his unwillingness to kiss her.

Monroe’s performances as an actress are, generally speaking, less than stellar. She seems uncertain what to do with her characters, and the audience often finds her staring into the middle distance as her more skilled costars step carefully around her. One gets the sense that Robert Mitchum and Laurence Olivier feared they might break this vulnerable creature in their pairings with Monroe: River of No Return (1954) and The Prince and the Showgirl (1957), respectively.

By the 1950s, Monroe had been cleverly packaged by the film studios and managed by the likes of the entrepreneurial Hugh Hefner, that courtly admirer of the female form who put her nude photo in his first issue of Playboy magazine. He only paid her all of $50 for posing, but it certainly paid off for her career.

The question that Oates raises but never adequately answers is why Monroe allowed herself to be shaped by people who had little interest in her personal welfare. She seems to have been largely unaware of how her talents were affecting the public. She could sing a bit, and, of course, spectators couldn’t miss her physical beauty. Literary stars such as Norman Mailer and Arthur Miller found her irresistible and put her in their copy. But she was vulnerable to exploitation and ultimately used and abused by those dashing lover boys, Jack and Robert Kennedy. If Oates has it right in Blonde, Monroe allowed herself to be handed over to the Kennedys, who took full advantage of their power to enjoy what she had on offer.

Needless to say, the Kennedys’ behavior was disgusting. How I dislike them, beginning with their father, Joe, who advised his sons to sleep with as many women as they could manage. It’s not their politics alone that troubles me. They disgraced the Irish reputation.

In Blonde, the Cuban actress portraying Monroe, Ana de Armas, does so quite convincingly. She’s shown in one scene talking to her fetus during an abortion she’s undergoing, ostensibly at the behest of her studio bosses, although the truth of this story is not at all certain. We watch as she changes her mind and tries to cancel the procedure at the last minute. She bounds from the gurney wheeling her to the operating room and runs naked through the hospital’s hallways. One way to put it is that in playing the role, de Armas seems to have been abused in much the same manner as Monroe had been.

In the final analysis, Blonde plays fast and loose with the facts of Monroe’s life to create another lurid and sleazy film that fits into a certain genre of successful storytelling. Remember that Émile Zola did splendidly with his 1880 novel Nana, which was about a prostitute who became the darling of Paris. Zola told a story that’s pretty much the same as the one Oates tells about Monroe, though Monroe stops short of being an actual, practicing whore. As Blonde tells it, in one of her adventures, Monroe slept with the sons of Edgar G. Robinson and Charlie Chaplin. Titillating gossip from the Silver Screen era, to be sure, but there doesn’t seem to be any evidence that this is actually true. It does, however, add some profitable spice to the proceedings.

There’s another scene in which the actor Bobby Cannivale, playing Joe Dimaggio, beats up Monroe, after their remarriage, for displaying her wares in that famous shot from the 1955 film The Seven Year Itch, in which a blast of air from a subway grate blew her white dress over her head.

One wonders with what faculty the baseball great could have been thinking. It must surely have been another body part than his brain. This, of course, was after the baseball star had foolishly left his wife and family and found himself yoked to this poor, much-damaged show girl.

All in all, the story is a very sad one. The film shows Monroe’s descent into abuse beginning with her alcoholic mother battering and almost drowning her when she was about three years old. But did such an event actually ever take place? One has to wonder. It seems to me that most of us have learned with good reason to distrust whatever Hollywood tells us.

Of course, we all know it’s likely that Monroe tragically committed suicide a few days after John F. Kennedy’s assassination, on Nov. 22, 1963, but as for the rest of the Kennedy connection, it’s conjectural at best. If only Monroe hadn’t sung “Happy Birthday” to Jack Kennedy on the occasion of his 45th birthday in 1962. There she wore a beaded glistening dress which today is valued by auctioneers at about $5 million, or so we were told when modern glamour queen Kim Kardashian wore it at the Met Gala last year.

A further caution about Blonde: The film has chosen to have de Armas spend quite a lot of time running about in her altogether. I can report that she’s quite beautiful, but her nakedness, though muted by black-and-white filming, might not be to everyone’s liking, excepting, of course, the swinish male audience on whom filmmakers typically rely for a sizable amount of their profits. And I’m not excluding myself—not entirely, anyway. I didn’t avert my eyes from the spectacle. I would plead this was a matter of professional duty, but that excuse would risk being mocked by my readers.

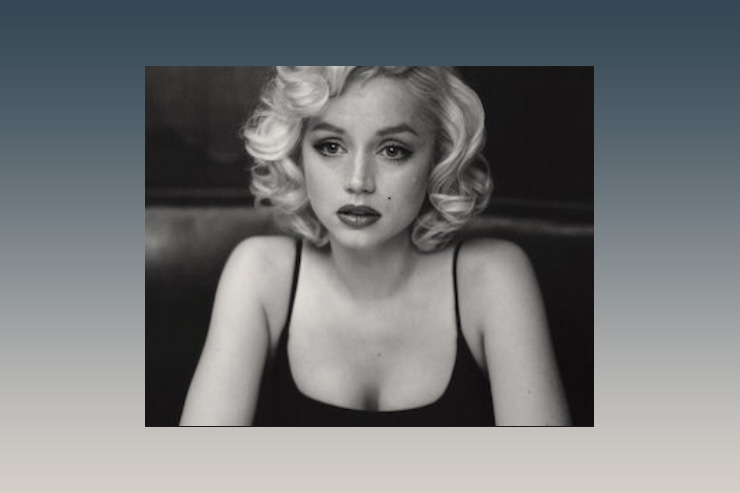

The Enforcer

(United States Pictures)

Let us now turn to something less lurid: a hardboiled crime story from the 1950s. I revisited The Enforcer, a fairly ordinary police procedural starring Humphrey Bogart, directed in part by one of his favorite and most frequent collaborators, Raoul Walsh. This plain and unassuming crime tale won critics’ favor and is still highly regarded. It boasts some good character acting from Ted de Corsia, Zero Mostel, Everett Sloane, and Bob Steele, who work together to tell the story of Bogart’s district attorney consumed with his mission to bring the head of Murder Incorporated to justice.

The plot unfolds clumsily and with little suspense, except for what some crisp black-and-white cinematography contributes to the film’s visual display. It also benefits from a good deal of humor provided by a sniveling lowlife criminal informant played by the invaluable Mostel. The actors play their parts well, and the plot delivers justice done, as it ought to be.

All in all, the film is nothing special, but it makes an enjoyable two hours in the theater or on television, and an instructive contrast to what’s on offer today. Despite dealing with criminal subjects, it focuses on the good guy and his quest for justice rather than on dwelling in the gutter and making heroes of villains. It’s an example of the quality of an average, journeymen film from the supposedly drab 1950s, enlivened with a touch of film noir and documentary-style realism. It certainly beats the fantastical and lurid entertainments that populate movie houses in our time.

Leave a Reply